Making Information Make Sense

InfoMatters

Category: Information / Topics: History • Information • Statistics • Trends

COVID-19 Perspectives for January 2022

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: February 35, 2022

Omicron causes seismic surge in cases, raising the societal toll, but the good news is that mortality rates (deaths as proportion of cases) continue to fall&hellip'

Putting the COVID-19 pandemic in perspective (Number 19)

This monthly report was spawned by my interest in making sense of numbers that are often misinterpreted in the media or overwhelming in detail (some would say that these reports are too detailed, but I am trying to give you a picture of how the COVID pandemic in the United States compares with the rest of the world, to give you a sense of perspective).

These reports will continue as long as the pandemic persists around the world.

Report Sections:

• November-at-a-glance

• The Continental View • USA Compared with Other Countries

• COVID Deaths Compared to the Leading Causes of Death in the U.S.

• U.S. COVID Cases versus Vaccinations

• Profile of Monitored Continents & Countries • Scope of This Report

January-at-a-glance

Reminder: you can click on any of the charts to enlarge it. It will open in another tab or window. Close it to return here.

GLOBAL SNAPSHOT

COVID-19 not only continued to spread, but super-sized surges were obvious around the world. While the surge from the omicron variant in December focused on Europe, the impact in January was far more widespread, including USA. Fortunately, at least for now, deaths have remained far below and far more steady than cases. While many areas struggle to provide adequate health care, the proportion needing hospitalization is dropping.

Reports since the delta variant emerged in late summer 2021 continue to point to the high concentration of unvaccinated people among those requiring hospitalization. (In USA the CDC reports unvaccinated adults are 16 times more likely than fully vaccinated to need hospitalization.)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

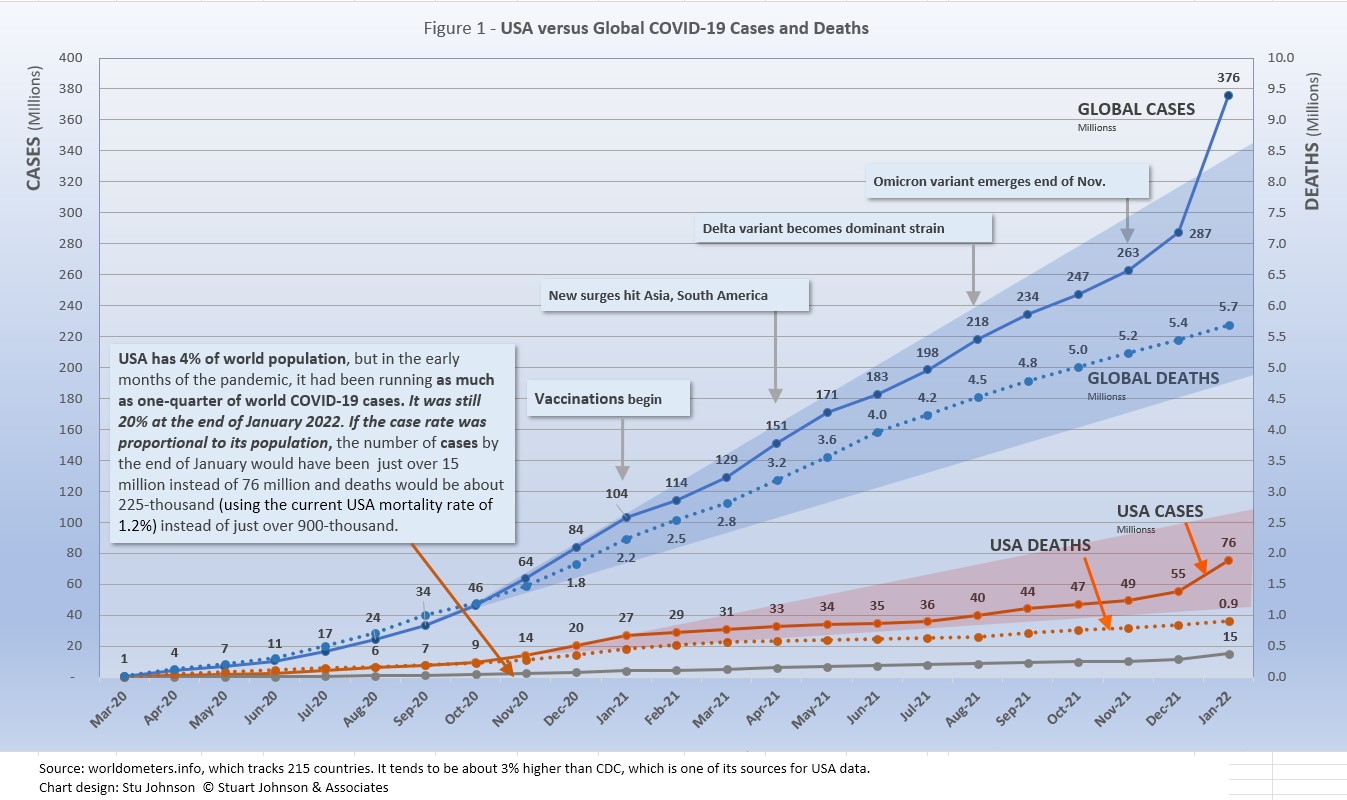

- Global CASES reached 375-million by the end of January, a 31% leap over December, which saw a 9% increase over November. That is a staggering increase in a single month as you'll see in the charts below. In a single month, the proportion of global population reported as being infected jumped from 3.6% to 4.8%, or nearly 89-million people worldwide.

The blue "cone" in Figure 1 above shows a possible high and low projection of global cases, with the bottom (roughly 170-million) representing the trajectory of the lower pace in late summer 2020 and the upper (approximately 335-million) representing a continuation of the major surge from November 2020 through January 2021. Even through the delta variant in recent months, the global increase in cases stayed inside the projection cone and was actually bending down some. Then came omicron, which hit Europe hard in December, bending the curve upward slightly before its nearly global spread in January blew the curve outside the projection cone by nearly 40-million cases.

- DEATHS from COVID around the world continued at the same pace as last month, up 4% to 5.7-million.

The pattern for global deaths tends to lag behind cases by weeks or months, but the global rate of increase continues to fall below that of cases—dropping from a 23% increase in January 2021 to 4% the last three months. While the curve for deaths is still rising overall, Figure 1 shows a noticeable slowdown in the last half of 2021, despite delta and omicron (though the sheer magnitude of omicron cases could bend the curve up in coming months).

- The need to QUARATINE has become far more common following the explosion of cases with omicron.

Where most of us who were vaccinated (and then boosted) made it through the delta variant with little impact, omicron has been different. As breakthrough infections or simply exposure to some who tested positive increased, caution tightened and the return to normalcy that had begun late is 2021 ground to a halt and even reversed. More people we know—most of them vaccinated and boosted and so far escaping COVID—had to quarantine following positive tests or exposure to someone known to be positive. While most suffered fairly mild symptoms, if any at all, the disruption to life has been considerable (and would have been far worse had it not been for the options many have to work from home).

Our church, which has been appropriately cautious throughout the pandemic, had been slowly moving back to "normal" in-person services with congregational singing (still through masks), when we suddenly did a livestream-only service on January 2,. While opened up since then with renewed attention to masking and distancing, many still choose to worship via the livestream option for now. Our pastor stayed away one Sunday; the food pantry where we volunteer—and where we've been requiring N95 masks for some time now—began to see volunteers pull back for a week or two because of the need to quarantine.

Schools that started the year with a return to in-person learning, have been forced to review a return to online or hybrid attendance. And it's obvious in stores and restaurants that service, which had declined significantly because of shifting employment patterns during the pandemic, was now impacted even more by workers who had to quarantine for a week or two.

So, while there is good news in the sense that deaths have not skyrocketed along with cases and government authorities have avoided tight lockdowns (which some European countries invoked during the Christmas holidays), the societal impact of the omicron variant has been significant.

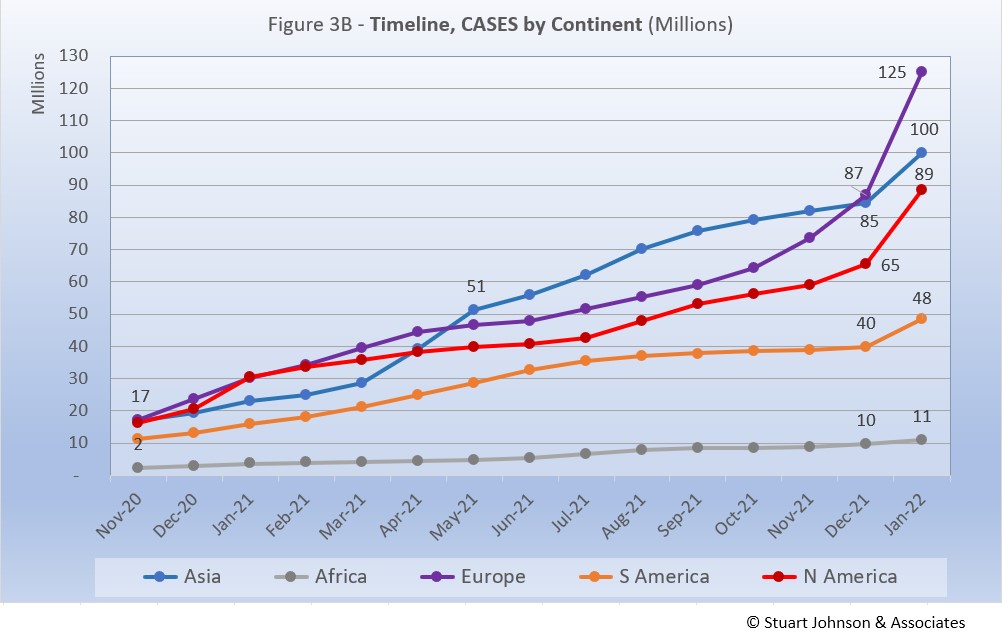

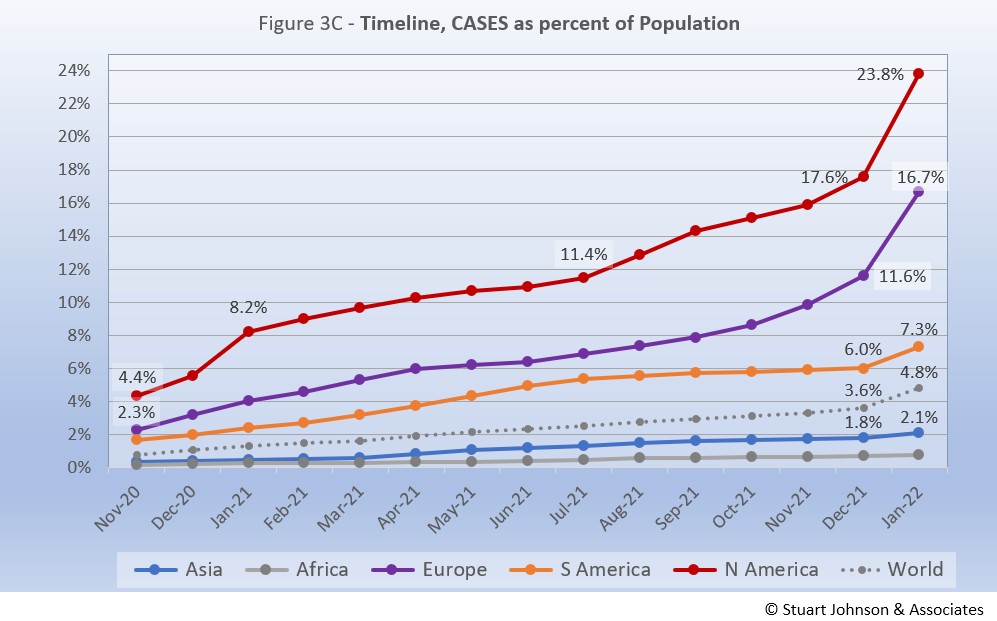

- BY CONTINENT. At the global level, omicron produced a noticeable but relatively small bend in the curve for cases as a proportion of population (Fig. 3C), because Asia and Africa—the two largest continents—barely budged. That was not the case with the other continents. South America, which had been slowing and nearly flat over the previous three months, bent upwards significantly in January. Europe and North America shot upward at a startling rate—Europe from 17.6% of its population reported having been infected by the end of December 2021 to 23.8% by the end of January 2022. North America was up from 11.6% to 16.7%.

