Making Information Make Sense

InfoMatters

Category: Information / Topics: History • Information • Statistics • Trends

COVID-19 Perspectives for November 2021

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: December 337, 2021

Europe takes the brunt of the latest surge, just as Omicron, another potentially dangerous variant, arrives to dampen the holiday season…

Putting the COVID-19 pandemic in perspective (Number 17)

This monthly report was spawned by my interest in making sense of numbers that are often misinterpreted in the media or overwhelming in detail (some would say that these reports are too detailed, but I am trying to give you a picture of how the COVID pandemic in the United States compares with the rest of the world, to give you a sense of perspective).

These reports will continue as long as the pandemic persists around the world.

Report Sections:

• November-at-a-glance

• The Continental View • USA Compared with Other Countries

• COVID Deaths Compared to the Leading Causes of Death in the U.S.

• U.S. COVID Cases versus Vaccinations

• Profile of Monitored Continents & Countries • Scope of This Report

November-at-a-glance

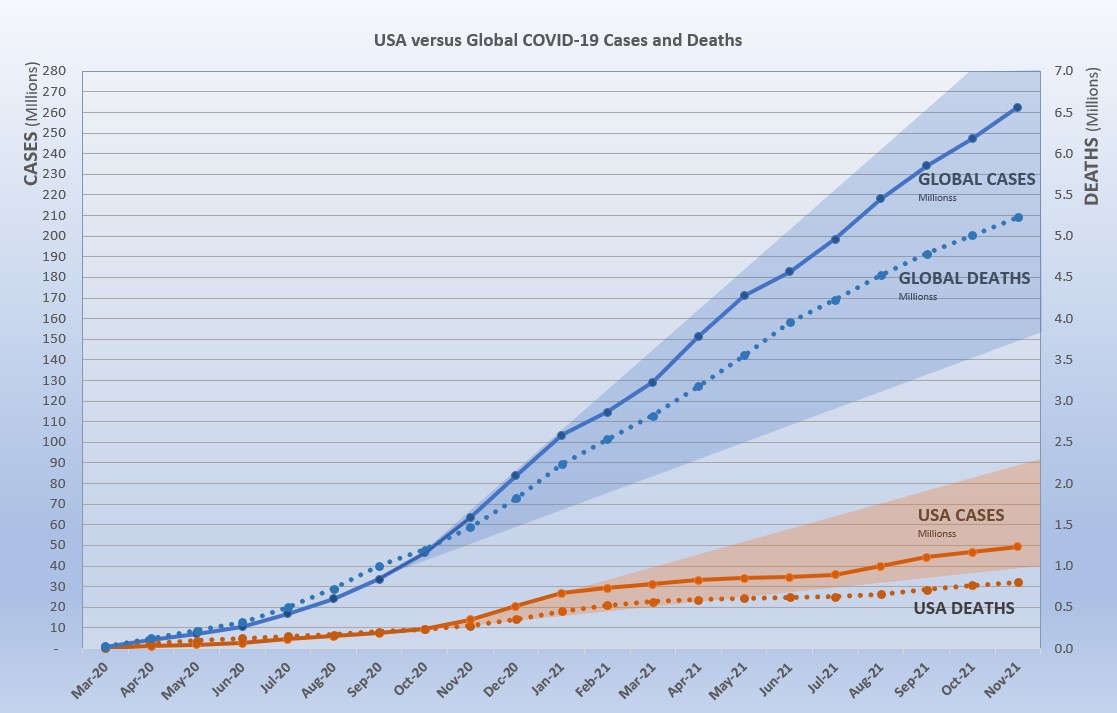

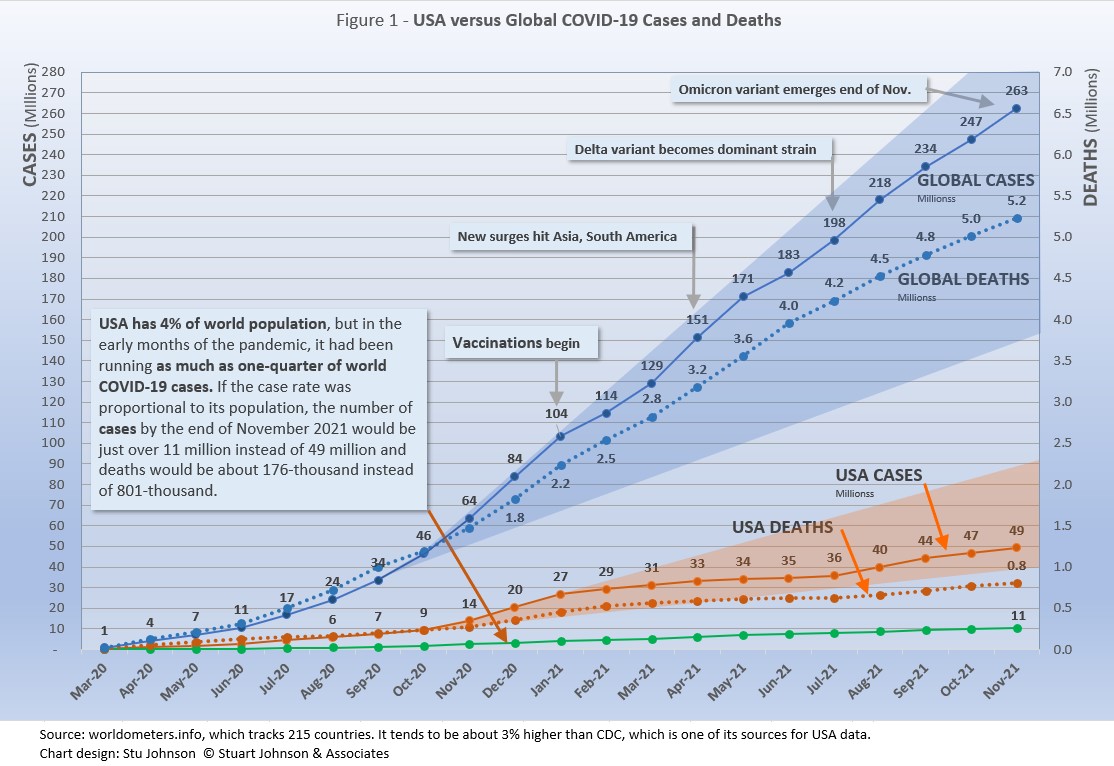

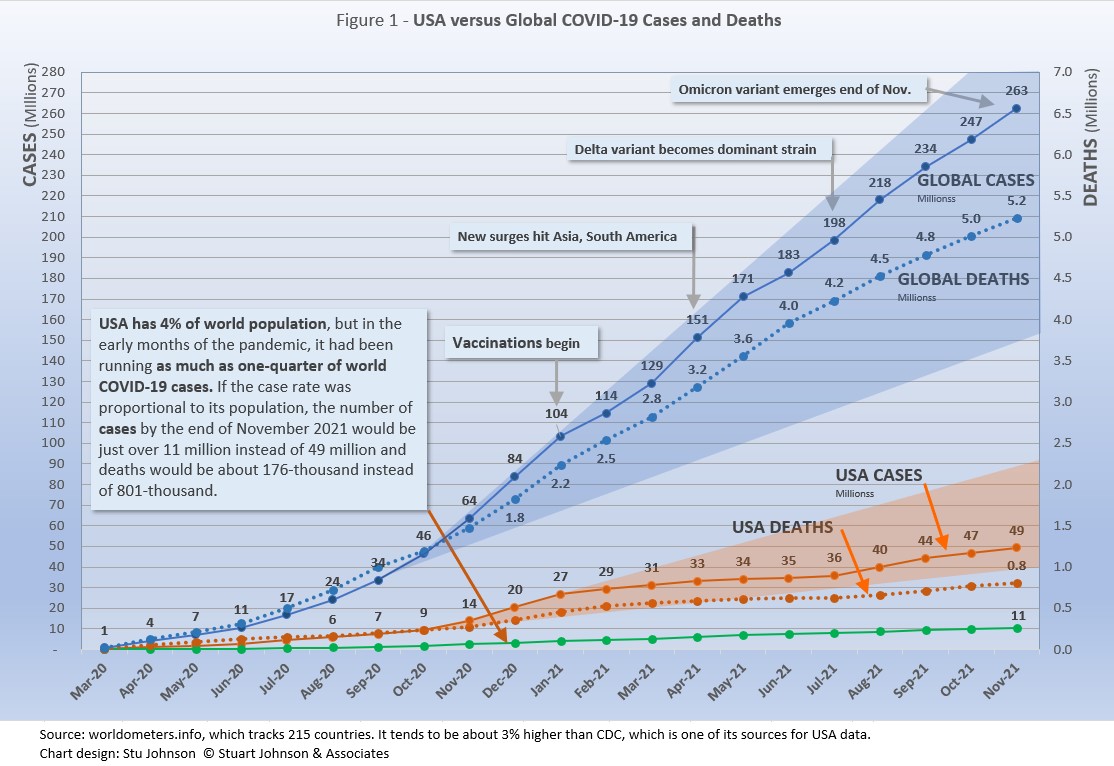

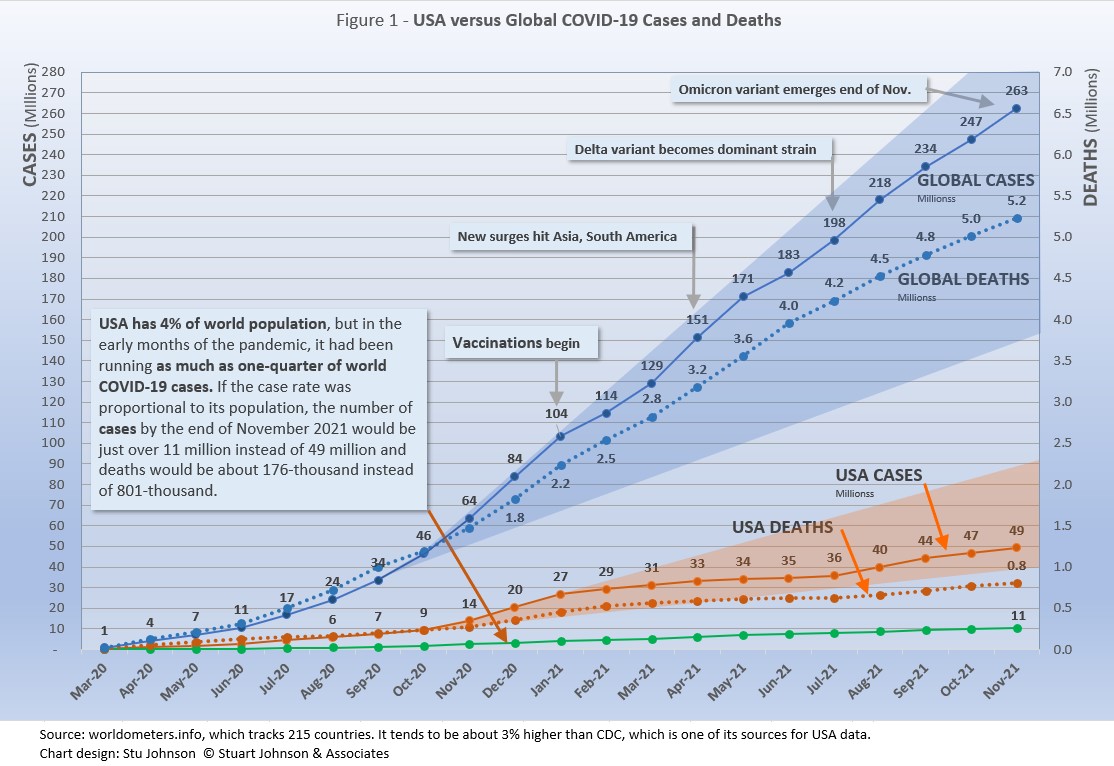

- COVID-19 continued to spread around the world, reaching 263-million cases by the end of November, up 6% from October. Deaths from COVID around the world rose to 5.2-million, up 4% after crossing the 5-million mark in October.

The level of reported cases represents 3.3% of the global population of 7.9-billion, up from 3.1% at the end of October. The increase over October remained steady, at 6%, back to the level of May following an apparent delta-related surge, when the monthly increase went up to 10% in August. That means that so far the delta-related surge was not as significant as previous surges (November 2020-January 2021 and April-May 2021), but continues to be problematic. In some areas it is driven by dense populations and/or lack of vaccine, in others (USA being a prime example) by vaccine resistance as evidenced by reports that hospital admissions for COVID are nearly all among those who have not been vaccinated. Adding concern as the month closed was the identification of the omicron variant by South African researchers. More on this below.

The blue "cone" in Figure 1 shows the possible high and low projection of global cases, with the bottom (roughly 150-million) representing the trajectory of the lower pace in late summer 2020 and the upper (approximately 300-million) representing a continuation of the surge from November 2020 through January 2021. You can see that the curve for global cases has bent down and back up several times since February 2021, but is very slowly moving away from—but still close to—the upper edge of the prediction cone. USA had fared better until August, which I'll get to below. - The pattern for deaths tends to lag behind cases by weeks or months, and the global rate of increase continues to fall below that of cases—dropping from a 23% increase in January to 4% at the end of November, with a modest increase to 7% in July and August. While the curve for deaths is not increasing as much as that for cases, it is still climbing at a noticeable rate (unlike USA where cases and deaths flattened between January and July 2021, before rising again).

- Where South America was clearly going the wrong way through early summer, things have significantly reversed. Headed toward eclipsing Europe (the trouble spot in November) in the number of cases and deaths, the curves began to turn down in July and flatten through November.

South America has also taken the lead in vaccination doses, surpassing Europe and North America in August. Ironically, while the continent is improving several South American countries remain as trouble spots. See more in The Continental View.

- USA. continues to lead the world in the number of reported cases and deaths, but also leads the world in the number of COVID tests and is respectable in vaccinations, but hampered by vaccine resistance.

While the 18.8% USA share of global cases at the end of November was down from a high of 25.9% in January, the trend is erratic. The rate was 18.9% in June before dropping to 18.0% in July, then headed back up to 18.9% in September and October.

Similarly, deaths have declined from 20.9% of the world total in September 2020 to 14.5% at the end of August 2021 before heading back up to 15.5% at the end of November. As you will see in details to follow, while USA outpaced everyone through the early months of the pandemic, the vast disparity was slowly shrinking until the delta variant brought a resurgence in cases.

The projection cone surrounding USA Cases in Figure 1 shows a pronounced flattening of the curve from January to July (vaccinations), with a very noticeable upward bend in August (delta variant among unvaccinated)—though still in the bottom half of the projection cone (which for USA extends from roughly 40- to 90-million). The upward bend for USA cases from August to November is clearly visible in Figure 1, but even more pronounced in Figure 10 below, which "zooms in" on USA.

Figure 1 also shows how much lower cases in the US would be—approaching 11-million by now, instead of 49.3-million—if they were proportional to the global population. It would also mean about 176-thousand deaths instead of 801-thousand.

- The omicron variant represents a new potential threat to spreading and prolonging the COVID pandemic. Yet, it is early. While the delta variant has been a factor, its impact has been uneven globally and its extent less than the massive surge felt globally between November 2020 and January 2021. We will not know the true nature and potential impact of omicron for weeks as researchers dig deeper. For a good overview of this process, see "We won't know how bad omicron is for another month" by Antonio Regalado, reported in the MIT Technology Review.

- Countries to watch. No countries have been added to the list of countries I monitor. The weekly comparison report on worldometers, however, gives a sense of hot spots to watch. Based on activity in the last week or two, this includes Czechia, Vietnam, Hungary, Austria, Slovakia, Switzerland, and Greece. While some of these have population too small to make much of an impact on this report, they generally confirm (along with countries recently added to my monitored list) that the shift toward southeast Asia and the Middle East in the past several months has shifted to renewed surges in Europe, which are casting a pale on the holiday season.

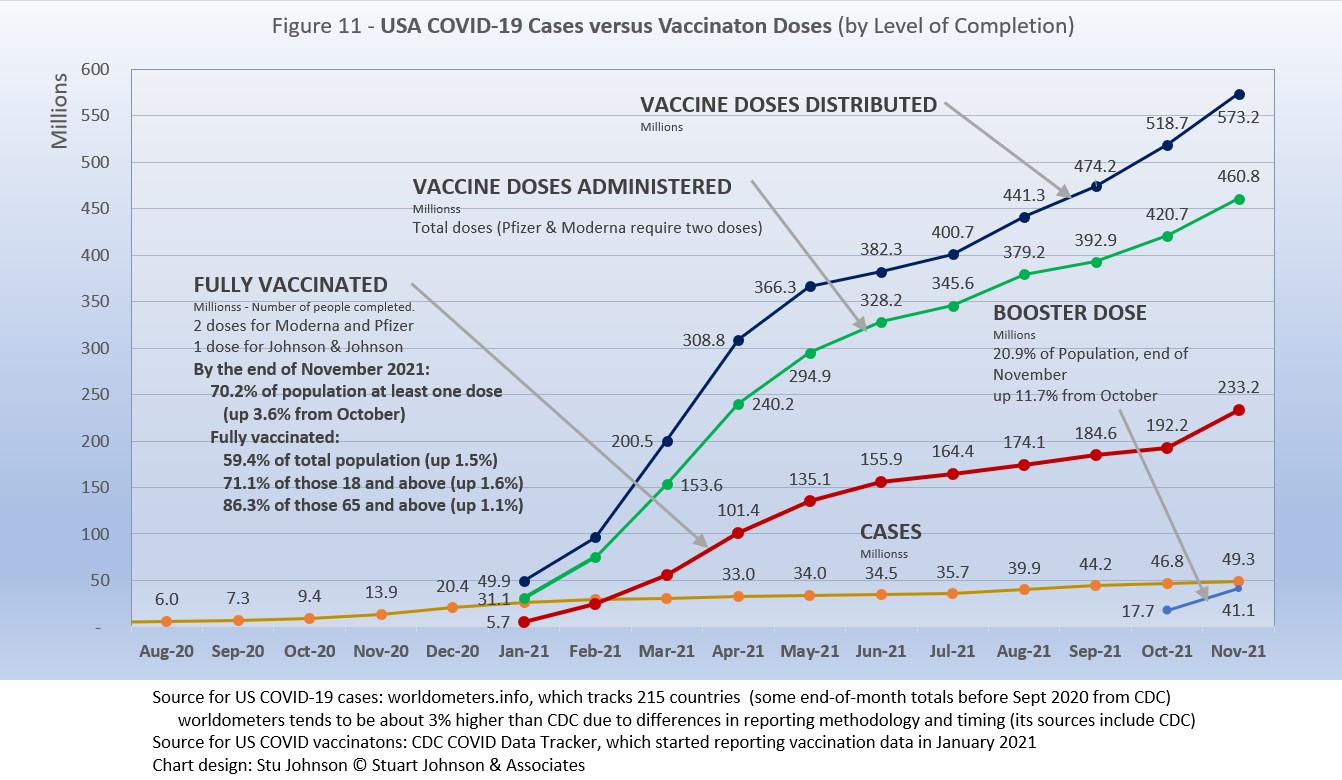

- With vaccinations, USA continues to move ahead. After a noticeable slowdown in June and July, total doses distributed climbed to more than 573-million by November. The curve for doses administered ("shots in the arm") picked up after a slight slowdown in September. Meanwhile, the curve for those fully vaccinated rose noticeably in November, to 231-million, up 3.6% from October (See Figure 11).

Where you get information on COVID is important. In an atmosphere wary of misinformation, "news-by-anecdote" from otherwise trusted sources can itself be a form of misinformation. As I go through the statistics each month, I am reminded often that the numbers do not always line up with the impressions from the news. With that caveat, let's dig into the numbers for November 2021.

The Continental View

The most obvious change in November is the surge in COVID cases in Europe. The other major continents either continued at their recent pace or slowed somewhat in growth of cases. Oceana is not included because of its small size, about one-half a percent of world population.

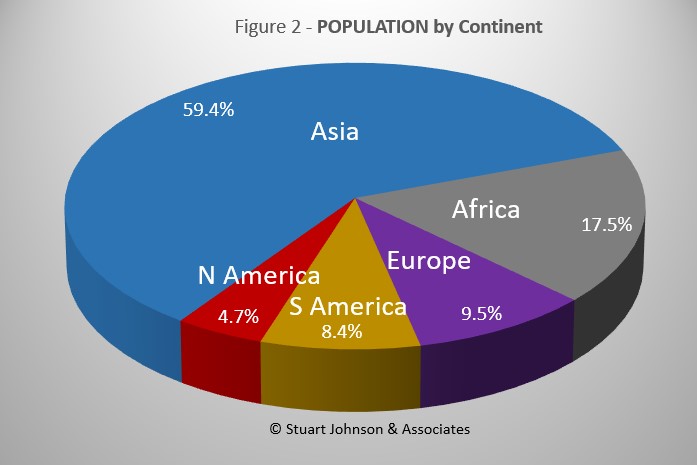

While COVID-19 has been classified as a global pandemic, it is not distributed evenly around the world.

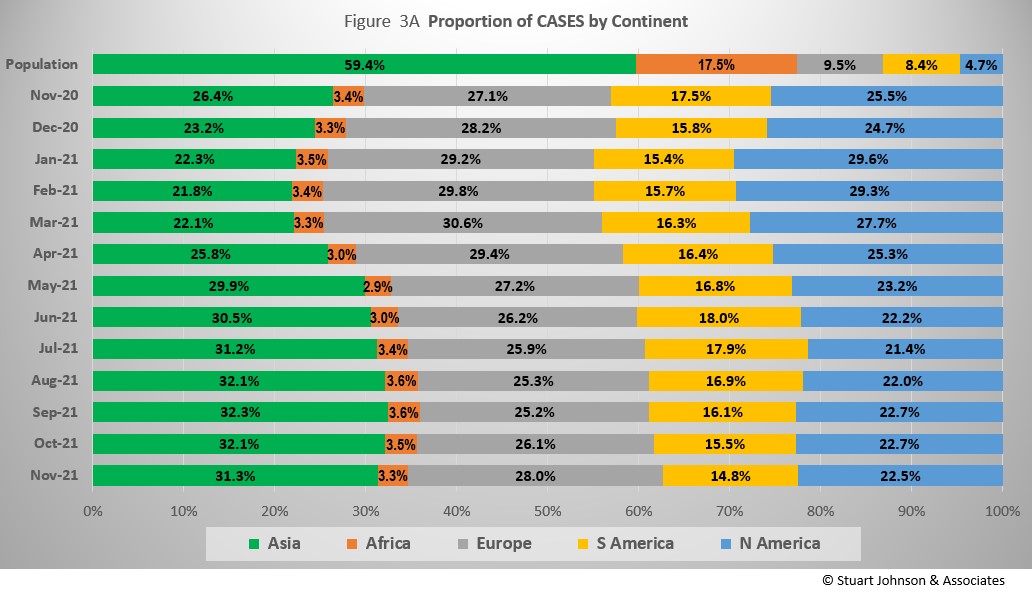

Asia accounts for 59.4% of the world's population (Figure 2), but had only 31.3% of COVID cases at the end of November (Figure 3A)—affecting a mere 1.7% of its population—down from a high of 32.3% in September. (COVID cases now represent 3.3% of world population).

The biggest trends in the proportion of cases among continents are most noticeable since March:

- Asia - rising to a peak of just over 32% in September, then declining slowly the last two months

- Europe - falling through September from a high of nearly 31% in March, with a bump up to 26% in October and a sharper surge to 28% in November

- North America - falling through July from a high of nearly 30% in January, then back up slightly, but remaining below 23%

- South America - after peaking at 18% in June, steadily descending to just under its low of 15% in November

- Africa - hovering around 3.5%

Where Asia and Africa combined represent about three-quarters (76.9%) of the world's 7.9-billion people, Europe, South America and North America still account for nearly two-thirds of COVID cases (65.3% - Figure 3A) and about 7 in 10 of COVID deaths (72.4% - Figure 4A). The shares for Europe and the Americas combined were slowly coming down from their highs (74.7% for cases and 80.8% for deaths in February), but have inched back up a fraction of a percent each month since September. Since South America has been declining overall, that increase is driven by Europe and North America.

While news reports continue to give the impression of widespread delta-variant surges, growth in the number of cases since July has not been uniform across continents. Asia and North America both showed an upturn in cases for August and September, but slowed in October and November. Europe, on the other hand, showed a more restrained increase in rate between July and September, with a slight acceleration in October, followed by a significant surge in November.

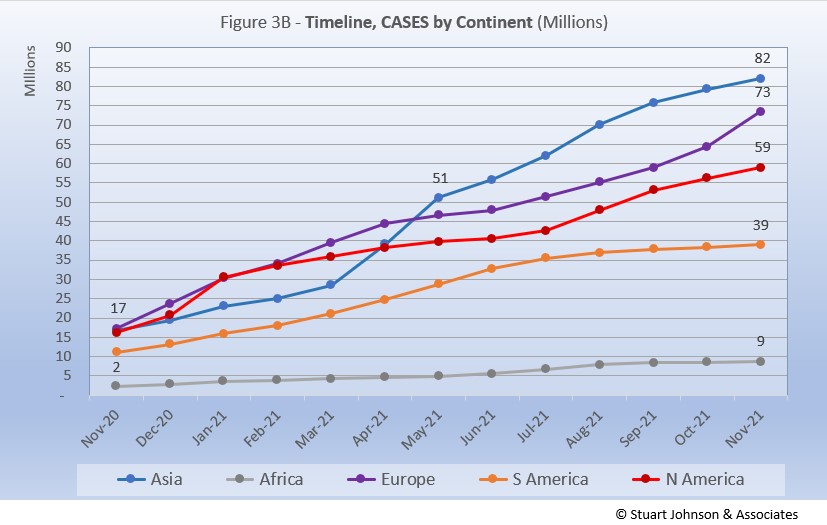

Meanwhile, South America actually started to level off in July, while Africa experienced a noticeable increase in cases from June through August before leveling off again, maintaining its unique position far below the other major continents in the raw number of cases.

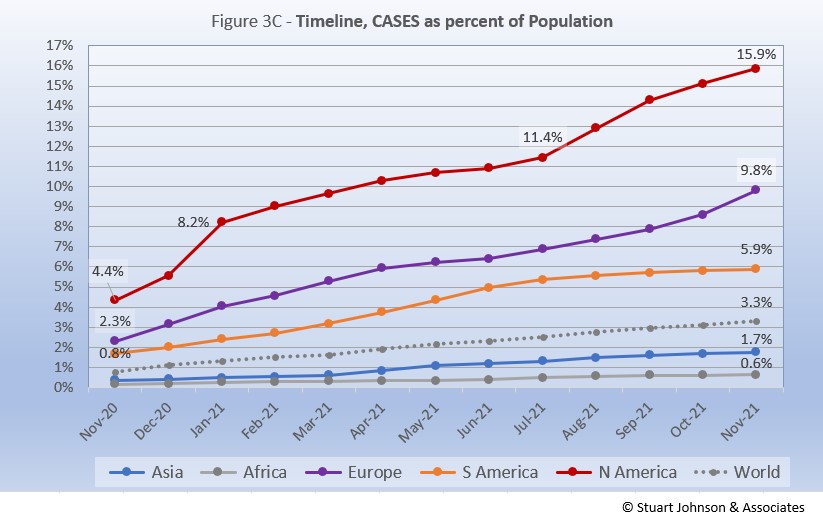

The raw numbers of Figure 3B can be deceptive. Figure 3C gives a more realistic picture of impact by translating raw case numbers to percentage of population. The shape of the curves is similar to those for raw numbers, but the order and spacing paints a different picture.

After a sharp increase in January, North America slowed down for six months, before jumping 1.5 points to 13.0% in August, continuing that pace into September before slowing slightly, ending November with COVID cases representing 15.9% of its population.

Europe remains well below North America, though its proportion of cases rose sharply from 7.9% in September to 9.8% in November. At the same time that Europe was trending upward, South America saw its curve flatten, rising only 0.5% since August, ending November at 5.9% of COVID cases in its population.

Asia and Africa, the two largest continents, remain at the bottom by proportion of COVID cases for their populations. Asia increased more noticeably than Africa between April and September, but both ended well below the global level of 3.3% at the end of November—Asia at 1.7% and Africa at 0.6%. In fact, it is the low proportions of Asia and Africa that have held the global curve to a nearly straight line progression. Omicron, the newest variant, first reported in South Africa at the end of November, could change that, with growing arguments over inequities in global vaccine distribution affecting the ongoing spread of COVID.