- USA continues to lead the world in the number of reported cases and deaths, but also leads the world in the number of COVID tests and is respectable in vaccinations, but hampered by vaccine resistance.

USA cases soared 37% in January, to 75.6-million or nearly 23% of the population. However, four European countries now surpass USA in cases as a proportion of population (Figure 6A). The USA share of global cases had been trending down from a high of 25.9% in January 2021, to a low of 18.8% in November, but the omicron surge has pushed that back up to 20.1%.

Similarly, deaths have declined from 20.9% of the world total in September 2020 to 14.5% at the end of August 2021 before heading back up slightly through January. As you will see in details below, while USA outpaced everyone through the early months of the pandemic, the vast disparity was slowly shrinking even as the delta and omicron variants brought renewed surges in cases.

The red projection cone surrounding USA Cases in Figure 1 shows a pronounced flattening of the curve from January to July 2021 (vaccinations), with a very noticeable upward bend in August (delta variant among unvaccinated), another in December followed by a more significant surge in January (omicron variant among unvaccinated and "breakthrough" infections of vaccinated)—still well within the projection cone, which for USA extends from roughly 33- to 107-million. The upward bend for USA cases from August 2021 to January 2022 is clearly visible in Figure 1, but even more pronounced in Figure 10 below, which "zooms in" on USA. Figure 11 provides a detailed view of USA vaccination.

Figure 1 also shows how much lower cases in USA would be—approaching 15-million by now, instead of 76-million—if they were proportional to the global population. It would also mean about 225-thousand deaths instead of more than 900-thousand.

- THE OMICRON VARIANT emerged at the end of November and hit Europe hard, bringing back lockdowns and severe restrictions in several countries. In January the surge became turbo-charged and spread to North America and to a lesser but noticeable extent to South America. Compared to omicron, the delta variant that caused so much anxiety six months ago seems little more than a worn out speed bump. In fact, given all he attention given to delta, its impact is barely visible in Figure 1 (it may be more obvious in other charts because of differences in scale, but it obviously pales in comparison to omicron).

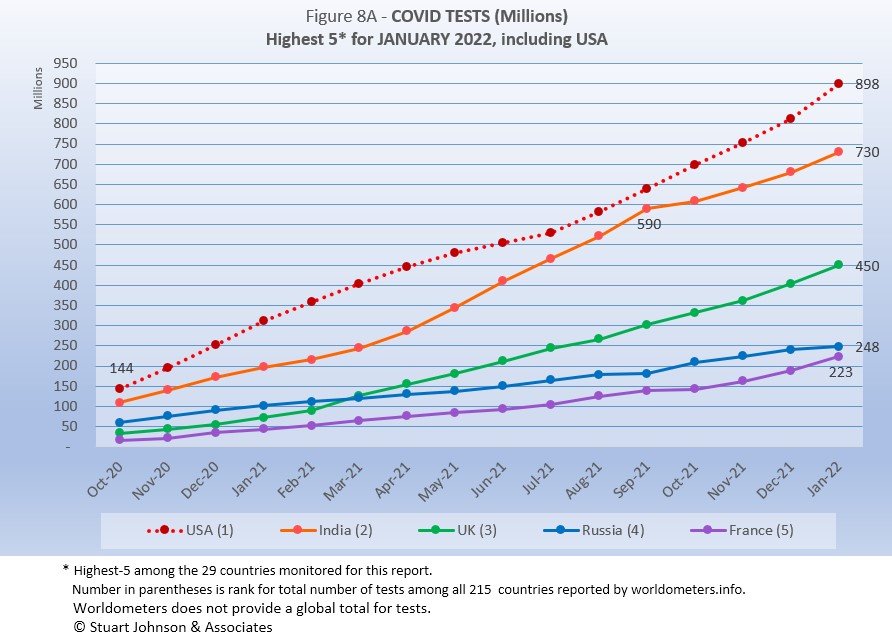

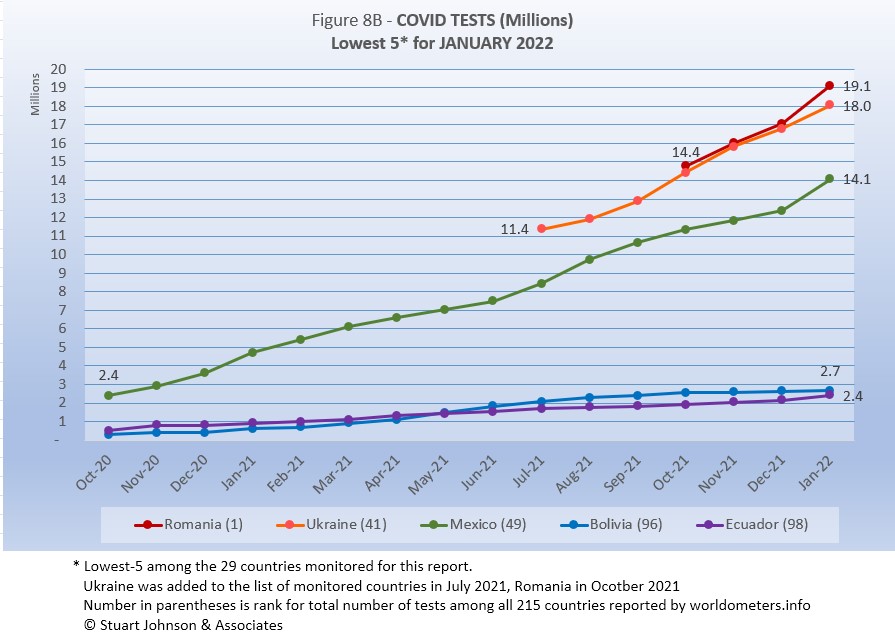

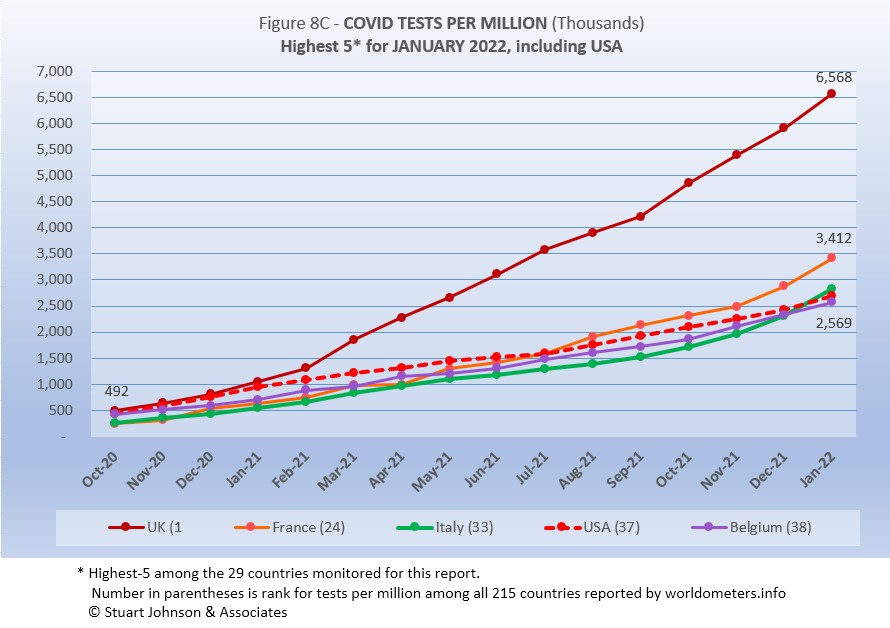

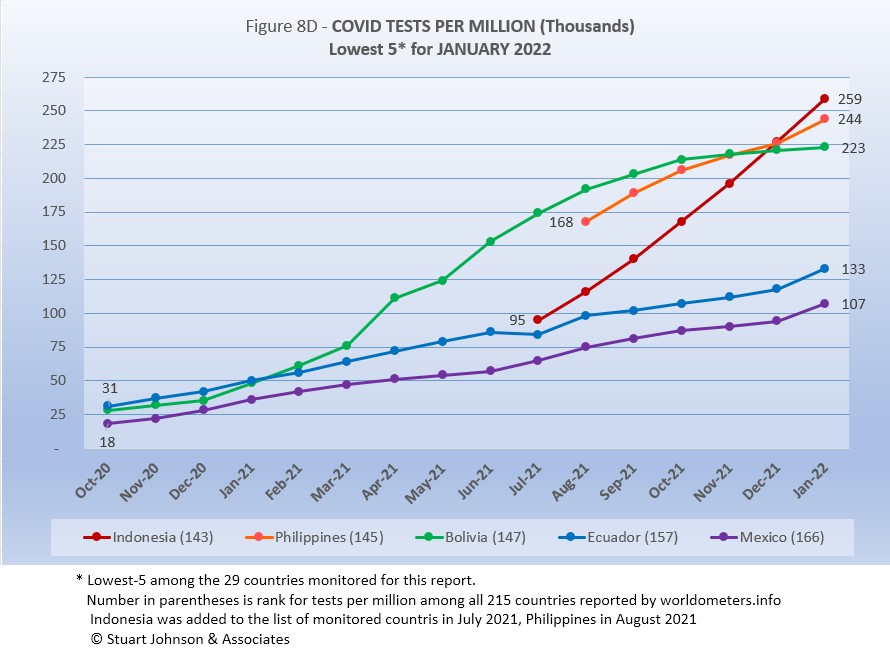

- TESTING. USA leads in the number of tests, with 898-million, followed by India, UK, Russia and France. Of the 29 countries monitored for this report, Romania, Ukraine, Mexico, Bolivia and Ecuador report the lowest number of tests. By proportion of population (tests-per-million), UK is far ahead of others, with the equivalent of more than 6 tests per person. USA is about 3 tests per person, similar to the other top countries. At the low end, the number of tests covers 25% or less of population. (See figures 8A, 8B, 8C, and 8D). Home tests will typically not be reported because there is no way of accurately recording them.