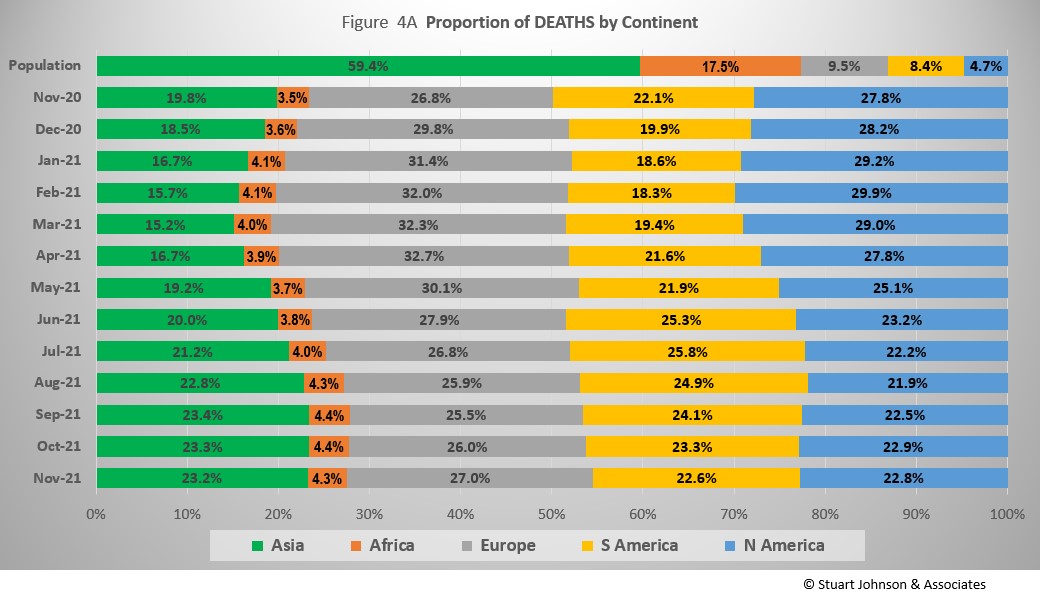

The proportion of deaths between continents is even more distorted than that of cases. In the early months of COVID, Europe and the Americas were growing in deaths, causing Asia to bottom out in its proportion of global deaths at 15.2% in March. The trends since then shadow those of cases, but lag behind by a month of two.

- Europe retains the highest proportion of COVID deaths at 26%, up a full percentage point in November, but down from its high of nearly 33% in April—still nearly three times its nearly 10-percent share of world population.

- Asia ended November just over 23% of world COVID deaths, down one-tenth of a percent each of the last three months, still well above its low just above 15% in March—and far below its 59% proportion of world population.

- South America and North America are nearly tied at slightly less than 23% at the end of November. South America is down from its high of nearly 26% in July, North America below its high of nearly 30% in February, but above its low of just under 22% in August. Like Europe, both are well above their proportion of world population (8% for South America, nearly 5% for North America).

- Africa has hovered around 4%, with the last four months pushing upward slightly, but far below its 17% share of world population.

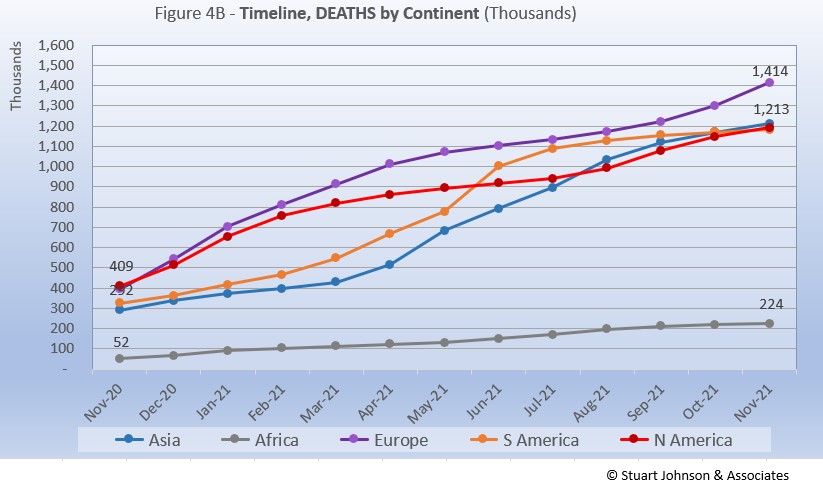

Deaths through October shows that while the trajectory lags behind cases and has progressed at a steadier rate, it does reflect the overall changes in Cases by continent. Except for Africa, which is well below the other continents in the number of COVID deaths, for the other four the 1-million milestone is history.

Europe remains at the top in number of deaths, at 1.4-million. South America was headed toward passing Europe back in the surge of early summer, then flattened, even as the delta variant was causing surges elsewhere. North America leveled off after vaccinations began in January, then started moving up again with the combination of vaccine resistance and the delta variant. Asia started to accelerate in May, on a path to join Europe, but started to slow in the last two months. The result of these wandering curves is that Asia and the Americas came even closer to convergence in November than we saw last month.

Meanwhile, Africa progressed at a fairly steady pace, well below the others both in level and rate of change, despite being second in size, with 1.3-billion people.

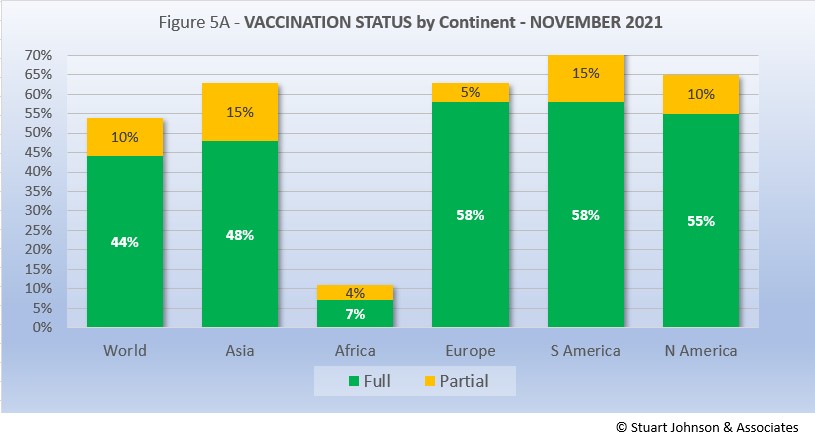

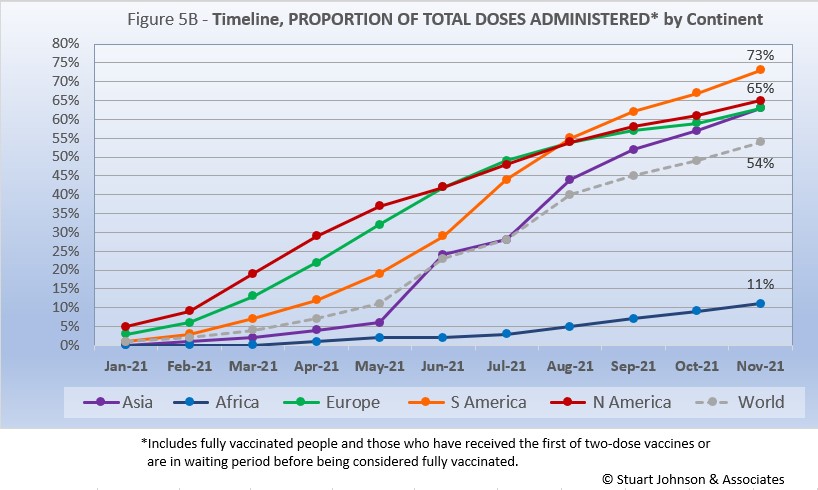

Vaccinations

As Figure 5A shows,more than four in ten of the global population has been reported as fully vaccinated (roughly 3.5 billion people), with another 10% having received the first of two doses or in the waiting period to be considered fully vaccinated. Given continuing gloomy reports in the news, those numbers may be surprisingly high given the monumental task of vaccinating multiple billions of people.

South America took the lead in total vaccinations in November (73%), but is tied with Europe for the proportion who are fully vaccinated (58%). North America comes next, putting the three smallest continents by population over the 50% threshold for full vaccinations. Asia follows with 63% partially vaccinated and just under half (48%) fully vaccinated. Africa remains far below, with 11% having had at least one dose.

While South America got into vaccinations later and slower than North America and Europe, Figure 5B shows how it pushed its way to the top of the total vaccination doses administered by August, expanding its lead since then—and this by proportion of population, not raw numbers, so it's a fair comparison. Where North America started aggressively, it slowed in June as Europe caught up, then began to move ahead slightly, ending November at 65% compared to Europe at 63%.

The world trajectory was clearly influenced by Asia, which showed serious vaccination administration starting in June, moving upward to nearly match Europe in October, then matching it in November at 63%. Africa remains far behind the others, though there is an encouraging upward movement beginning in July.

Because a majority of vaccines require two doses, we will likely see total doses expand more quickly in coming months, with full vaccination catching up at a rate dependent on supply, strategy and willingness of populations to cooperate.

Comparison of U.S. with other Countries

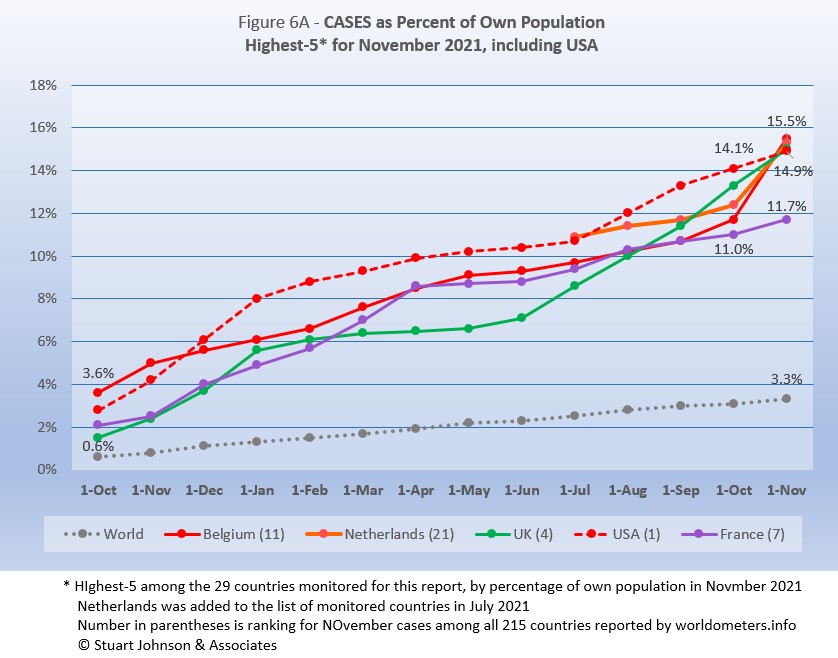

Cases

Raw numbers are virtually meaningless without relating them to the size of a given country, so looking at cases as a proportion of population helps get a sense of the relative impact.

France returns to the top-5 after being replaced by Argentina last month. The other four return, but shuffle their order significantly because of the surge of cases in Europe.

Over the 14 months shown in Figure

6A, the top-5 have crossed paths several times and ended October spread evenly, all well above the global level of 3.3%. Surges in Europe brought a remarkable ending to November, with Belgium, Netherlands, UK and USA all in a very tight cluster between 14.9% and 15.5%. Had USA surged like the other three, it would have been well ahead, but its more moderate gain moved it from number 1 the previous three months to number 4 in November. France, as well, showed a modest gain rather than the surge experienced by its neighbors, putting it in fifth place, a full three percent behind the others.

Another way to look at population proportion is the measure "1 in." The global figure of 3.3% means that 1 in 30 people in the world have been reported with COVID (and that only by official record keeping, not including any unreported and likely asymptomatic cases). For USA it remains 1 in

7. Netherlands and UK drop by one to also end November at 1 in 7. Belgium also drops a point, to 1 in 6. France stays at 1 in 9.

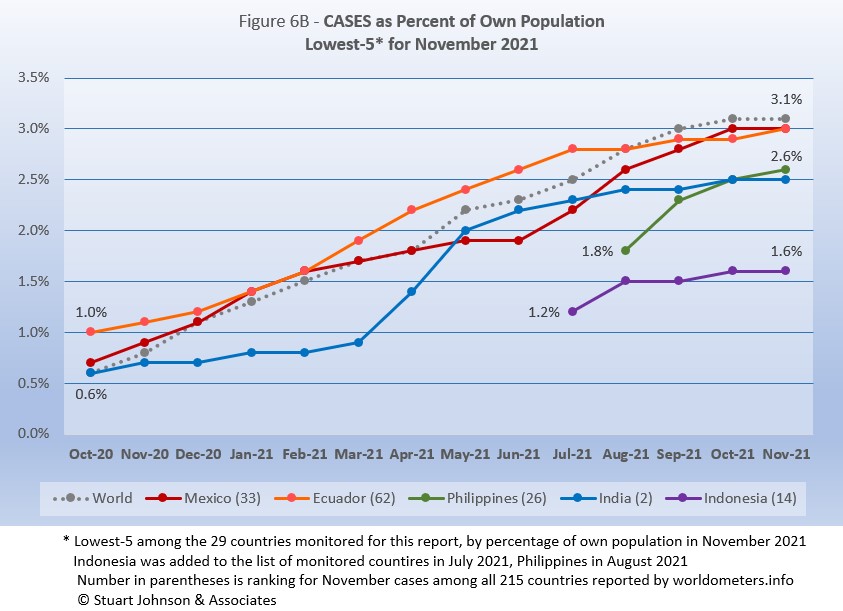

All five countries return from October, in the same order. All five have been at or below the global level since August.

Mexico and Ecuador criss-crossed last month, with Ecuador slowing and Mexico continuing on an accelerated path. In November, Mexico flattened its pace while Ecuador moved up, so both ended at 3.0%. Philippines, which was added to the list of monitored counties in August, moved upward, meeting India last month and moving ahead this month. India had a major surge in April and May, then slowed, with a bump in October not enough to keep it ahead of Philippines. As seen before, however, it is difficult to predict future direction from the small changes seen here. Indonesia, added to the list of monitored countries in July, remains the lowest of the 29 monitored countries by proportion of cases for its population and the only one still below 2%.

These countries represent a considerable spread in size, from India, the second largest country, to Ecuador, ranked number 67 of the 215 countries tracked by worldometers. For Ecuador, its 3.0% of population means that 1 in 34 have been reported as having had the COVID virus, for India it remains 1 in 40, and for Indonesia 1 in 64.

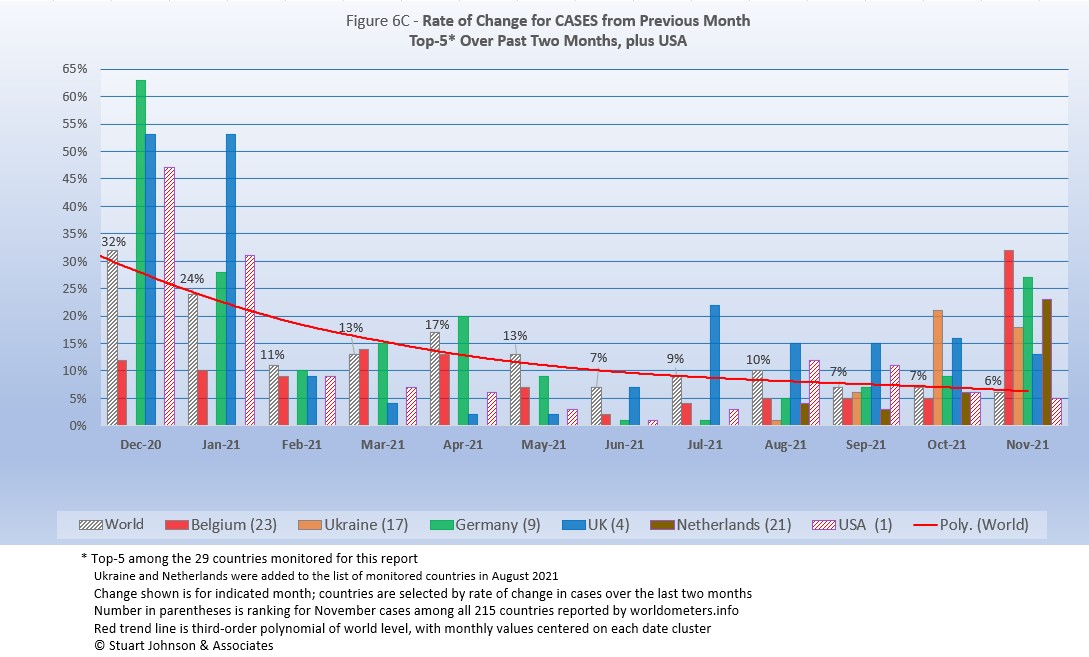

Because the size of countries makes the use of raw case numbers illusory, another measure I find helpful is the rate of change from month to month (Figure 6C). The focus of the selection is on recent changes, but the chart goes back to December 2020 to keep the surges of late 2020 in perspective.

For this chart, countries are selected based on the change over two-months (end of September to end of November for this report). Philippines and Turkey have been replaced by Belgium and Germany. USA, which appears in every report, remains below the top 5.

The overall trend (red line, reflecting global level) flattens as it drops, ending November at the low of 6%. (A polynomial trend line flexes as adjacent data points go up and down, so the leading edge of newest dates can change the shape of the curve as new months are added).

Overall, global levels were much higher from November 2020 through January 2021 (the highest period of surging cases as pointed out in Figure 1), as was the absolute variation between countries. Global levels remained over 10% through May, then has been at or below 10% since then.

Belgium has been below the global level of monthly change until its recent surge saw it increase 32% in November. Ukraine, added to the list of monitored countries in August, increased 18% in November, but its 21% in October put it in the top-5 of change over two months. Germany, not in the top-5 five even during previous surges, increased 27% in November. UK, like Ukraine, is in the top-5 because of significant increases in both October and November (16% and 13%). Netherlands, added to the list of monitored countries in August, saw a 23% increase in cases in November.

USA started well above the Global level from November 2020 (48%) through January 2021 (31%), then dropped to 9% in February after vaccinations had begun and the surge seemed to have ended (in USA anyway). From there it is fell further below the global level each month until reaching a low of 1% in June. This has reversed, with a small bump in July that was still well below the global level. Then August went above the global rate (10%) to hit a 12% increase, before declining each month, reaching a 5% increase in November, dipping back below the global level the last two months.

Deaths

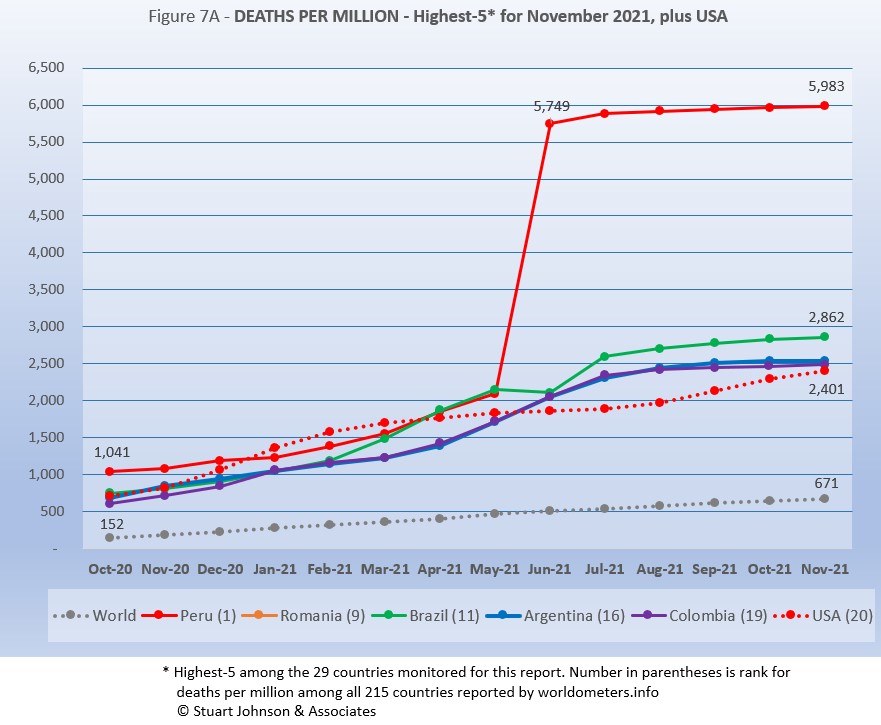

Because deaths as a percentage of population is such a small number, the "Deaths-per-Million" metric shown in Figure 7A provides a comparable measure.

Romania, added to the list of monitored countries in October, replaces USA (which remains in the chart because it is always included). The other four countries have all been in the top-5 since June.

As Figure 7A shows, Peru still soars over the others following a correction to its death data in June. November remains double #2 Romania and nearly 9 times the Global level of 671.

While the worst deaths-per-million is still dominated by South American countries, as suggested in other parts of the report there has been a slowing and even some flattening evident in the last four months. Peru,Argentina, and Colombia have all seen a flattening of the deaths-per-million curve (the number cannot go down, but growth can flatten). Argentina has slowed since July, but continues to grow at a noticeable pace.

USA rose steadily until evidence of the effectiveness of vaccination began to become evident with a slow down from March through July, before turning back upward in August, coinciding with the delta variant and vaccine resistance. USA is on a track to get back in the top-5 if it surpasses Argentina and Colombia next month.

Since this analysis focuses on 29 countries that have been in the top-20 of cases and deaths, there are 7 other countries not monitored with Deaths-per-Million between Peru, with a population of 33.5M, and Romania, with 19.1M. The largest are Bulgaria (6.9M, 4,152 Deaths-per-Million), Hungary (9.6M, 3.606), and Czechia (10.7M, 3,099).

All of the countries on the chart, including USA, are all well above the Global level, and (except for Peru) fairly close to each other for the past four months after nearly converging in June.

While the delta variant was causing cases to rise, particularly in July and August, death rates in general remained unaffected or low in comparison—even South America, which had been the exception, is slowing down.

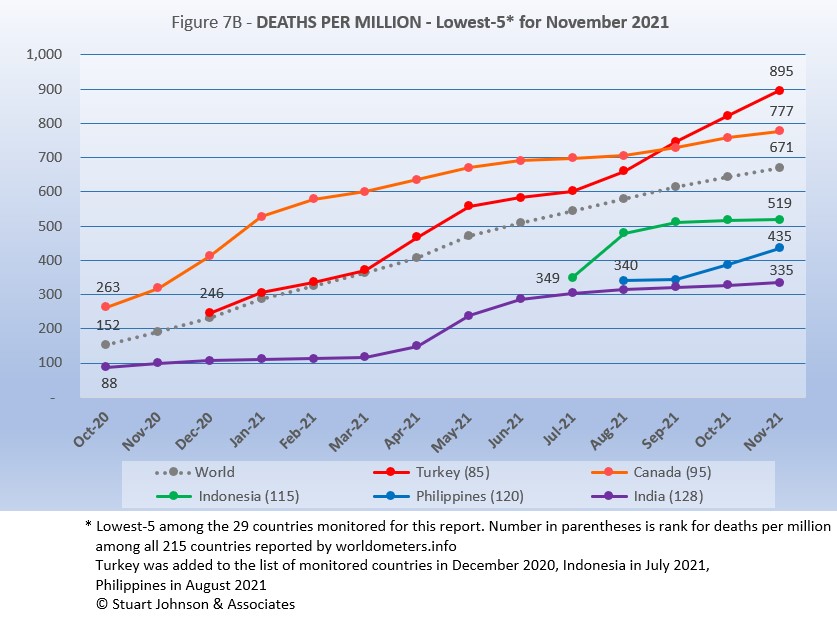

The same five countries return, in the same order for the third month.

Turkey continues a steep rise in deaths-per-million, increasing its lead over the lowest four countries. Canada slowed in late summer, than started to accelerated some, but at a rate slower than the growth of the global level. Indonesia, Philippines, and India all remain below the global level of deaths-per-million. Indonesia, added to the list of monitored countries in July, rose quickly then leveled off for the past three months. Philippines, added to the list in August, started level than began growing faster than the global level. India rose rapidly in May and June, then slowed to a nearly flat pace for the past three months.

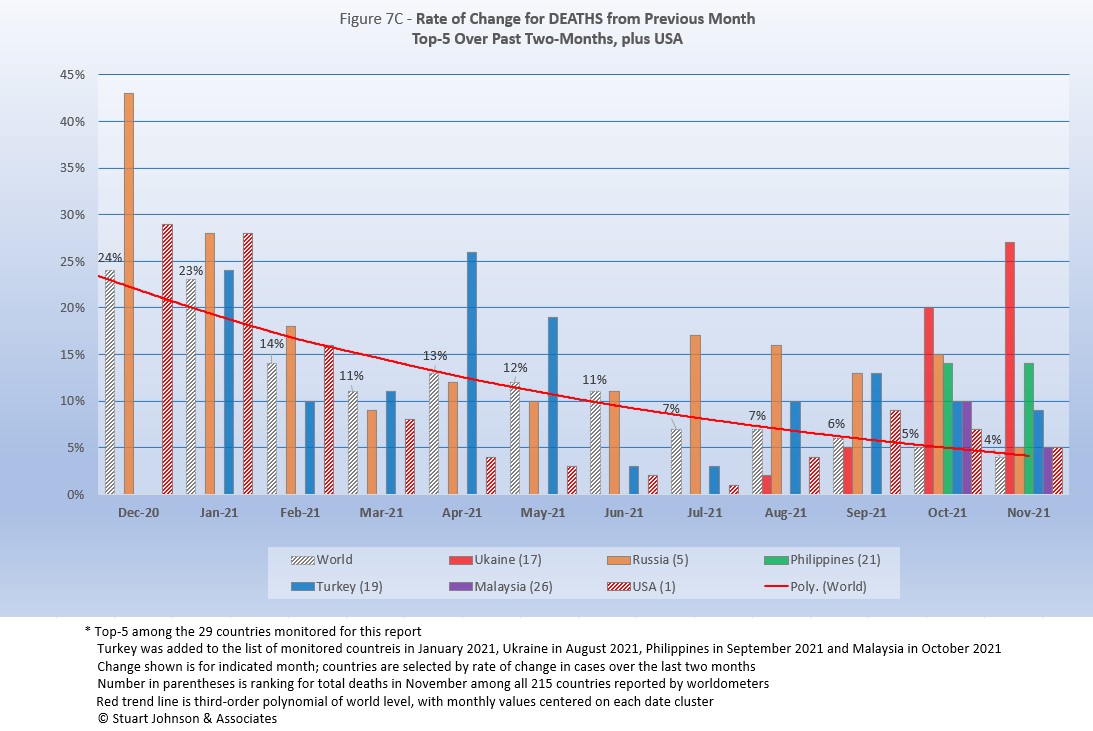

As with the comparable chart for Rate of Change for Cases (Figure 6C), countries for Rate of Change for Deaths (Figure 7C) are selected based on the change over two-months (end of September to end of November) in reported COVID deaths. The focus of the selection is on recent changes, but the chart goes back to November to keep the surges of late 2020 in perspective.

Malaysia replaces Iran this month. The remaining four countries return, with Ukraine swapping places with Philippines in the #1 and #3 spots. . USA appears every month for comparison.

At first glance it may appear that the slope of the trend line for deaths (Figure 7C) starts higher and is more gradual than that for cases (Figure 6C), but the scale of the vertical axis is different, so the global levels are actually fairly close, with the difference coming in how far countries are above the global level. Global change started at 24% (December over November 2020) and ended at 4% for November 2021. (As mentioned with Rate of Change for Cases, the trend line is a polynomial that can change shape as new values are added at the most-recent end.)

All five countries were above the global level of change in deaths in October, but two (Russia and Malaysia) were much closer to the global level in November. Ukraine is the only one with a higher rate of change in November than October, but the selection of countries is based on the change over two months.

USA was lower than the global level of change from February through August, but the past three months it has been slightly above the global level. As I stated last month, all of this confirms the early success of vaccination, which kept driving death rates down, followed by the resurgence related to the delta variant and vaccine resistance. The trend over the past three months is moving down—from 3% over the global level in September to just 1% in November.