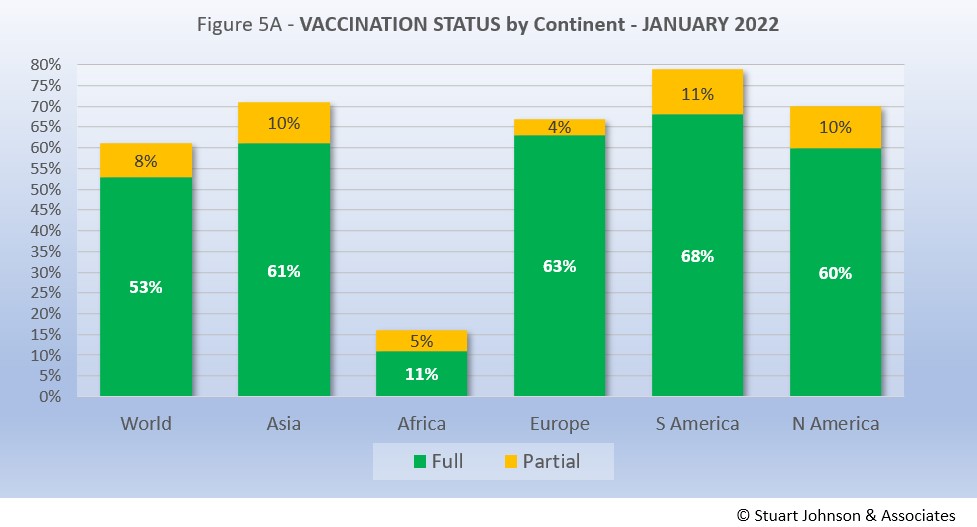

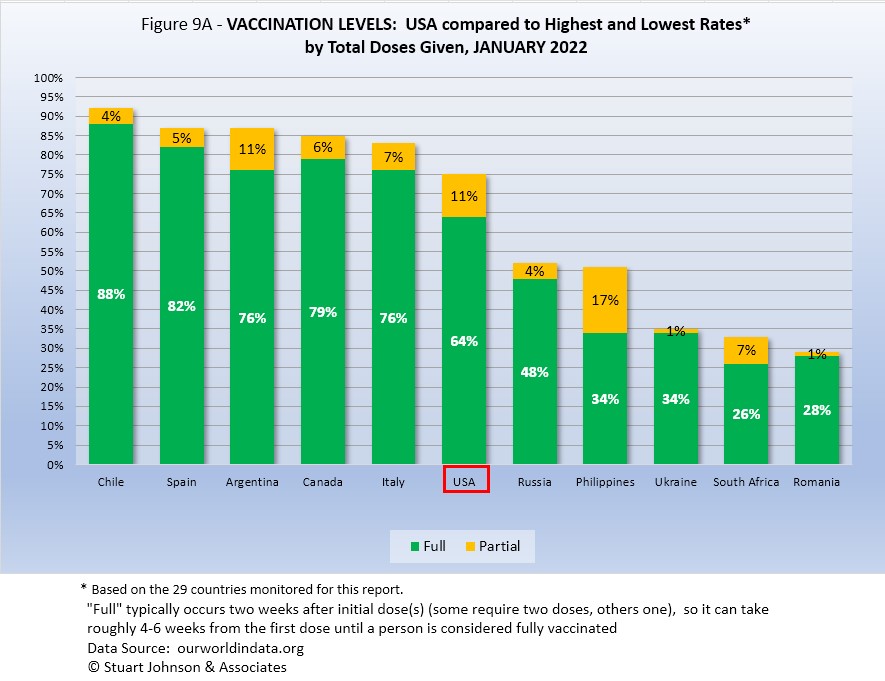

- VACCINATIONS. 61% of the world's population have been reported as receiving at least one dose of vaccine by the end of January. (See figures 5A, 5B, 5C, 9A, 9B and 11).

South America leads the world in vaccination, with Chile reporting 88% fully vaccinated. USA continues to move ahead, but slowly, with 64% fully vaccinated at the end of January (2% better than December) and another 11% partially vaccinated (no change).

- COUNTRIES TO WATCH. No countries have been added to the list of those that I monitor. The weekly comparison report on worldometers.info, however, gives a sense of hot spots to watch. Based on weekly activity, this includes Japan, Israel, Portugal, Australia, Denmark, Vietnam and Greece—all in the top 20 of new cases and/or deaths in the last week of January. While some of these have populations too small to make much of an impact on this report, they generally confirm (along with countries recently added to my monitored list) that the recent focus on Europe is broadening out again as omicron spread more widely.

Where you get information on COVID is important. In an atmosphere wary of misinformation, "news-by-anecdote" from otherwise trusted sources can itself be a form of misinformation. As I go through the statistics each month, I am reminded often that the numbers do not always line up with the impressions from the news. With that caveat, let's dig into the numbers for January 2022.

THE CONTINENTAL VIEW

The most obvious change in November is the surge in COVID cases in Europe. The other major continents either continued at their recent pace or slowed somewhat in growth of cases. Oceana is not included because of its small size, about one-half a percent of world population.

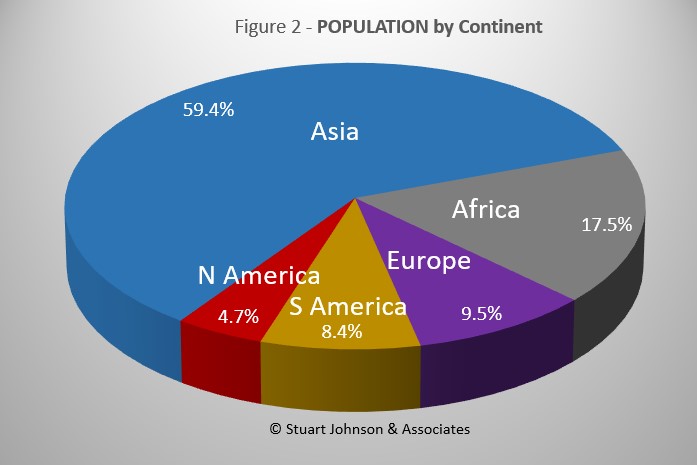

While COVID-19 has been classified as a global pandemic, it is not distributed evenly around the world.

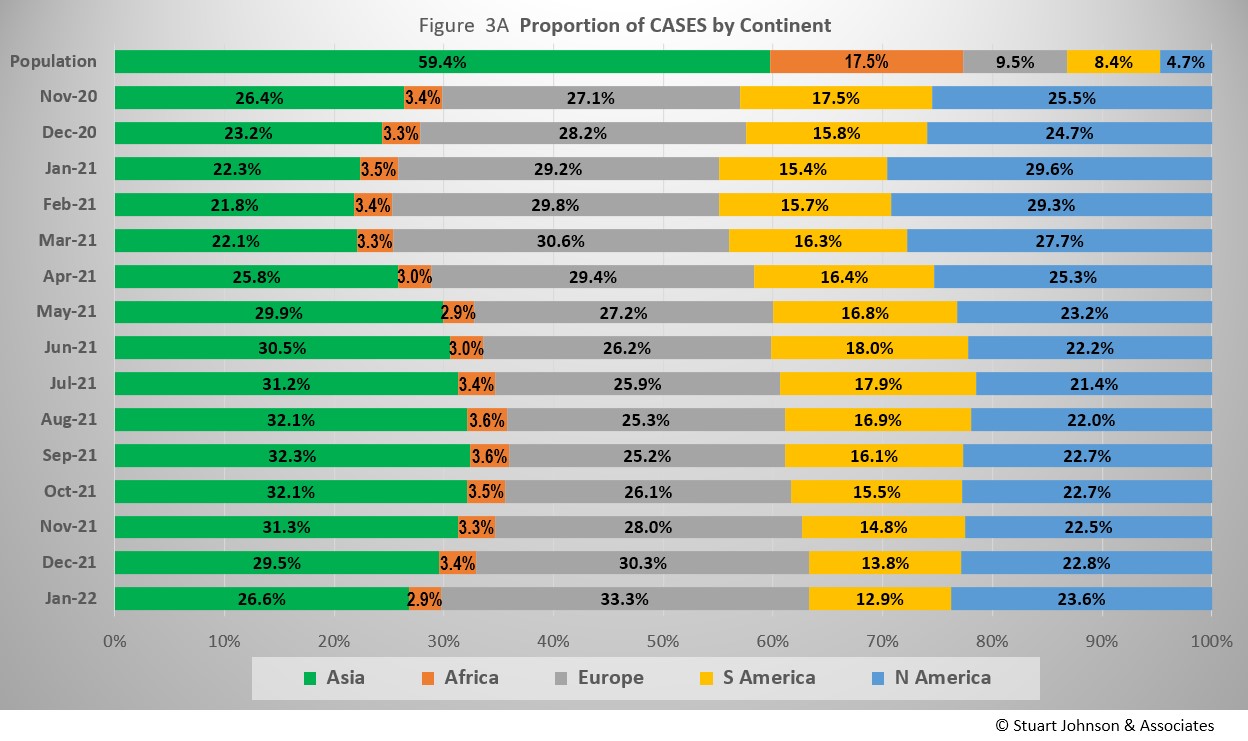

Asia accounts for 59.4% of the world's population (Figure 2), but had only 26.85% of COVID cases at the end of January (Figure 3A)—affecting a mere 2.1% of its population—down from a high of 32.3% in September. (COVID cases now represent 4.8% of world population).

The biggest trends in the proportion of cases among continents are most noticeable since March 2021:

- Asia - rising to a peak of just over 32% in September, then declining the last four months. Asia had a noticeable jump in cases in January because of omicron (Figure 3B), but as the largest continent by population it would take a far larger increase to make an impact on Figure 3A. Because of its vast size, even relatively large numerical gains in Asia can be offset by those in Europe and the Americas because we're looking here at the proportion of world cases.

- Europe - falling through September to just over 25% of world cases from a previous high of nearly 31% in March, Europe set a new high of 33.3% in January.

- North America - falling through July from a high of nearly 30% in January, then back up slightly, but remaining below 24% for the last five months

- South America - after peaking at 18% in June, steadily descending to just under its low of 13% in January

- Africa - hovering around 3.5%, then fell just below 3% in January.