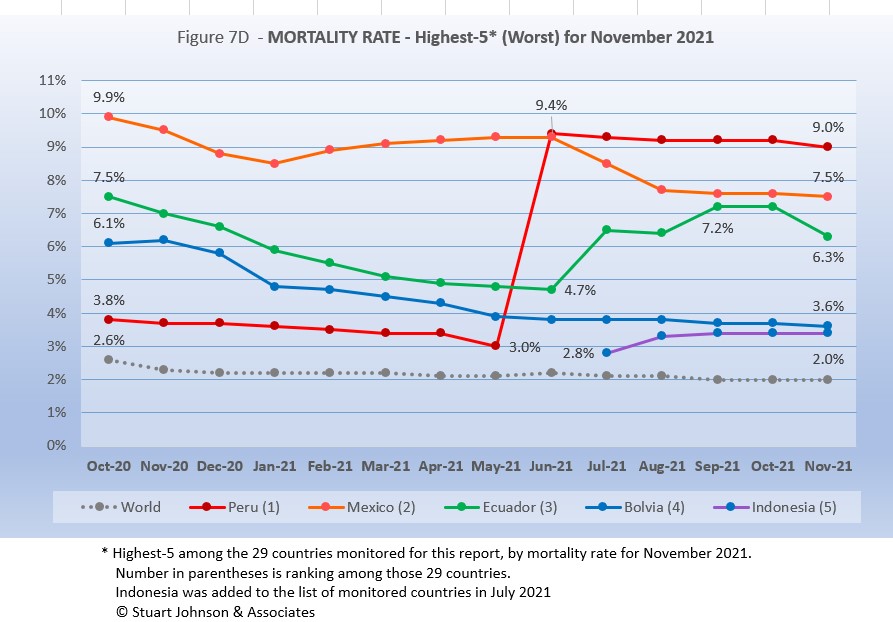

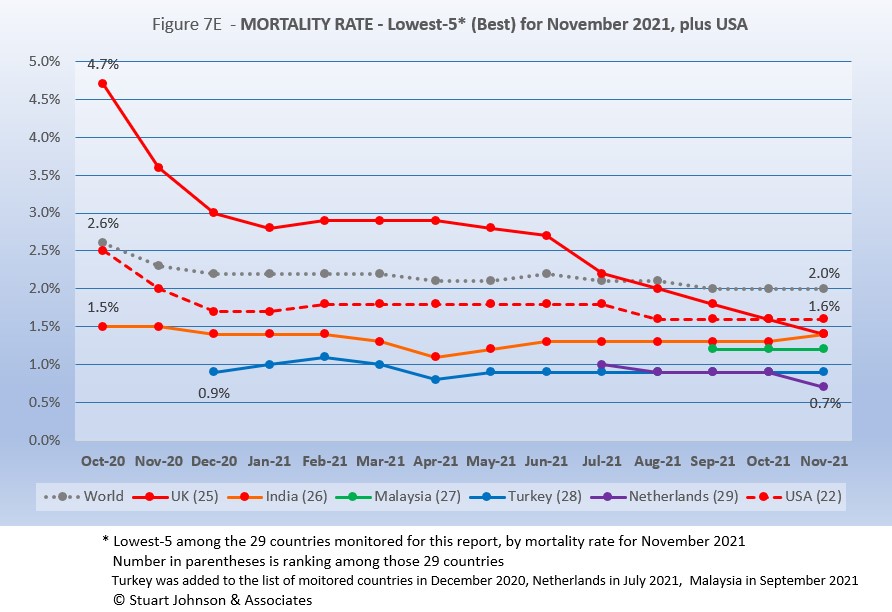

Mortality Rate

Mortality Rates (percentage of deaths against reported cases) have generally been slowly declining. This is not surprising as several factors came into play:

- In the early days of the pandemic, there was a high proportion of "outbreak" cases (nursing homes, retirement communities, other settings with a concentration of more vulnerable people). As the pandemic continued the ratio of "community spread" (with lower death rates) to "outbreaks" increased and the overall Mortality Rate went down.

- As knowledge about treatment increased, mortality went down.

- Since the death count is more certain (though not without inaccuracies), the side of the equation that can change the most is cases. As testing revealed more cases, the Mortality Rate would naturally go down because it would only affect cases and not deaths. In addition, the official numbers do not take into account a potentially higher number of people with the virus who are unreported and asymptomatic, so the real mortality rate could be even lower.

- Vaccinations started in January (though that should impact both cases and deaths).

In recent months, the delta variant produced surges in cases, particularly among those who are unvaccinated, though the death rate stayed lower than early on in the pandemic, which results in a lower mortality rate (remember, however, that deaths from the delta variant may become more evident in coming months).

The Global mortality rate has dropped from 2.6% in October 2020 to 2.1% by April, where it has stayed except for a bump back to 2.2% in June, before dropping again, to 2.0% from September through November. The median for the countries monitored for this report has dropped from 4.8% in October 2020 to 2.8% the past eight months.

All five of the top-5 in mortality rate (among the 29 countries monitored) return in November, in the same order—for the fourth straight month. Despite a generally improving picture for South America, three of the five with the worst mortality rates are located there and Mexico is geographically close.

Peru was in fourth place and declining until June when its corrected death numbers drove Mortality to 9.4%, just ahead of Mexico at 9.3%. Since then Peru has slowly declined, ending November at 9.0%. Mexico started with the highest mortality rate, 9.9%, went down then back up before making a more concerted decline in July, though it has leveled off the last three months. Ecuador was on a steady path of dropping mortality rate through June, then has gone up more than Mexico went down, with the two looking like they would cross paths in August. However, both Mexico and Ecuador leveled off and were running on parallel tracks until Ecuador declined significantly in November.

Bolivia is the one South American country among the five with the worst mortality to show a steady decline (which is good), though the pace of the decline has slowed since May. Indonesia was added to the list of monitored countries in July, coming in at #5, rising some in August, then leveling off to maintain a small but diminishing separation with Bolivia since September, with the two countries headed toward convergence in another month or two. All five have been significantly above the Global rate since at least October 2020 when this chart begins.

Since these represent the best mortality rates, where low is good, the "rank" order is actually in reverse. The same five countries, in the same order, repeat from October.

In spite of the delta variant and its impact on a few countries including USA, mortality rates overall continue to drop. Netherlands, introduced to the list of monitored countries in July, started at 1.0%, spent three months at 0.9%, then dropped to 0.7% in November. Turkey has held steady at 0.9% for seven months. Malaysia has been at 1.2% since being added to the list of monitored countries in September. India started at 1.5%, dropped to a low of 1.1% in April, then slowly moved up (worse) to 1.4% by the end of November. UK has gone from 4.7% in October 2020—well above the global level of 2.0—through a mild roller coaster rise to a strong decline over the past four months, ending November at 1.4%, tied with India.

USA has been below the global level through the time covered by this chart. Starting at 2.5%, it quickly dipped to 1.7% by December 2020, rose to 1.8% for six months, then settled back to 1.6% the past four months. That makes it #19 of the 29 countries monitored (where lower rank represents better mortality), four places above UK.

How real is the threat of death from COVID? That's where successful mitigation comes in. Worldwide, by the end of November, 1 in 30 people have been reported as having contracted COVID and 1 in 1,511 people have died. In USA, while the mortality rate is low, because the number of cases is so high, 1 in 413 have died through November 2021—between Belgium (1 in 430) and Colombia (1 in 396). Belgium with 4% of the USA population and a mortality rate of 1.5% in November; Colombia with 15% of USA population and a mortality rate of 2.5%. Of the 28 countries monitored, India has the lowest impact from death, with 1 death for every 2,943 people. Peru is the worst, at 1 in 164.

With low mortality, USA should have been able to keep deaths much lower, but the extraordinarily high number of cases means more deaths. Without a better-than-global mortality rate, the USA death rate would be far higher. Compared to the mortality rate during the 1918 pandemic, it could be ten times worse than it is. Even at the Global mortality rate of 2.0%, USA would have had 986-thousand deaths (for 49-million cases) by the end of October, instead of 801-thousand with a mortality rate of 1.6%. The response of the health care system and availability of vaccines are part of keeping mortality down, but it's far too early to detail the cause for that positive piece of the COVID picture for USA.

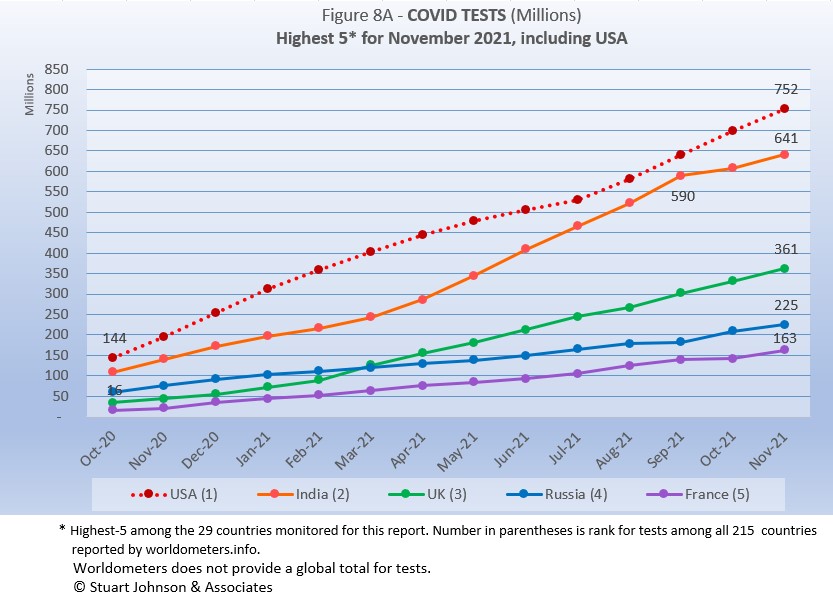

Tests

The same five countries remain on top in COVID testings, having been in the same order since March 2021.

USA remains ahead of other countries in reported COVID tests administered, at 752-million, 17% ahead of India, a wider spread than last month but well below the 56% gap in April. UK continues at the pace it set in February (causing it to move into third place back in March). Russia and France remain on paths of slower growth in raw numbers.

Since these are raw numbers, it is important to recognize the size of the country. It is also the case that COVID tests can be administered multiple times to the same person, so it cannot be assumed that USA has tested almost all of its population of some 331-million. Some schools and organizations with in-person gatherings are testing as frequently as once a week or more for those who are not yet fully vaccinated. That's a lot of testing!

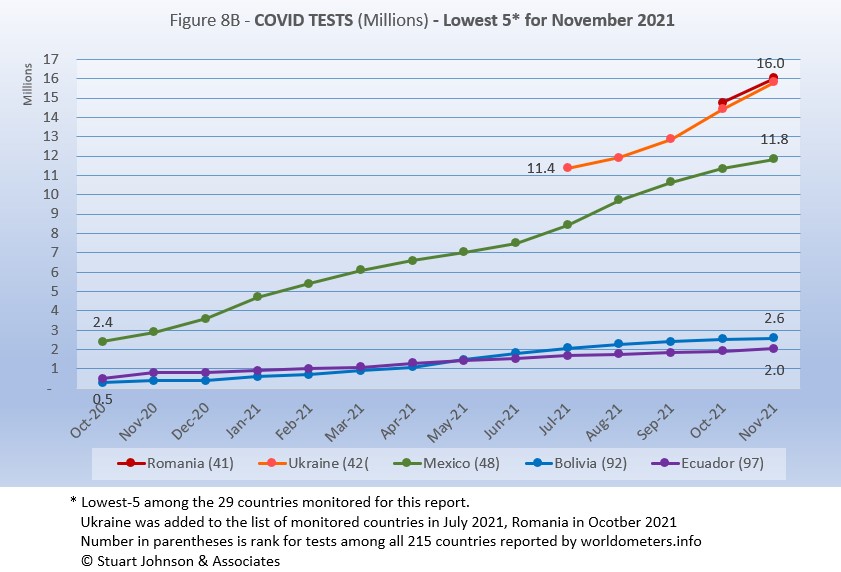

Romania replaces Netherlands. The other four have appeared in the same order since August.

Romania, Ukraine and Mexico all show upward movement in tests while Bolivia and Ecuador remain at the bottom, both at lower rates of growth..

As questions arise about equity of testing between countries, check the number of tests for countries of similar size (within the 29 monitored countries):

- Mexico: 11.8M tests for 128.9M population, compared to Philippines: 24.1M tests for 109.6M population (2X the tests)

- Ukraine: 15.8M tests for 43.7M population, compared to Argentina: 26.2M tests for 45.7M population (1.7X)

- Peru: 20.3M tests for 33.0M population, compared to Malaysia: 37.6M tests for 32.4M population (1.9X)

- Ecuador: 2.0M tests for 17.6M population, compared to Netherlands: 19.2M tests for 17.1M population (9.6X)

- Bolivia: 2.6M tests for 11.7M population, compared to Belgium: 24.6M tests for 11.6M population (9.5X)

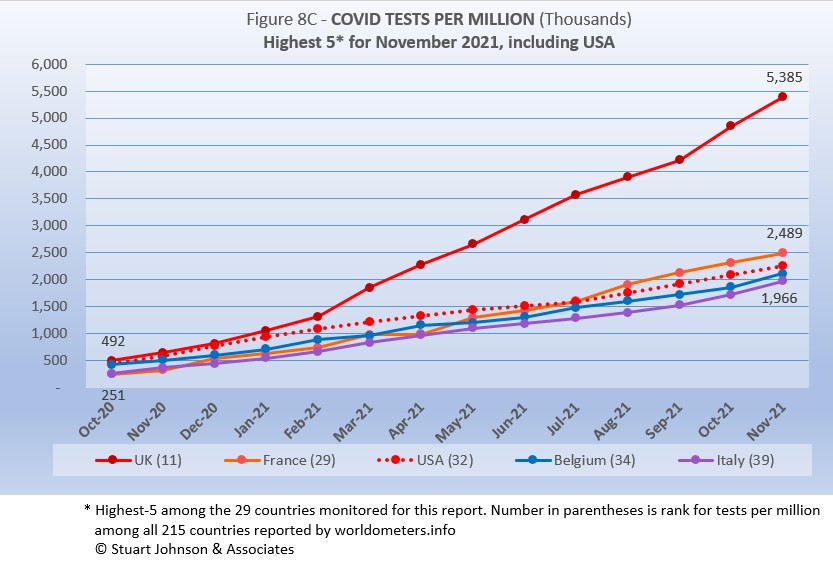

Tests per million adds another perspective. Fig. 8C shows the five countries with the highest tests per million. All five return from October, in the same order since July (though they appear tied, France was slightly ahead of USA in July).

UK, already the most aggressive in testing, increased its numerical lead each month since February, with a reported 5.4-million tests-per-million population in November, more than 5 tests per person. France maintained its lead over USA, ending at 2.5-million tests-per-million, about two-and-a-half tests per person. USA continues on a straight line trajectory, with a very slight dip in June and July, followed by a slight increase for August through November, reaching 2.4-million tests-per-million. Belgium and Italy are not far behind, tracking closely with France and USA. Italy is up to 1.9-million tests-per-million, moving toward 2 tests per person, Belgium passed that benchmark, with 2.1-million tests-per-million.

Anything over 1,000 (or "x-million tests-per-million") represents more tests than people (1,000 on the chart actually means 1,000,000), but as mentioned above, that does not mean that everyone had been tested. Some people have been tested more than once, and some are being tested regularly or with increased frequency.

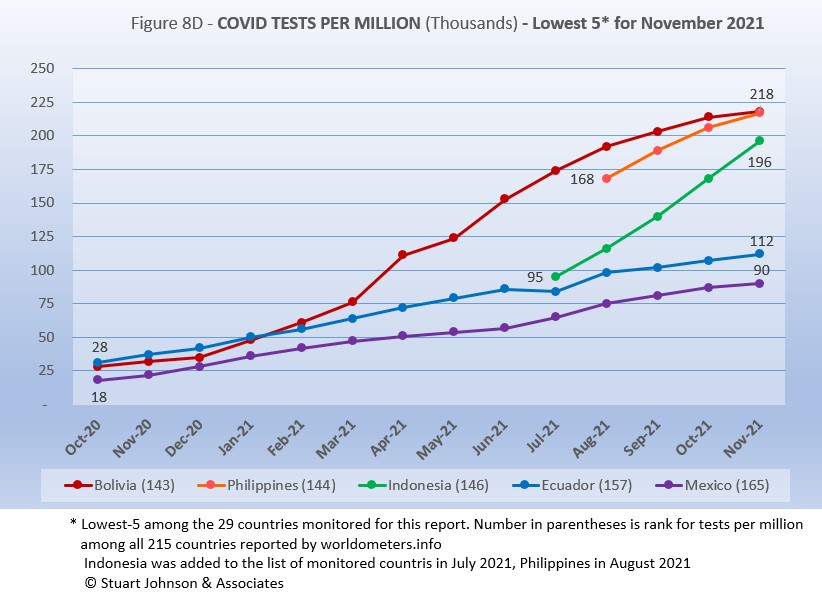

The same five countries have appeared in this order for three months.

While still in the bottom five of the 29 countries monitored for this report, Bolivia has made the most substantial progress. Bolivia has been moving up but experiencing a slowdown in November, hitting 218-thousand tests-per-million. .Philippines is virtually tied at 217-thouand tests-per-million. Indonesia is increasing at a faster rate than seen in Bolivia and Philippines, ending at 196-thousand-tests-per-million and continuing to put more distance between itself and Ecuador and Mexico. Ecuador and Mexico are running in parallel tracks, well below the rate of increase for the other three.

While improvement is evident in all five, the equivalent proportion of tests to population remains very low, from roughly 9% to 22% (and that would be reduced in some individuals receive more than one test). This illustrates the arguments over inequity in resources among countries.

Vaccinations

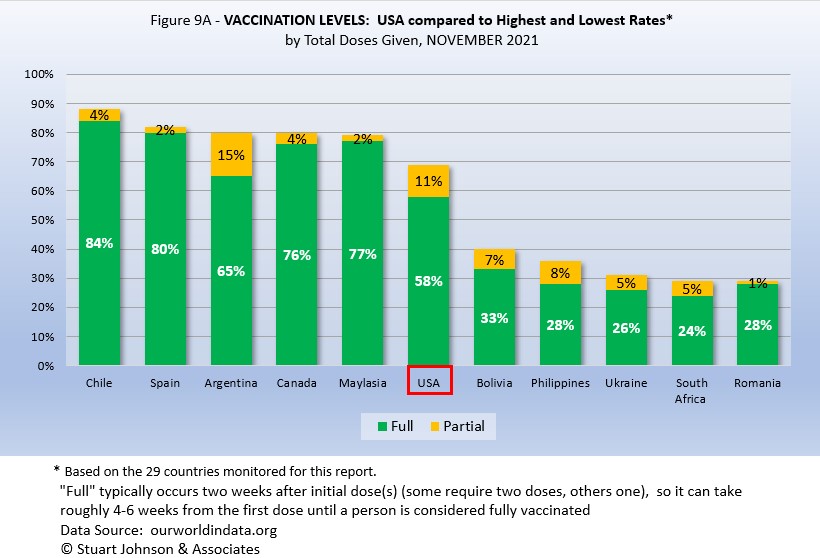

Figure 9A compares USA with the top-5 and bottom-5 of monitored countries by total doses administered. As you can see USA leans toward the upper countries, but is clearly behind Chile, with the highest proportion of fully vaccinated, at 84%. Including partial vaccination, USA comes up to 69%, but that does not even reach the proportion of fully vaccinated in Argentina, with the lowest rate of fully vaccinated in the top-5. On the other hand, USA is well ahead of the bottom five of the 29 monitored countries for either total doses or fully vaccinated.

As pointed out in other parts of this analysis, Figure 9A does not tell the whole story. It's a bit of an apples and oranges comparison, with one major factor being the population of each country.

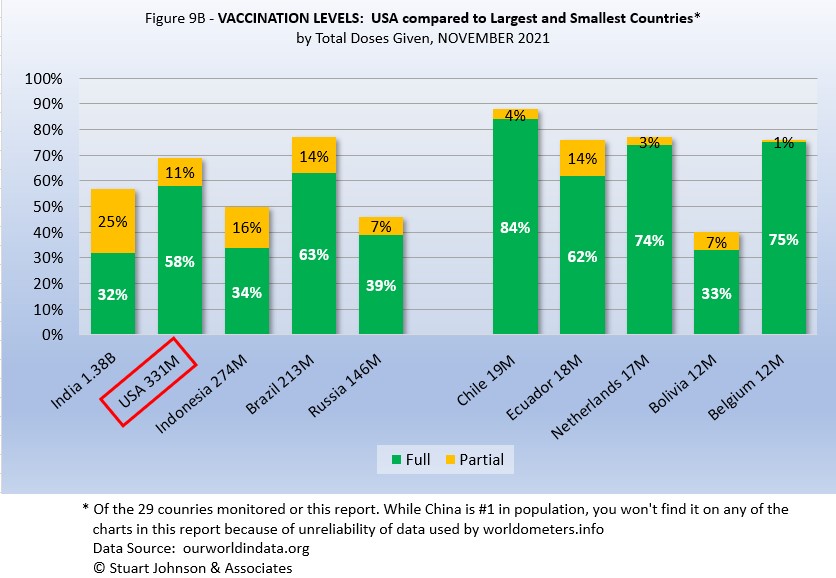

Taking population into account paints a different picture for USA compared to other monitored countries. In Figure 9B you see the five most populous countries on the left and the five smallest (of those monitored for this report) on the right. (China is not included because of unreliability of its data).

Brazil is ahead of USA in both full and total vaccinations, and the fully vaccinated of both exceed the total doses of India, Indonesia, and Russia.

On the side of smallest countries, all except Bolivia are ahead of USA in fully vaccinated. Chile is far ahead of all ten in total and fully vaccinated. Netherlands is tied with Brazil for total vaccinations, Ecuador and Belgium are only one point behind at 76%, but all three exceed Brazil's 63% fully vaccinated.

Thus, individual regions, provinces or states of the largest countries may be doing as well as some smaller countries, while the entire country lags behind the smaller ones.

Causes of Death in U.S.

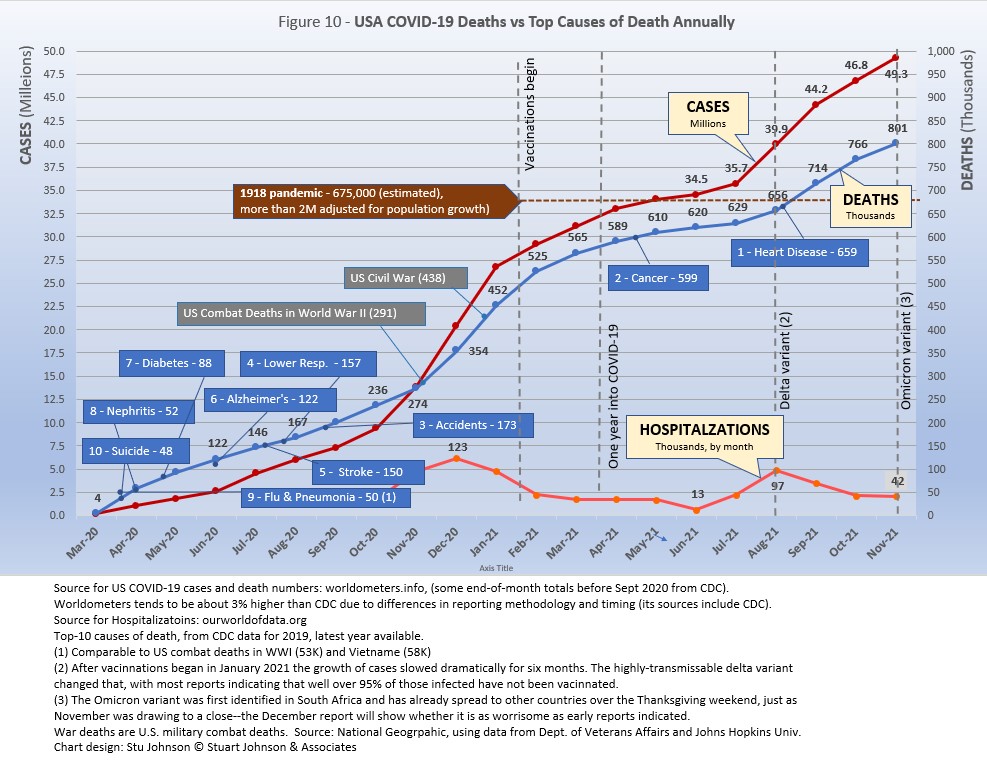

New this month is the addition of the curve for USA Hospitalizations by month, which shows the correlation with surges in cases, followed by a rise in cumulative deaths.

Early in the reporting on COVID, as the death rate climbed in the U.S., a great deal of attention was given to benchmarks, most notably as it approached 58,000, matching the number of American military deaths in the Vietnam War. At that time, I wrote the first article in this series, "About Those Numbers," in which I looked at ways of viewing the data, which at the time of that writing in May 2020 was still focused on worst-case models and familiar benchmarks, like Vietnam.

Figure 10 shows the number of USA COVID cases and deaths against the top-10 causes of death as reported by CDC. Last month, that data was updated to show 2019 figures, the latest year available. Except for Flu & Pneumonia and Nephritis, which swapped the #8 and 9 positions, the others stayed in the same order and changed by small increments, if at all, but did mean that some of the benchmarks in the chart moved slightly.

Notice that for nearly nine months, the curve for deaths was increasing at a faster rate than cases. Then, starting in October 2020 the curve for cases took a decided turn upward, while deaths increased at a more moderate pace (the two curves use different scales, but reflects the relative rate of growth between them).

Media reporting tended to focus on easily grasped benchmarks—deaths in Vietnam or World War II, or major

milestones like 500,000 (crossed in February 2021).

In August we passed the 2018 level for heart disease (655-thousand), then passed it again in September when the 2019 data "moved the goal post" to 259-thousand. Another significant benchmark, pointed out in some news reports, was the 675-thousand estimate for deaths in USA during the 1918 pandemic. Adjusted for population growth, however, that number would now be around 2-mllion.

Having passed the annual death benchmarks, now we can only watch as the numbers continue to climb...

The latest "Ensemble Forecast" from CDC suggests that by our next report we should see:

...the number of newly reported COVID-19 deaths will remain stable or have an uncertain trend over the next 4 weeks, with 6,200 to 11,400 new deaths likely reported in the week ending December 25, 2021. The national ensemble predicts that a total of 805,000 to 817,000 COVID-19 deaths will be reported by this date.....

Note: As I've referenced in the notes for several charts, the data from worldometers.info tends to be ahead of CDC and Johns Hopkins by about 3%, because of reporting methodology and timing. I use it as a primary source because its main table is very easy to sort and provides the relevant data for these reports. Such differences are also found in the vaccine data from ourworldindata. Over time, however, trends track with reasonable consistency between sources.

Perspective

The 1918-19 Spanish Flu pandemic is estimated to have struck 500 million people, 26.3% of the world population of 1.9-billion at that time. By contrast, we're now at 3.1% of the global population. Deaths a century ago have been widely estimated at between 50- and 100-million worldwide, putting the global mortality rate somewhere between 10 and 20-percent. It has been estimated that 675,000 died in the U.S.

IF COVID-19 hit at the same rate as 1918, we would see about 2-billion cases worldwide by the time COVID-19 is over, with the global population now at 7.9-billion—four times what it was in 1918. There would be 200- to 400-million deaths. The U.S. is estimated to have had 27-million cases (one-quarter of the population of 108-million) and 675,000 deaths. Today, with a population of 331-million (a three-fold increase from 1918) this would mean more than 80-million cases, and 2- to 4-million deaths.

However, at the present rate of confirmed cases and mortality while the total number of global cases could approach 500 million or more—comparable to 1918 in number, that would be one-quarter of 1918 when taking population growth into account . .. and assuming the pandemic persists as long as the Spanish Flu, which went on in three waves over a two year period. At the present rate of increase (close to 13.1-million cases per month) it would take another 18 months to reach 500-million, roughly June of 2023.

If the total number of cases globally did approach 500-million, using the global mortality rate of 2.0% in November, there would be roughly 10-million deaths worldwide. Tragic but far below the number reported for 1918 (50-million) with an even wider gap (200 million) when taking population growth into account.

Earlier in the summer, I indicated that with vaccination in progress and expected to be completed in the U.S. by the end of summer, the end of COVID-19 could come sooner. Like 1918, however, there are now complicating factors, such as the combination of the delta variant with a high number of unvaccianted (some by choice, as in USA and Europe, and many more in underdeveloped countries by inequitable access to vaccine). Now, we have the additional unknown of the omicron variant. While we may have thought the end of the pandemic was in sight, it is still too early to make predictions on the duration and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic globally. Indeed, the slope of the global growth of cases and deaths still looks like the trajectory of an airplane climbing toward cruising altitude.