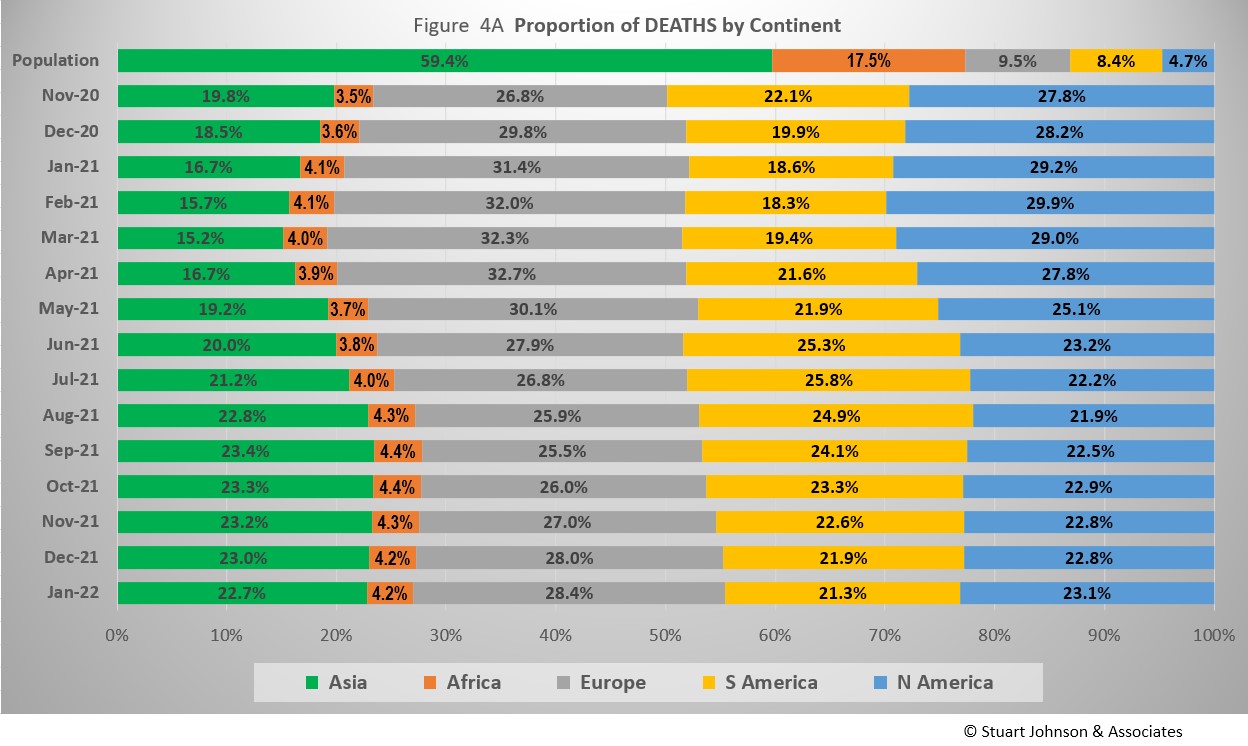

Where Asia and Africa combined represent about three-quarters (76.9%) of the world's 7.9-billion people, Europe, South America and North America still account for two-thirds of COVID cases (69.7% - Figure 3A) and about 7 in 10 of COVID deaths (72.8% - Figure 4A). The shares for Europe and North America were slowly coming down from their highs in February 2021 before moving back up each month since September because of delta and omicron. .

Omicron left no doubt that it was real and widespread in January.

In December, news reports gave the impression of widespread delta and omicron variant surges, but growth in the number of cases since July showed it was focused on Europe, followed to a lesser extent by North America. While Asia was ranked number 1 in November 2021, Europe edged past it in December with a significant upward turn over two months. North America also bent upward in December, then both Europe and North America took a sharp omicron-induced upward turn in January.

South America had nearly flattened in the last half of 2021, then had its own omicron surge in January—not as steep as Europe and North America, but very obvious. Asia was slowly accelerating through September before slowing slightly into December then had its own omicron surge in January.

Meanwhile, Africa remains far below the others with very minor changes from month to month.

The raw numbers of Figure 3B can be deceptive. Figure 3C gives a more realistic picture of the impact by translating raw case numbers to percentage of population. The shape of the curves is similar to those for raw numbers, but the order and spacing paints a different picture.

After a sharp increase in January 2021, North America slowed down for six months, before jumping 1.5 points to 13.0% in August, continuing that pace into September before slowing slightly. Then omicron hit, with a slight rise in December and a major surge to 23.8% in January.

Europe remains well below North America, though delta and omicron caused its proportion of cases to rise sharply from 7.9% in September to 11.6% in December and 16.7% in January. At the same time that Europe was trending upward, South America saw its curve flatten, rising only 0.6% since July, ending December at 6.0% of COVID cases in its population. Omicron hit South America, but with less intensity than experienced by North America and Europe, ending January with cases at 7.3% of population.

Asia and Africa, the two largest continents, remain at the bottom by proportion of COVID cases for their populations. Asia increased more noticeably than Africa between April and September, with a slight upturn in January representing what hardly looks like an omicron surge, ending at 2.1%. Africa's curve has been nearly flat, even through delta and omicron. In fact, it is the low proportions and huge populations of both Asia and Africa that have held the global curve to a nearly straight line progression until omicron bent it up in January, close to the rate of increase for South America, but far below that of North America and Europe.

The proportion of deaths between continents shows less extreme change than that for cases. In the early months of COVID, Europe and the Americas were growing in deaths, causing Asia to bottom out in its proportion of global deaths at 15.2% in March. The trends since then shadow those of cases, but lag behind by a month of two and are less extreme.

- Europe retains the highest proportion of COVID deaths at 28.4%, down from its high of nearly 33% in April, but steadily moving up since September—and still nearly three times its share of world population.

- North America remained steady for three months, then moved slightly ahead of Asia at 23.1% in January—five times its share of world population.

- Asia ended January at 22.7% of world COVID deaths, down one or two tenths of a percent each of the last five month. That is still well above its low just above 15% in March—and far below its 59% proportion of world population.

- South America has steadily dropped from a high of nearly 26% in July to 21.3% at the end of January and 2.5 times its share of world population.

- Africa has hovered around 4%, with the last five months inching up then down again, always far below its 17% share of world population.

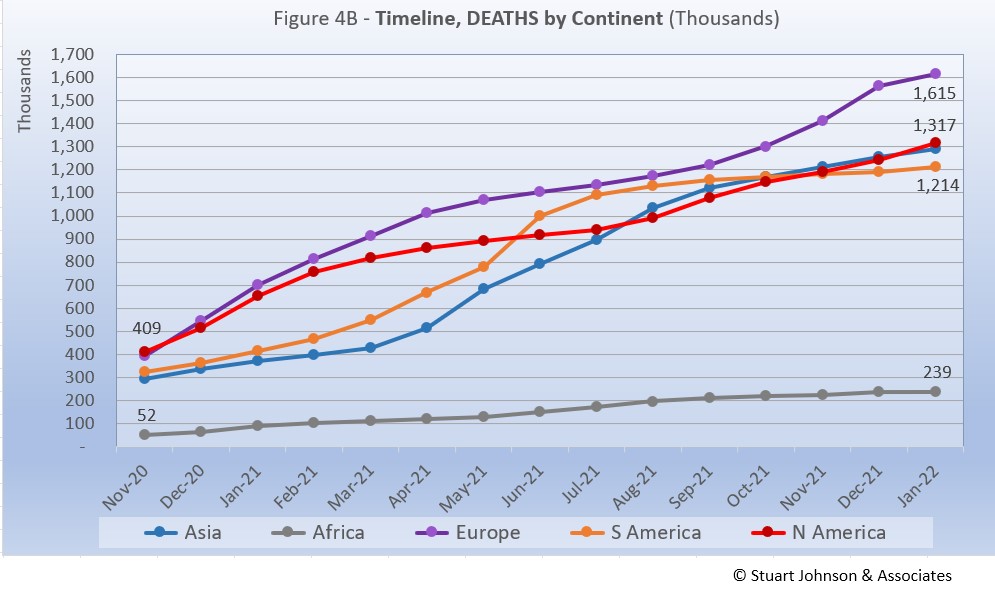

Deaths through January shows that while the trajectory lags behind cases and has progressed at a steadier rate, it does reflect the overall changes in Cases by continent. Except for Africa, which is well below the other continents in the number of COVID deaths, for the other four the 1-million milestone has been in the rear view mirror for months.

Europe remains at the top—and increased its lead due to the most obvious impact of the omicron variant—in number of deaths, at 1.6-million.

North America leveled off after vaccinations began in January, then started moving up again with the combination of vaccine resistance and both the delta and omicron variants.

Asia started to accelerate in May, on a path to join Europe, but started to slow in the last three months, tracking very close to North America in number of deaths. .

South America was headed toward passing Europe back in the first surge of 2021 then flattened and even though also impacted by delta and omicron, fell below North America and Asia in number of COVID deaths. .

Meanwhile, Africa progressed at a fairly steady pace, well below the others both in level and rate of change, despite being second in size, with 1.3-billion people.

Vaccinations

As Figure 5A shows, more than half of the global population has been reported as fully vaccinated (roughly 4.1-billion people), with another 8% having received the first of two doses. Given continuing gloomy reports in the news, those numbers may be surprisingly high given the monumental task of vaccinating multiple billions of people.

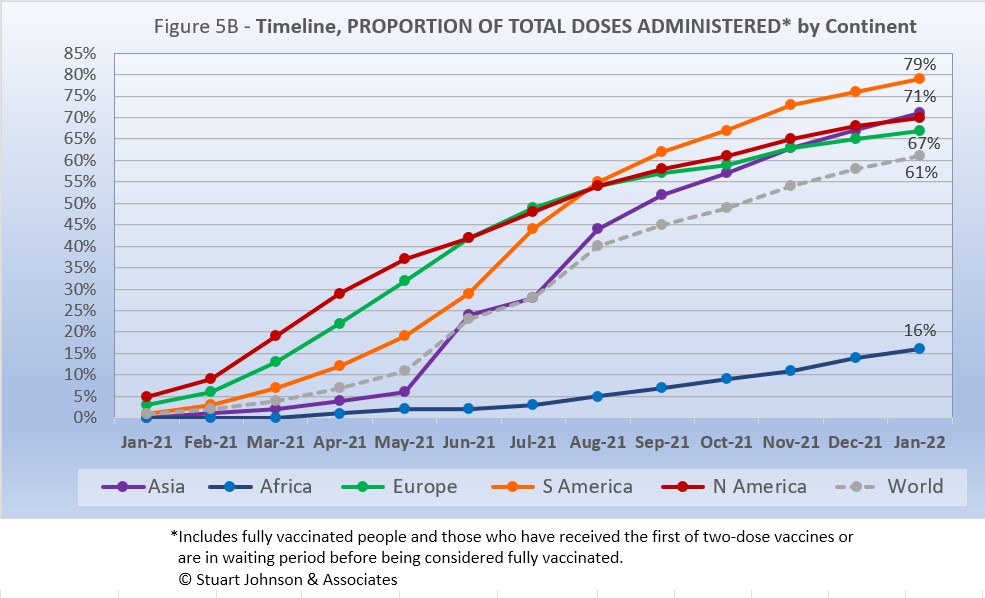

South America took the lead in total vaccinations in November (73%), and in December pulled away from Europe to have the highest rate of fully vaccinated as well, at 64%, moving up to 68% in January. Europe now reports 63% fully vaccinated, 67% total, followed by Asia (61% full, 71% total) and North America (60% full, 70% total).

Africa is well below the others, with 11% fully vaccinated and 16% total.

While South America got into vaccinations later and slower than North America and Europe, Figure 5B shows how it steadily pushed its way to the top of total vaccination doses administered by August, expanding its lead since then—and this by proportion of population, not raw numbers, so it's a fair comparison. Where North America started aggressively, it slowed in June as Europe and Asia caught up, with Asia barely ahead of North America at the end of January (71% vs 70%). Europe ended January at 67% of its population receiving at least one dose of vaccine.

The world trajectory was clearly influenced by Asia, which showed serious vaccination administration starting in June, moving upward to track closely with North America and Europe. Africa remains far behind the others, though there is an encouraging upward movement beginning in July.

COMPARISON OF USA WITH OTHER COUNTRIES

Cases

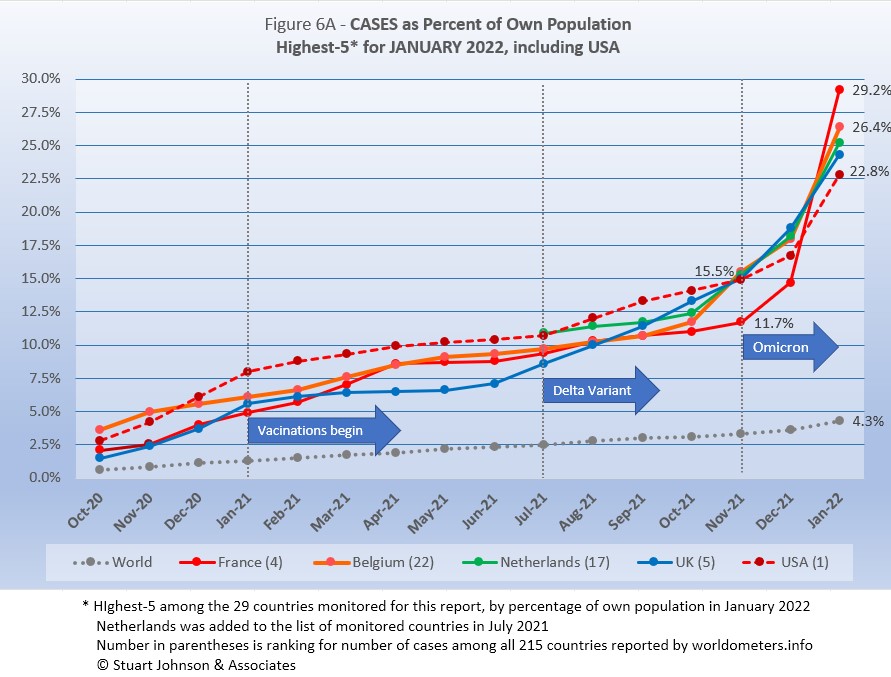

Raw numbers are virtually meaningless without relating them to the size of a given country, so looking at cases as a proportion of population helps get a sense of the relative impact. The countries with the greatest number of COVID cases illustrate how they represent an amplified view of what is barely noticeable in the world trend for cases (bottom line in Figure 6A),

The same five contrites have been in the top-5 for four months, only shifting in order. Before Netherlands joined the top-5 in August and UK in October, Spain, Argentina and Colombia (for one month in July) had been among the top-5 of cases as a proportion of population. .

While the beginning of vaccinations in January 2021 slowed the progression of COVID cases for the top-5 countries, the delta variant (in combination with large numbers still unvaccinated) brought with it a pronounced upward movement.

By the end of November, when the omicron variant had started to shut down Europe again, all but France had converged at roughly 15.5% of their populations having had contracted the virus. By January, France had shot up to nearly 3-in-10 of its population, USA with just over 2-in-10, while the global total has reached just over 4-in-100.

Another way to look at population proportion is the measure "1 in." The global figure of 4.8% means that 1 in 21 people in the world have been reported with COVID-19 since it began (and that only by official record keeping, not including any unreported and likely asymptomatic cases). For France it is now 1 in 3. for the remaining top-5 it is 1 in 4.

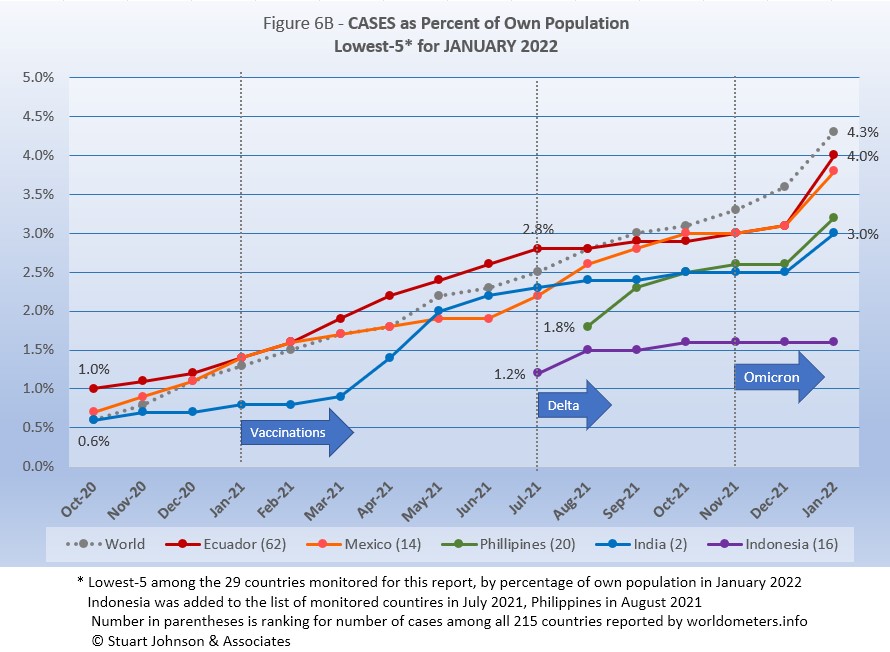

All five countries (of the 29 monitored) have been in the bottom-5 by proportion of population for five months, with Ecuador, Mexico and India in this chart every month since October 2020. Prior to September 2021, other countries in the bottom-5 were Bolivia, Iran, and Canada.

While the curve for World proportion appears to climb faster than in Figure 6A for the top-5, it is only became the scale of this chart is reduced, zooming in to make variations more apparent and seemingly larger. There is an interesting contrast with the top-5: because vaccination began later and remained lower for the bottom-5, cases continued to climb after January 2021 and seemed little affected by delta. But then, all except Indonesia showed a marked increase in January 2022 as the omicron variant spread around the world. (Compared to the previous chart, however, were this shown at the same scale, the rise in the bottom-5 would be a slight upward bend).

These countries represent a considerable spread in size, from India, the second largest country, to Ecuador, ranked number 67 of the 215 countries tracked by worldometers. For Ecuador, its 4.0% of population means that 1 in 25 have been reported as having had the COVID virus; for India it is 1 in 33, and for Indonesia 1 in 63.

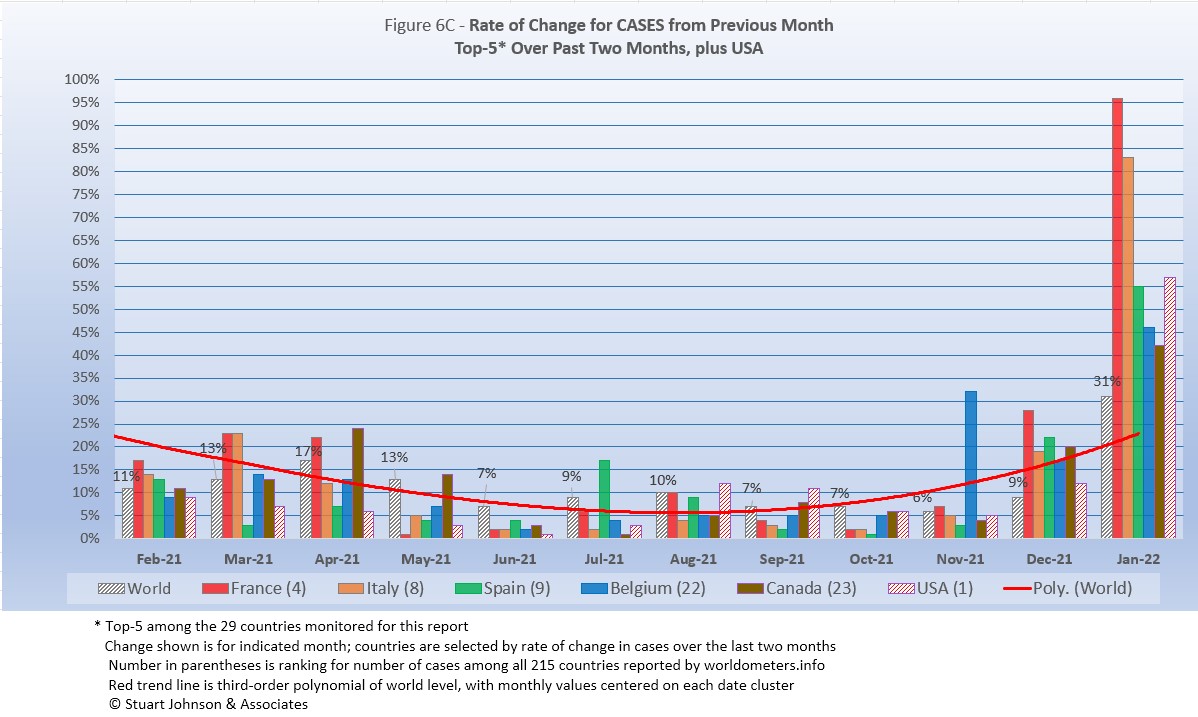

Because the size of countries makes the use of raw case numbers illusory, another measure I find helpful is the rate of change from month to month (Figure 6C). The focus of the selection is on recent changes, but the chart goes back to February 2021, following the first major surge and the beginning of vaccinations.

For this chart, countries are selected based on the change over two-months (end of November to end of January for this report). That produces a more varied "cast of characters" than other charts. For this chart, Spain, Italy, and Canada replace UK, Germany, and Netherlands. Only France and Belgium return from the last report. (See the chart below to see how the top-5 for changes in COVID cases have shifted around the world).