Despite the darkening forecast since delta and omicron, the vast difference in scale between the Spanish Flu pandemic a century ago and COVID-19 even more than a year-and-a-half in, still cannot be denied.. Key differences are the mitigation efforts, treatments available today (though still leaving the health care system overwhelmed in some areas during surges), and the availability of vaccines. In addition, in 1918 much of the world was focused on a brutal war among nations (World War I) rather than waging a war against the pandemic, which ran its course and was undoubtedly made much worse by the war, with trans-national troop movements, the close quarters of trench warfare, and large public gatherings supporting or protesting the war.

Vaccinations in the U.S.

With remarkable speed (it usually takes years to develop vaccines), two COVID vaccines were granted emergency approval for use in the U.S. starting in January 2021—the one by Pfizer requires super-cold storage, which limits its deployment. The other, by Moderna, requires cold storage similar to other vaccines. Both of these require two doses, which means that vaccine dosages available must be divided in two to determine the number of people covered. By March 2021 Johnson & Johnson had been granted approval for a single-dose vaccine. The numbers in Figure 11 represent the status of all three vaccines as of November 30 (as reported by CDC, which will be slightly different than ourworldofdata data used in earlier vaccination charts). .

A person is considered "fully vaccinated" two weeks after the final (or only) vaccine dose; roughly five to six weeks total for Pfizer and Moderna and two weeks for Johnson & Johnson.

Figure 11 shows an upturn in Doses Distributed and Administered in August, a sign that perhaps the delta variant provided the impetus for increased vaccinations. The rate of increased distribution continued into November. Doses administered dipped slightly in September then recovered in October and November. The good news is the visible increase in fully vaccinated in November—up 3.6% from October, most of that from opening vaccinations to those ages 12-18). Added to the chart last month was a timeline for the number of booster doses administered. In addition, in early November the CDC expanded vaccination approval for children ages 5-12 and there were promising developments for one or more drugs to treat those with COVID infections.

Debates over masking policy and mandatory vaccination provides evidence that the real battle now is vaccination. A year ago we were debating lock-downs. Today the debate is how to be open but remain safe. Will the rise of infections and the call for more masking be enough to spur more vaccinations? For some, perhaps, but whether low levels of vaccinations have prolonged the pandemic (around the world) will be the subject of discussion and debate for years to come.

Vaccinating over 300 million people in the United States (much less a majority of the billions around the world) is a daunting task. It is a huge logistical challenge, from manufacture to distribution to administration. Yet, it is amazing that any of this is possible this soon after the identification of the virus just over 20 months ago—and that according to available data, more than half of the world's population of 9.8-billion have been at least partially vaccinated.

There is a delicate balance between maintaining hope with the reality that this is a huge and complicated logistical operation that will take time, with the prospect that COVID will be with us for some time—morphing from a global pandemic to an ongoing endemic like seasonal flu (more on this below)—partly because getting shots into the arms of the unvaccinated is proving to be a far bigger challenge than most officials assumed a few months ago.

As the richer countries with access to more resources make progress, the global situation is raising issues of equity and fairness within and between countries. Even as the U.S. and other countries launch large scale vaccine distribution to a needy world community, the immensity of the need is so great that a common refrain heard now is whether this aid is too little, too late. As COVID fades into a bad memory in countries able to provide help, will the sense of urgency remain high enough to produce the results needed to end this global pandemic?

Maintaining Perspective

In the tendency to turn everything into a binary right-wrong or agree-disagree with science or government, we ignore the need to recognize the nature of science and the fact that we are dealing with very complicated issues. So, in addition to recommending excellent sources like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it is also wise to consider multiple qualified sources.

While there has been much focus placed in trusting "the science," it is important to recognize that science itself changes over time based on research and available data. In the highly volatile political atmosphere we find ourselves in (not just in the U.S., but around the world), there is a danger of not allowing the experts to change their views as their own understanding expands, or of trying to silence voices of experts whose views are out of sync with "the science" as reported by the majority of media outlets.

In an earlier report, I mentioned the Greater Barrington Declaration, currently signed by nearly 58-thousand medical & public health scientists and medical practitioners, which states "As infectious disease epidemiologists and public health scientists we have grave concerns about the damaging physical and mental health impacts of the prevailing COVID-19 policies, and recommend an approach we call Focused Protection."

For a personal perspective from a scholar and practitioner who espouses an approach similar to the Focused Protection of the Greater Harrington Declaration, see comments by Scott W. Atlas, Robert Wesson Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, in an article "Science, Politics, and COVID: Will Truth Prevail?"

Several months ago on SeniorLifestyle I posted an article by Mallory Pickett of The New Yorker, "Sweden's Pandemic Experiment," which provides a fair evaluation of the very loose protocols adopted by Sweden, essentially a variation of the "Focused Protection" approach. The "jury is still out" on this one, so judge for yourself whether Sweden hit the mark any better than the area in which you live.

UPDATE ON SWEDEN: Very little change from July. In early December Sweden reported just over 1.2-million cases of COVID, or 11.9% of its population of 10.2-million. There have been 15,136 deaths, for a mortality rate of 1.2%. Ranked 89 by population, Sweden was number 36 in cases and number 45 in deaths (October was #34 in cases, #45 in deaths). Hospitalizations rose 11% in November, up 27 to 272, compared to a 3% drop (8 cases) in October.

That would put Sweden below USA (15.5%) and between Argentina (11.6%) and Spain (11.0%) in cases as proportion of population, but the mortality rate is the same as India, near the bottom (best) among the 29 counties monitored for this report and well below the global rate of 2.0%.

FROM PANDEMIC TO ENDEMIC: After posting last month's Perspectives, I posted on SeniorLifesytle an article by Sarah Zhang from The Atlantic, "America Has Lost the Plot on COVID." In it, she suggests that America (and the world) is headed not toward the eradication of COVID-19, but its transformation from pandemic to endemic, joining the seasonal flu as something we will deal with for some time. Getting there, she contends, is more a matter of mixed policy strategies than "following the science," but coming to grips with its inevitability could help lead to more effective strategies.

Zhang mentions Denmark as a counterpoint to what is happening in America, saying

One country that has excelled at vaccinating its elderly population is Denmark. Ninety-five percent of those over 50 have taken a COVID-19 vaccine, on top of a 90 percent overall vaccination rate in those eligible. (Children under 12 are still not eligible.) On September 10, Denmark lifted all restrictions. No face masks. No restrictions on bars or nightclubs. Life feels completely back to normal, says Lone Simonsen, an epidemiologist at Roskilde University, who was among the scientists advising the Danish government. In deciding when the country would be ready to reopen, she told me, “I was looking at, simply, vaccination coverage in people over 50.” COVID-19 cases in Denmark have since risen—under CDC mask guidelines, the country would even qualify as an area of “high” transmission where vaccinated people should still mask indoors. But hospitalizations are at a fraction of their January peak, relatively few people are in intensive care, and deaths in particular have remained low.

Crucially, Simonsen said, decisions about COVID measures are made on a short-term basis. If the situation changes, these restrictions can come back—and indeed, the health minister is now talking about that possibility. Simonsen continues to scrutinize new hospitalizations everyday. Depending on how the country’s transition to endemicity goes, it could be a model for the rest of the world.

UPDATE ON DENMARK: In early December, Denmark reported nearly 497-thousand cases of COVID, or 8.5% of its population of 5.8-million (up from 6.8% a month ago, or 101-thousand cases). There have been 2,912 deaths, for a mortality rate of 0.6% (up 190 from a month ago, dropping the mortality rate by 0.1%). Ranked 113 in population, Denmark was number 64 in cases and number 95 in deaths (same rank for deaths as a month ago, but rank for cases rose 6 places from 70). Hospitalizations rose 78% in November, up 181, to 414 (compared to a 151% increase in October), but that remarkably is still only 0.2% of the increase in cases.

That puts Denmark at about 70% the proportion of cases as Sweden, even better compared to USA, and close to Italy (8.3%, ranked 14 among the 29 countries monitored for this report). While more than double the global case to population proportion of 3.3%, mortality rate is most striking, and the point of Zhang's observation about focusing on the prevention of hospitalization. The mortality rate (0.6%) is below Netherlands (0.7%), which is the lowest among the 29 monitored countries, and well below the global rate of 2.0%.

How we evaluate the many approaches used to deal with COVID will determine how we prepare for and approach the next global event—including what now appears to be a transition from pandemic to endemic for COVID-19.

My purpose in mentioning these sources is to recognize that there are multiple, sometimes conflicting, sometimes dissenting, voices that should be part of the conversation. The purpose of these monthly reports remains first and foremost to present the numbers about COVID-19 in a manner that helps you understand how the pandemic is progressing and how the U.S. compares to the world—and how to gain more perspective than might be gathered from the news alone.

Profile of Monitored Continents & Countries

(Data from worldometers.info).

| Rank | Country | Population | Share of World Population |

Density People per square km |

Urban Population |

Median Age |

| WORLD | 7.82B | 100% | -- | -- | -- | |

| Top 10 Countries by Population, plus Five Major Continents See lists of countries by continent |

||||||

| - | ASIA | 4.64B | 59.3% | 150 | 51 countries | 32 |

| 1 | China | 1.44B | 18.4% | 153 | 61% | 38 |

| 2 | India | 1.38B | 17.7% | 454 | 35% | 28 |

| - | AFRICA | 1.34BM | 17.1% | 45 | 59 countries | 20 |

| - | EUROPE | 747.7M | 9.6% | 34 | 44 countries | 43 |

| - | S AMERICA | 653.8M | 8.4% | 32 | 50 countries | 31 |

| - | N AMERICA | 368.9M | 4.7% | 29 | 5 countries | 39 |

| 3 | USA | 331.5M | 4.3% | 36 | 83% | 38 |

| 4 | Indonesia** | 274.5M | 3.5% | 151 | 56% | 30 |

| 5 | Pakistan* | 220.9M | 2.8% | 287 | 35% | 23 |

| 6 | Brazil | 212.9M | 2.7% | 25 | 88% | 33 |

| 7 | Nigeria* | 206.1M | 2.6% | 226 | 52% | 18 |

| 8 | Bangladesh* | 165.2M | 2.1% | 1,265 | 39% | 28 |

| 9 | Russia | 145.9M | 1.9% | 9 | 74% | 40 |

| 10 | Mexico | 129.3M | 1.7% | 66 | 84% | 29 |

| *these countries do not appear in the details because they have not yet reached a high enough threshold to be included **Indonesia was added to the monitored list in July 2021 Other Countries included in Analysis most have been in top 20 of cases or deaths |

||||||

| Rank | Country | Population | Share of World Population |

Density People per square km |

Urban Population |

Median Age |

| 13 | Philippines (2) | 109.6M | 1.4% | 368 | 47% | 26 |

| 17 | Turkey | 84.3M | 1.1% | 110 | 76% | 32 |

| 18 | Iran | 83.9M | 1.1% | 52 | 76% | 32 |

| 19 | Germany | 83.8M | 1.1% | 240 | 76% | 46 |

| 21 | United Kingdom | 67.9M | 0.9% | 281 | 83% | 40 |

| 22 | France | 65.3M | 0.8% | 119 | 82% | 42 |

| 23 | Italy | 60.4M | 0.8% | 206 | 69% | 47 |

| 25 | South Africa (1) | 59.3M | 0.8% | 94 | 67% | 28 |

| 29 | Colombia | 50.9M | 0.7% | 46 | 80% | 31 |

| 30 | Spain | 46.8M | 0.6% | 94 | 80% | 45 |

| 32 | Argentina | 45.2M | 0.6% | 17 | 93% | 32 |

| 35 | Ukraine (1) | 43.7M | 0.6% | 75 | 69% | 41 |

| 39 | Poland (1) | 37.8M | 0.5% | 124 | 60% | 42 |

| 39 | Canada | 37.7M | 0.5% | 4 | 81% | 41 |

| 43 | Peru | 32.9M | 0.4% | 26 | 79% | 31 |

| 45 | Malaysia (3) | 32.4M | 0.4% | 99 | 78% | 30 |

| 61 | Romania (4) | 19.1M | 0.2% | 84 | 55% | 43 |

| 63 | Chile | 19.1M | 0.2% | 26 | 85% | 35 |

| 67 | Ecuador | 17.6M | 0.2% | 71 | 63% | 28 |

| 69 | Netherlands (1) | 17.1M | 0.2% | 508 | 92% | 43 |

| 80 | Bolivia | 11.7M | 0.1% | 11 | 69% | 26 |

| 81 | Belgium | 11.6M | 0.1% | 383 | 98% | 42 |

(1) Added to the monitored list in July 2021 |

||||||

Scope of This Report

What I track

From the worldometers.info website I track the following Categories:

- Total Cases • Cases per Million

- Total Deaths • Deaths per Million

- Total Tests • Tests per Million (not reported at a Continental level)

- From Cases and Deaths, I calculate the Mortality Rate

Instead of reporting Cases per Million directly, I try to put raw numbers in the perspective of several key measures. These are a different way of expressing "per Million" statistics, but it seems easier to grasp.

- Country population as a proportion of global population

- Country cases and deaths as a proportion of global cases and deaths

- Country cases as a proportion of its own population

- Cases and deaths expressed as "1 in X" number of people

Who I monitor

My analysis covers countries that have appeared in the top-10 of the worldometers categories since September 2020. This includes most of the world's largest countries as well as some that are much smaller (see the chart in the previous section).

This article was also posted on

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: December 337, 2021 Accessed 5,257 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: Information / Topics: History • Information • Statistics • Trends

COVID-19 Perspectives for November 2021

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: December 337, 2021

Europe takes the brunt of the latest surge, just as Omicron, another potentially dangerous variant, arrives to dampen the holiday season…

Putting the COVID-19 pandemic in perspective (Number 17)

This monthly report was spawned by my interest in making sense of numbers that are often misinterpreted in the media or overwhelming in detail (some would say that these reports are too detailed, but I am trying to give you a picture of how the COVID pandemic in the United States compares with the rest of the world, to give you a sense of perspective).

These reports will continue as long as the pandemic persists around the world.

Report Sections:

• November-at-a-glance

• The Continental View • USA Compared with Other Countries

• COVID Deaths Compared to the Leading Causes of Death in the U.S.