The overall trend (red line, reflecting global level) had been falling as the global level reached 6% (of change over the previous month) in November, but omicron pushed it back up to 31% by the end of January. (The trend line smooths out more rapid month-to-month changes).

Except for Belgium, which was significantly higher than the global level in November, the most radical departure from the global level of change for all five countries is in January 2022, with cases in France jumping by 90% over December, Italy by 83%, down to Canada at 42%. (USA is not included in the top-5 because that is based on change over two months, where it was 53% and the others were all above 60%).

| Month | Top-5 for Change in Cases Over 2 Months | Note | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2021 | India | Argentina | Turkey | Iran | Columbia | Asia surging |

| July 2021 | Colombia | Iran | Argentina | UK | Bolivia | South America surging |

| September 2021 | Iran | UK | Mexico | Turkey | USA | Delta peaking |

| November 2021 | Belgium | Ukraine | Germany | UK | Netherlands | Omicron strikes Europe |

| January 2022 | France | Italy | Spain | Belgium | Canada | Omicron spreads |

USA started well above the Global level from November 2020 (48%) through January 2021 (31%), then dropped to 9% in February after vaccinations had begun and the surge seemed to have ended (in USA anyway). From there it fell further below the global level each month until reaching a low of 1% in June. This has reversed, with a small bump in July that was still well below the global level. Then August and September saw the delta surge push USA over the global level again, but not by much. Then back below the global level of change for two months, followed in December by omicron, with USA cases increasing by 12%—well below the top 5, but back above the global level. In January 2022, up 57%—well above the 31% global change for January, but still out of the top-5 by change over the last two months.

Deaths

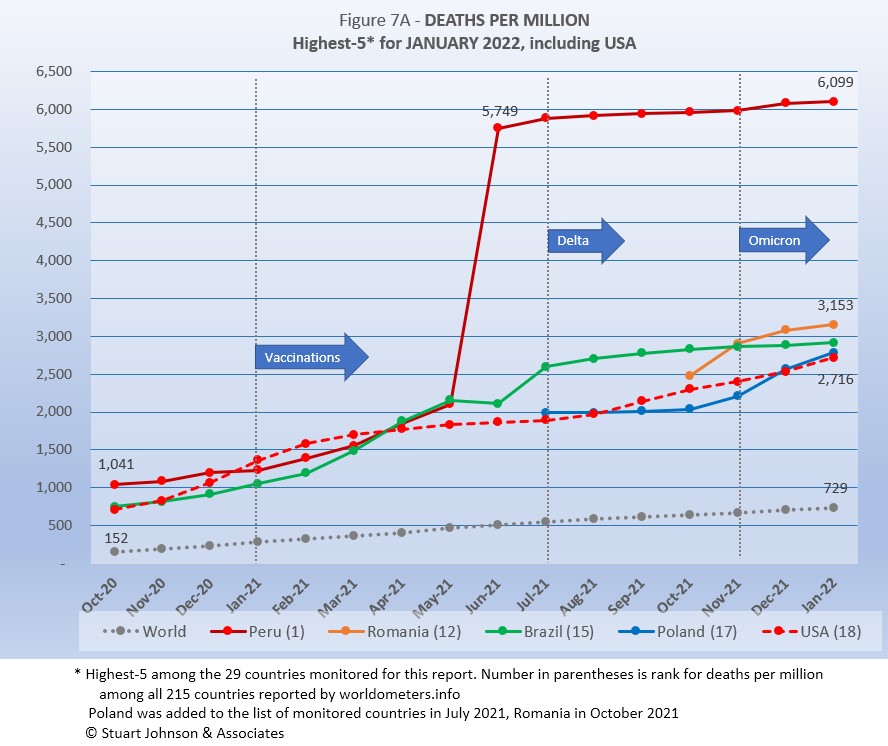

Because deaths as a percentage of population is such a small number, the "Deaths-per-Million" metric shown in Figure 7A provides a comparable measure.

USA replaces Argentina as one of the top-5 in deaths-per-million.

(USA was also in the top-5 in October 2021). The other four countries return from December. Brazil has been in the top-5 since May 2021, Peru since June. Romania and Poland have been in the top-5 since November. Other countries that have been in the top-5 include Belgium, UK, Italy, and Colombia.

As Figure 7A shows, Peru still soars over the others following a correction to its death data in June. January remains double #2 Romania and 8 times the Global level (coming down very slightly each month).

The January top-5 in deaths-per-million reflects the improving situation in South America—which dominated the top-5 starting in July and still had three countries in the top-5 in December— as omicron turned the focus to Europe and USA

USA rose steadily until evidence of the effectiveness of vaccination began to become evident with a slow down from March through July. It turned back upward in August, coinciding with the delta variant and vaccine resistance. As I suggested last month, USA was indeed on a track to return to the top-, which it did by surpassing Argentina in January.

Since this analysis focuses on 29 countries that have been in the top-20 of cases and deaths, there are 10 other countries not monitored with Deaths-per-Million between Peru, with a population of 33.5M, and Romania, with 19.1M. The largest are Bulgaria (6.9M, 4,878 Deaths-per-Million), Hungary (9.6M, 4,327), and Czechia (10.7M, 3,475).

All of the countries on the chart are well above the Global level, and (except for Peru) remain fairly close to each other.

While the delta variant was causing cases to rise, particularly in July and August, death rates in general remained unaffected or low in comparison—even South America, which had been the exception, began slowing down. This also seems to be true with the omicron variant, though we need another month or two to see if the massive rise in cases in January will produce a significant rise in deaths.

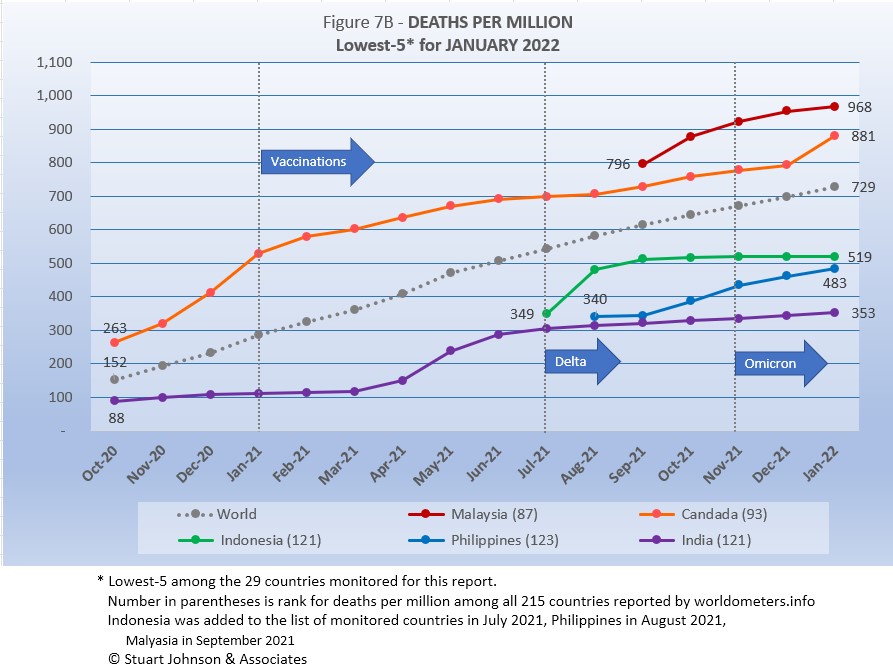

All five countries return from December, in the same order. Canada and India have been in the bottom-5 every month on this chart, Indonesia since August, Philippines since September, and Malaysia since December. Other countries that have been in the bottom-5 include Iran, Russia, Turkey, and Netherlands. .

The global curve shows a very steady growth against which the other countries can be compared. Malaysia and Philippines, both added to the list since July, showed a growth rate steeper than the global curve, with Malaysia slowing in January. Canada showed slowing growth around June, then began to grow again from August on, though at a slower pace than the global curve before being hit by omicron in January. Indonesia and India have flattened noticeably since September, despite delta and omicron.

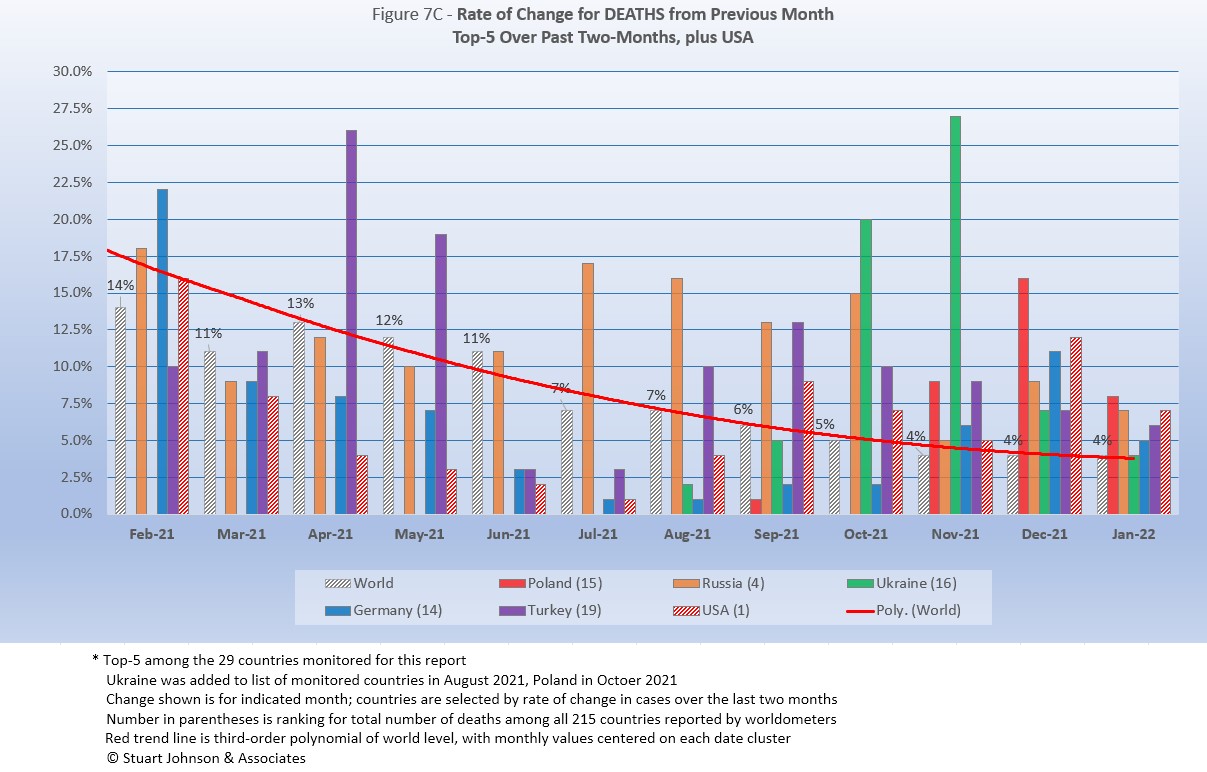

As with the comparable chart for Rate of Change for Cases (Figure 6C), countries for Rate of Change for Deaths (Figure 7C) are selected based on the change over two-months (end of October to end of December) in reported COVID deaths. The focus of the selection is on recent changes, but the chart goes back to February for perspective.

Germany and Turkey replace Romania and Philippines this month. See the chart below to see the changes in the top-5 countries over past months.

Unlike Figure 6C for Rate of Change for Cases, which dipped then rose again at the end because of omicron, the global trend (red line) for Rate of Change for Deaths continued on a downward path, and has been fixed at 4% over the previous month for three months now.

Because selection is based on change over two months, you can see that not only was change higher than the global level in December, but Ukraine was even higher in October and November. Russia, while still in the top-5, has come down considerably from July through October when it was well above the level of global change.

| Month | Top-5 for Change in Cases Over 2 Months | Note | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2021 | India | Turkey | Brazil | Colombia | Argentina | Tilt toward S America |

| July 2021 | Peru | Ecuador | Colombia | Argentina | Russia | South America surging |

| September 2021 | Indonesia | Iran | Russia | Turkey | Malaysia | Asia surging |

| November 2021 | Ukraine | Russia | Philippines | Turkey | Malaysia | Omicron beginning |

| January 2022 | Poland | Russia | Ukraine | Germany | Turkey | Omicron surging |

USA, (not in the top-5 by rate of change, but #1 in number of COVID deaths), started above the global rate of change in February, then fell below it through August, before starting to rise again, coinciding with the early success of vaccination followed by the impacts of delta and omicron.

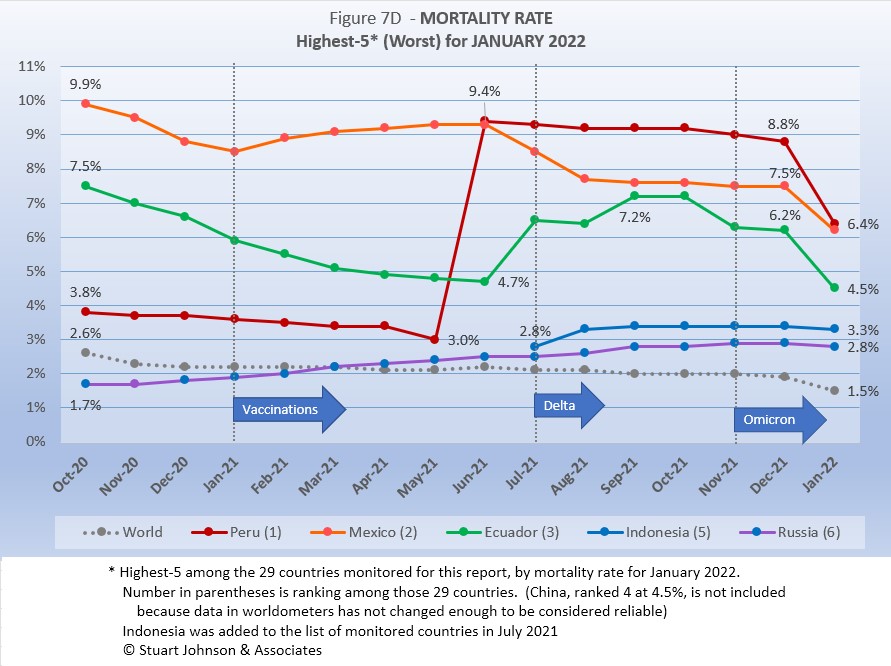

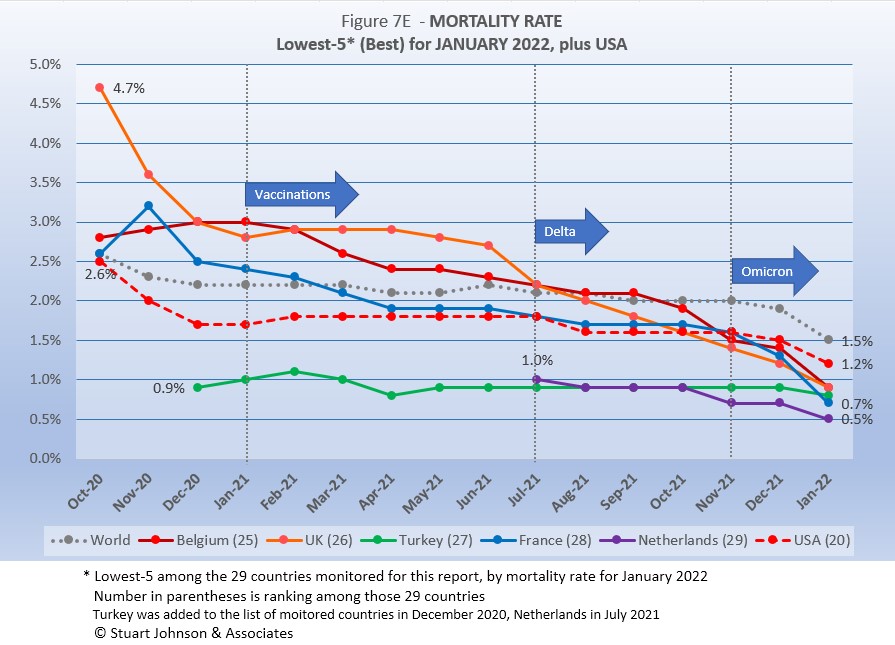

Mortality Rate

Mortality Rates (percentage of deaths against reported cases) have generally been slowly declining. This is not surprising as several factors came into play:

- In the early days of the pandemic, there was a high proportion of "outbreak" cases (nursing homes, retirement communities, other settings with a concentration of more vulnerable people). As the pandemic continued the ratio of "community spread" (with lower death rates) to "outbreaks" increased and the overall Mortality Rate went down.

- As knowledge about treatment increased, mortality went down.

- Since the death count is more certain (though not without inaccuracies), the side of the equation that can change the most is cases. As testing revealed more cases, the Mortality Rate would naturally go down because it would only affect cases and not deaths. In addition, the official numbers do not take into account a potentially higher number of people with the virus who are unreported and asymptomatic, so the real mortality rate could be even lower. (This will be a factor with availability now of home testing, where positives may escape official reporting).

- Vaccinations started in January 2021 and available in January 2022 will be the first anti-viral drug (though these should impact both cases and deaths).

- So far, the omicron variant has produced a huge spike in cases, but not in deaths (any increase could take another month or more), which is the reason the global mortality rate dropped so significantly in January 2022.

The Global mortality rate has dropped from 2.6% in October 2020 to 2.1% by April, where it stayed except for a bump back to 2.2% in June, before dropping again, reaching 1.9% in December, followed by a huge drop to 1.5% in January as noted above. The median for the countries monitored for this report has dropped from 4.8% in October 2020 to 2.8% for eight months, then down to 2.7% in December 2021 and 2.5% in January 2022.

Russia replaces Bolivia this month. Bolivia, along with the four returning from December, had all been in the top-5 since August. Italy was in the top-5 from May through July 2021 before being replaced by Indonesia. This is Russia's first time in the top-5.

Peru was in fourth place and declining until June 2021 when its corrected death numbers drove Mortality to 9.4%, just ahead of Mexico at 9.3%. Since then Peru slowly declined, ending December at 8.8% and took a significant omicron-induced drop to 6.4% in January as an upward swing in cases was not matched (yet) by a corresponding increase in deaths.

Mexico started with the highest mortality rate, 9.9%, went down then back up before making a more concerted decline in July, though it has leveled off for four months before taking its own omicron dip in January, to virtually tie with Peru.. Ecuador was on a steady path of dropping mortality rate through June, then has gone up more than Mexico went down, with the two looking like they would cross paths in August. However, both Mexico and Ecuador leveled off and were running on parallel tracks until Ecuador declined significantly in November, a little more in December and down to 4.5% from its omicron-related dive in mortality.

Indonesia was added to the list of monitored countries in July, coming in at #5, rising some in August, before going down slightly in January to 3.3%. Russia has seen rising mortality, very slow, but opposite the global trend. Like Indonesia, it saw a slight decline in January to end at 2.8%, still more than double the global rate of 1.2%.

Since these represent the best mortality rates, where low is good, the "rank" order is actually in reverse.

Belgium replaced Malaysia in January. Over time, the spread of mortality rates has become tighter, with all five, plus USA, below the global rate of 1.5%.Other countries in the best-5 have been India, Spain, Canada and Philippines, each for a month or two. The accelerated downturn attributed to the explosion of omicron case is evident for all curves on the chart, with France showing the biggest change and Turkey the least.

USA has been below the global level through the time covered by this chart. Starting at 2.5%, it quickly dipped to 1.7% by December 2020, rose to 1.8% for six months, then settled back to 1.6% for four months. It ended December at 1.5%, and dropped to 1.2% in January, ranking 20 among the 29 countries monitored (where lower rank represents better mortality), five places above Belgium. .

How real is the threat of death from COVID? That's where successful mitigation comes in. Worldwide, by the end of January, 1 in 21 people have been reported as having contracted COVID and 1 in 1,388 people have died. In USA, while the mortality rate is low, because the number of cases is so high, 1 in 365 have died through January 2022—between Poland (1 in 360) and Argentina (1 in 378). India has the lowest impact from death, with 1 death for every 2,708 people. Peru is the worst, at 1 in 160.

With low mortality, USA should have been able to keep deaths much lower, but the extraordinarily high number of cases means more deaths. Later in the report I will talk about countries that stress the importance of avoiding hospitalization, with the example of Denmark where cases have soared since delta and omicron but hospitalization and death remained very low. Even so, without a better-than-global mortality rate, the USA death rate would be far higher. Compared to the mortality rate during the 1918 pandemic, it could be ten times worse than it is. Even at the Global mortality rate of 1.5%, USA would have had just over 1.1-million deaths (out of 75.6-million cases) by the end of January, instead of just over 900-thousand with a mortality rate of 1.2%. As pointed out in Figure 1, however, if USA had cases closer to its proportion of world population, we would be looking at 225-thousand deaths out of 15-million cases. The response of the health care system and availability of vaccines are part of keeping mortality down.

Tests

The same five countries remain on top in COVID testings, having been in the same order since March 2021.

USA remains ahead of other countries in reported COVID tests administered, at 898-million, 23% ahead of India, widening the gap since September, but well below the 56% gap in April. UK continues at the pace it set in February 2021 (causing it to move into third place back in March 2021). Russia and France remain on paths of slower growth in raw numbers. At their current pace, France may surpass Russia he next report.

Since these are raw numbers, it is important to recognize the size of the country. It is also the case that COVID tests can be administered multiple times to the same person, so it cannot be assumed that USA has tested almost all of its population of some 331-million. Some schools and organizations with in-person gatherings are testing as frequently as once a week or more for those who are not yet fully vaccinated. That's a lot of testing!