• U.S. COVID Cases versus Vaccinations

• Profile of Monitored Continents & Countries • Scope of This Report

November-at-a-glance

- COVID-19 continued to spread around the world, reaching 263-million cases by the end of November, up 6% from October. Deaths from COVID around the world rose to 5.2-million, up 4% after crossing the 5-million mark in October.

The level of reported cases represents 3.3% of the global population of 7.9-billion, up from 3.1% at the end of October. The increase over October remained steady, at 6%, back to the level of May following an apparent delta-related surge, when the monthly increase went up to 10% in August. That means that so far the delta-related surge was not as significant as previous surges (November 2020-January 2021 and April-May 2021), but continues to be problematic. In some areas it is driven by dense populations and/or lack of vaccine, in others (USA being a prime example) by vaccine resistance as evidenced by reports that hospital admissions for COVID are nearly all among those who have not been vaccinated. Adding concern as the month closed was the identification of the omicron variant by South African researchers. More on this below.

The blue "cone" in Figure 1 shows the possible high and low projection of global cases, with the bottom (roughly 150-million) representing the trajectory of the lower pace in late summer 2020 and the upper (approximately 300-million) representing a continuation of the surge from November 2020 through January 2021. You can see that the curve for global cases has bent down and back up several times since February 2021, but is very slowly moving away from—but still close to—the upper edge of the prediction cone. USA had fared better until August, which I'll get to below. - The pattern for deaths tends to lag behind cases by weeks or months, and the global rate of increase continues to fall below that of cases—dropping from a 23% increase in January to 4% at the end of November, with a modest increase to 7% in July and August. While the curve for deaths is not increasing as much as that for cases, it is still climbing at a noticeable rate (unlike USA where cases and deaths flattened between January and July 2021, before rising again).

- Where South America was clearly going the wrong way through early summer, things have significantly reversed. Headed toward eclipsing Europe (the trouble spot in November) in the number of cases and deaths, the curves began to turn down in July and flatten through November.

South America has also taken the lead in vaccination doses, surpassing Europe and North America in August. Ironically, while the continent is improving several South American countries remain as trouble spots. See more in The Continental View.

- USA. continues to lead the world in the number of reported cases and deaths, but also leads the world in the number of COVID tests and is respectable in vaccinations, but hampered by vaccine resistance.

While the 18.8% USA share of global cases at the end of November was down from a high of 25.9% in January, the trend is erratic. The rate was 18.9% in June before dropping to 18.0% in July, then headed back up to 18.9% in September and October.

Similarly, deaths have declined from 20.9% of the world total in September 2020 to 14.5% at the end of August 2021 before heading back up to 15.5% at the end of November. As you will see in details to follow, while USA outpaced everyone through the early months of the pandemic, the vast disparity was slowly shrinking until the delta variant brought a resurgence in cases.

The projection cone surrounding USA Cases in Figure 1 shows a pronounced flattening of the curve from January to July (vaccinations), with a very noticeable upward bend in August (delta variant among unvaccinated)—though still in the bottom half of the projection cone (which for USA extends from roughly 40- to 90-million). The upward bend for USA cases from August to November is clearly visible in Figure 1, but even more pronounced in Figure 10 below, which "zooms in" on USA.

Figure 1 also shows how much lower cases in the US would be—approaching 11-million by now, instead of 49.3-million—if they were proportional to the global population. It would also mean about 176-thousand deaths instead of 801-thousand.

- The omicron variant represents a new potential threat to spreading and prolonging the COVID pandemic. Yet, it is early. While the delta variant has been a factor, its impact has been uneven globally and its extent less than the massive surge felt globally between November 2020 and January 2021. We will not know the true nature and potential impact of omicron for weeks as researchers dig deeper. For a good overview of this process, see "We won't know how bad omicron is for another month" by Antonio Regalado, reported in the MIT Technology Review.

- Countries to watch. No countries have been added to the list of countries I monitor. The weekly comparison report on worldometers, however, gives a sense of hot spots to watch. Based on activity in the last week or two, this includes Czechia, Vietnam, Hungary, Austria, Slovakia, Switzerland, and Greece. While some of these have population too small to make much of an impact on this report, they generally confirm (along with countries recently added to my monitored list) that the shift toward southeast Asia and the Middle East in the past several months has shifted to renewed surges in Europe, which are casting a pale on the holiday season.

- With vaccinations, USA continues to move ahead. After a noticeable slowdown in June and July, total doses distributed climbed to more than 573-million by November. The curve for doses administered ("shots in the arm") picked up after a slight slowdown in September. Meanwhile, the curve for those fully vaccinated rose noticeably in November, to 231-million, up 3.6% from October (See Figure 11).

Where you get information on COVID is important. In an atmosphere wary of misinformation, "news-by-anecdote" from otherwise trusted sources can itself be a form of misinformation. As I go through the statistics each month, I am reminded often that the numbers do not always line up with the impressions from the news. With that caveat, let's dig into the numbers for November 2021.

The Continental View

The most obvious change in November is the surge in COVID cases in Europe. The other major continents either continued at their recent pace or slowed somewhat in growth of cases. Oceana is not included because of its small size, about one-half a percent of world population.

While COVID-19 has been classified as a global pandemic, it is not distributed evenly around the world.

Asia accounts for 59.4% of the world's population (Figure 2), but had only 31.3% of COVID cases at the end of November (Figure 3A)—affecting a mere 1.7% of its population—down from a high of 32.3% in September. (COVID cases now represent 3.3% of world population).

The biggest trends in the proportion of cases among continents are most noticeable since March:

- Asia - rising to a peak of just over 32% in September, then declining slowly the last two months

- Europe - falling through September from a high of nearly 31% in March, with a bump up to 26% in October and a sharper surge to 28% in November

- North America - falling through July from a high of nearly 30% in January, then back up slightly, but remaining below 23%

- South America - after peaking at 18% in June, steadily descending to just under its low of 15% in November

- Africa - hovering around 3.5%

Where Asia and Africa combined represent about three-quarters (76.9%) of the world's 7.9-billion people, Europe, South America and North America still account for nearly two-thirds of COVID cases (65.3% - Figure 3A) and about 7 in 10 of COVID deaths (72.4% - Figure 4A). The shares for Europe and the Americas combined were slowly coming down from their highs (74.7% for cases and 80.8% for deaths in February), but have inched back up a fraction of a percent each month since September. Since South America has been declining overall, that increase is driven by Europe and North America.

While news reports continue to give the impression of widespread delta-variant surges, growth in the number of cases since July has not been uniform across continents. Asia and North America both showed an upturn in cases for August and September, but slowed in October and November. Europe, on the other hand, showed a more restrained increase in rate between July and September, with a slight acceleration in October, followed by a significant surge in November.

Meanwhile, South America actually started to level off in July, while Africa experienced a noticeable increase in cases from June through August before leveling off again, maintaining its unique position far below the other major continents in the raw number of cases.

The raw numbers of Figure 3B can be deceptive. Figure 3C gives a more realistic picture of impact by translating raw case numbers to percentage of population. The shape of the curves is similar to those for raw numbers, but the order and spacing paints a different picture.

After a sharp increase in January, North America slowed down for six months, before jumping 1.5 points to 13.0% in August, continuing that pace into September before slowing slightly, ending November with COVID cases representing 15.9% of its population.

Europe remains well below North America, though its proportion of cases rose sharply from 7.9% in September to 9.8% in November. At the same time that Europe was trending upward, South America saw its curve flatten, rising only 0.5% since August, ending November at 5.9% of COVID cases in its population.

Asia and Africa, the two largest continents, remain at the bottom by proportion of COVID cases for their populations. Asia increased more noticeably than Africa between April and September, but both ended well below the global level of 3.3% at the end of November—Asia at 1.7% and Africa at 0.6%. In fact, it is the low proportions of Asia and Africa that have held the global curve to a nearly straight line progression. Omicron, the newest variant, first reported in South Africa at the end of November, could change that, with growing arguments over inequities in global vaccine distribution affecting the ongoing spread of COVID.

The proportion of deaths between continents is even more distorted than that of cases. In the early months of COVID, Europe and the Americas were growing in deaths, causing Asia to bottom out in its proportion of global deaths at 15.2% in March. The trends since then shadow those of cases, but lag behind by a month of two.

- Europe retains the highest proportion of COVID deaths at 26%, up a full percentage point in November, but down from its high of nearly 33% in April—still nearly three times its nearly 10-percent share of world population.

- Asia ended November just over 23% of world COVID deaths, down one-tenth of a percent each of the last three months, still well above its low just above 15% in March—and far below its 59% proportion of world population.

- South America and North America are nearly tied at slightly less than 23% at the end of November. South America is down from its high of nearly 26% in July, North America below its high of nearly 30% in February, but above its low of just under 22% in August. Like Europe, both are well above their proportion of world population (8% for South America, nearly 5% for North America).

- Africa has hovered around 4%, with the last four months pushing upward slightly, but far below its 17% share of world population.

Deaths through October shows that while the trajectory lags behind cases and has progressed at a steadier rate, it does reflect the overall changes in Cases by continent. Except for Africa, which is well below the other continents in the number of COVID deaths, for the other four the 1-million milestone is history.

Europe remains at the top in number of deaths, at 1.4-million. South America was headed toward passing Europe back in the surge of early summer, then flattened, even as the delta variant was causing surges elsewhere. North America leveled off after vaccinations began in January, then started moving up again with the combination of vaccine resistance and the delta variant. Asia started to accelerate in May, on a path to join Europe, but started to slow in the last two months. The result of these wandering curves is that Asia and the Americas came even closer to convergence in November than we saw last month.

Meanwhile, Africa progressed at a fairly steady pace, well below the others both in level and rate of change, despite being second in size, with 1.3-billion people.

Vaccinations

As Figure 5A shows,more than four in ten of the global population has been reported as fully vaccinated (roughly 3.5 billion people), with another 10% having received the first of two doses or in the waiting period to be considered fully vaccinated. Given continuing gloomy reports in the news, those numbers may be surprisingly high given the monumental task of vaccinating multiple billions of people.

South America took the lead in total vaccinations in November (73%), but is tied with Europe for the proportion who are fully vaccinated (58%). North America comes next, putting the three smallest continents by population over the 50% threshold for full vaccinations. Asia follows with 63% partially vaccinated and just under half (48%) fully vaccinated. Africa remains far below, with 11% having had at least one dose.

While South America got into vaccinations later and slower than North America and Europe, Figure 5B shows how it pushed its way to the top of the total vaccination doses administered by August, expanding its lead since then—and this by proportion of population, not raw numbers, so it's a fair comparison. Where North America started aggressively, it slowed in June as Europe caught up, then began to move ahead slightly, ending November at 65% compared to Europe at 63%.

The world trajectory was clearly influenced by Asia, which showed serious vaccination administration starting in June, moving upward to nearly match Europe in October, then matching it in November at 63%. Africa remains far behind the others, though there is an encouraging upward movement beginning in July.

Because a majority of vaccines require two doses, we will likely see total doses expand more quickly in coming months, with full vaccination catching up at a rate dependent on supply, strategy and willingness of populations to cooperate.

Comparison of U.S. with other Countries

Cases

Raw numbers are virtually meaningless without relating them to the size of a given country, so looking at cases as a proportion of population helps get a sense of the relative impact.

France returns to the top-5 after being replaced by Argentina last month. The other four return, but shuffle their order significantly because of the surge of cases in Europe.

Over the 14 months shown in Figure

6A, the top-5 have crossed paths several times and ended October spread evenly, all well above the global level of 3.3%. Surges in Europe brought a remarkable ending to November, with Belgium, Netherlands, UK and USA all in a very tight cluster between 14.9% and 15.5%. Had USA surged like the other three, it would have been well ahead, but its more moderate gain moved it from number 1 the previous three months to number 4 in November. France, as well, showed a modest gain rather than the surge experienced by its neighbors, putting it in fifth place, a full three percent behind the others.

Another way to look at population proportion is the measure "1 in." The global figure of 3.3% means that 1 in 30 people in the world have been reported with COVID (and that only by official record keeping, not including any unreported and likely asymptomatic cases). For USA it remains 1 in

7. Netherlands and UK drop by one to also end November at 1 in 7. Belgium also drops a point, to 1 in 6. France stays at 1 in 9.

All five countries return from October, in the same order. All five have been at or below the global level since August.

Mexico and Ecuador criss-crossed last month, with Ecuador slowing and Mexico continuing on an accelerated path. In November, Mexico flattened its pace while Ecuador moved up, so both ended at 3.0%. Philippines, which was added to the list of monitored counties in August, moved upward, meeting India last month and moving ahead this month. India had a major surge in April and May, then slowed, with a bump in October not enough to keep it ahead of Philippines. As seen before, however, it is difficult to predict future direction from the small changes seen here. Indonesia, added to the list of monitored countries in July, remains the lowest of the 29 monitored countries by proportion of cases for its population and the only one still below 2%.

These countries represent a considerable spread in size, from India, the second largest country, to Ecuador, ranked number 67 of the 215 countries tracked by worldometers. For Ecuador, its 3.0% of population means that 1 in 34 have been reported as having had the COVID virus, for India it remains 1 in 40, and for Indonesia 1 in 64.

Because the size of countries makes the use of raw case numbers illusory, another measure I find helpful is the rate of change from month to month (Figure 6C). The focus of the selection is on recent changes, but the chart goes back to December 2020 to keep the surges of late 2020 in perspective.

For this chart, countries are selected based on the change over two-months (end of September to end of November for this report). Philippines and Turkey have been replaced by Belgium and Germany. USA, which appears in every report, remains below the top 5.

The overall trend (red line, reflecting global level) flattens as it drops, ending November at the low of 6%. (A polynomial trend line flexes as adjacent data points go up and down, so the leading edge of newest dates can change the shape of the curve as new months are added).

Overall, global levels were much higher from November 2020 through January 2021 (the highest period of surging cases as pointed out in Figure 1), as was the absolute variation between countries. Global levels remained over 10% through May, then has been at or below 10% since then.

Belgium has been below the global level of monthly change until its recent surge saw it increase 32% in November. Ukraine, added to the list of monitored countries in August, increased 18% in November, but its 21% in October put it in the top-5 of change over two months. Germany, not in the top-5 five even during previous surges, increased 27% in November. UK, like Ukraine, is in the top-5 because of significant increases in both October and November (16% and 13%). Netherlands, added to the list of monitored countries in August, saw a 23% increase in cases in November.