Another wrinkle in the statistics for tests will be the increasing availability of home tests, where we may able to track sales but not tests administered since they are not like PCR and rapid tests offered by agencies that report testing to health authorities. While the statistics for tests have a degree of ambiguity, they are useful in showing the problem of equity, which is evident in the next chart.

The same five countries return in the same order they have been in for four months. Prior to that, other countries that have been in the lowest-5 have been Peru, Argentina, Belgium, South Africa and Netherlands. .

Romania, Ukraine and Mexico all show upward movement in tests while Bolivia and Ecuador remain at the bottom, both at lower rates of growth.

As questions arise about equity of testing between countries, check the number of tests for countries of similar size (within the 29 monitored countries):

- Mexico: 14.1M tests for 128.9M population, compared to Philippines: 27.3M tests for 109.6M population (1.9X the tests)

- Ukraine: 18.0M tests for 43.7M population, compared to Argentina: 32.5M tests for 45.7M population (1.8X)

- Peru: 23.3M tests for 33.0M population, compared to Malaysia: 44.6M tests for 32.4M population (1.9X)

- Ecuador: 2.4M tests for 17.6M population, compared to Netherlands: 21.1M tests for 17.1M population (8.8X)

- Bolivia: 2.7M tests for 11.7M population, compared to Belgium: 30.0M tests for 11.6M population (11.1X)

Tests per million adds another perspective. Fig. 8C shows the five countries with the highest tests per million. All five were in the same order from July through December 2021, then Italy moved to #3 in January 2022, passing USA and Belgium.

UK, already the most aggressive in testing, increased its numerical lead each month since February 2021, with a reported 6.6-million tests-per-million population in January, representing more than 6 tests per person. France maintained its #2 position, ending at 3.4-million tests-per-million, more than three tests per person. Italy moved into #3 with 2.8-million test-per-million, very close to USA with 2.7-million and Belgium with 2.6-million.

Anything over 1,000 (or "x-million tests-per-million") represents more tests than people (1,000 on the chart actually means 1,000,000), but as mentioned above, that does not mean that everyone had been tested. Some people have been tested more than once, and some are being tested regularly or with increased frequency.

The same five countries have appeared for six months, with the top three reversing order since November.

While Ecuador and Mexico have coasted along at roughly the same slow pace, the other three have mixed it up and increased their leader over the bottom two. Bolivia has been on the chart, along with Ecuador and Mexico, from the beginning. They tracked close to each other for several months before Bolivia began to accelerate in tests-per-million, continuing to climb until October when it slowed. This allowed Indonesia (added to the list of monitored countries in July) and Philippines (added in August) to catch up by December and then move ahead in January.

While improvement is evident in all five, the equivalent proportion of tests to population remains very low, from just under 11% for Mexico to 26% for Indonesia (and that would be reduced if some individuals receive more than one test). This illustrates the arguments over inequity in resources among countries.

Vaccinations

Figure 9A compares USA with the top-5 and bottom-5 of monitored countries by total doses administered. As you can see USA leans toward the upper countries, but its total vaccination rate of 75% is below the full vaccination rate for all of the top-5. On the other hand, USA is well ahead of the bottom five of the 29 monitored countries for either total doses or fully vaccinated.

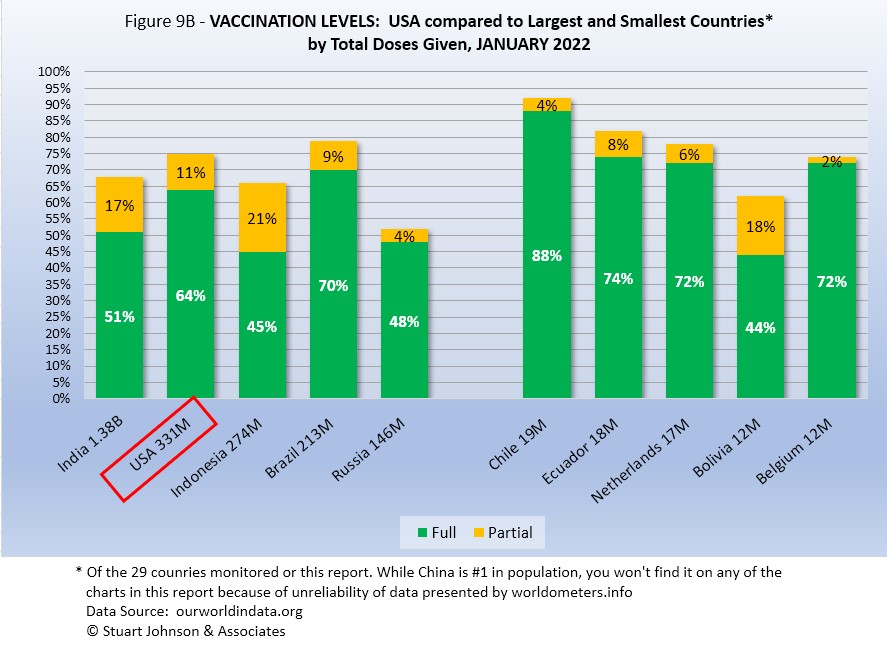

As pointed out in other parts of this analysis, Figure 9A does not tell the whole story. It's a bit of an apples and oranges comparison, with one major factor being the population of each country.

Taking population into account paints a different picture for USA compared to other monitored countries. In Figure 9B you see the five most populous countries on the left and the five smallest (of those monitored for this report) on the right. (China is not included because of unreliability of its data).

Brazil is ahead of USA in both full and total vaccinations. USA total vaccinations is ahead of India, Indonesia, and Russia, but full vaccinations beats only Russia's total vaccinations.

On the side of smallest countries, all except Bolivia are ahead of all five of the biggest countries in fully vaccinated. Chile is far ahead of all ten in total and fully vaccinated. Ecuador is three points better than Brazil in total vaccinations.

Thus, individual regions, provinces or states of the largest countries may be doing as well as some smaller countries, while the entire country lags behind the smaller ones.

CAUSES OF DEATH IN USA

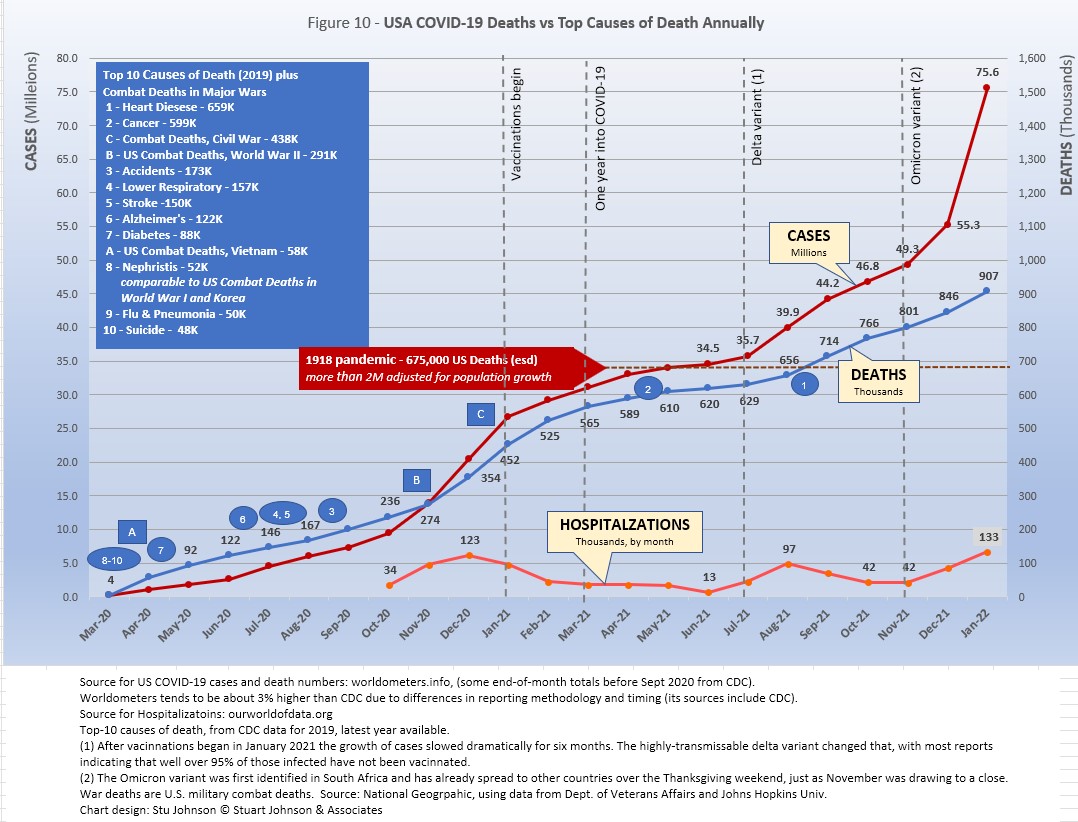

Figure 10 has been modified this month to accommodate the changing scale as cases roared ahead in January. This squeezed the location of timeline markers for the top-10 causes of death into the bottom of the chart, so a box was added to list the causes, with markers referencing them along the deaths (blue) curve.

Early in the reporting on COVID, as the death rate climbed in USA, a great deal of attention was given to benchmarks, most notably as it approached 58,000, matching the number of American military deaths in the Vietnam War. At that time, I wrote the first article in this series, "About Those Numbers," looking at ways of viewing the data, which at the time of that writing in May 2020 was still focused on worst-case models and familiar benchmarks, like Vietnam.

Three Critical Curves

Figure 10 shows the number of USA COVID cases and deaths against the top-10 causes of death as reported by CDC. That data reflects 2019 figures, the latest year available. More recently, I added a curve for hospitalizations, with data going back to October 2020.

Notice that for nearly nine months, the curve for deaths was increasing at a faster rate than cases. Then, starting in October 2020 the curve for cases took a decided turn upward, while deaths increased at a more moderate pace (the two curves use different scales, but reflect the relative rate of growth between them).

Unlike the case and death curves, which are cumulative, hospitalizations reflects the number of cases requiring hospitalization each month. You can see three peaks: the first with the initial surge (before vaccines became available) in December 2020, followed by August 2021 (delta) and January 2022 (omicron), which now represents the peak of hospitalizations. Notice, however, that the relative spread of cases-to-hospitalization is enormously different for omicron. In December of 2020, there were roughly 6.5-million new cases where January 2022 saw 20.3-million (a 212% increase), yet hospitalizations were only 11-thousand higher (8%).

Benchmarking the Numbers

Media reporting tended to focus on easily grasped benchmarks—deaths in Vietnam or World War II, or major

milestones like 500,000 (crossed in February 2021).

In August 2021 we passed the 2018 level for #1 heart disease (655-thousand), then passed it again in September when the 2019 data "moved the goal post" to 659-thousand. Another significant benchmark, pointed out in some news reports, was the 675-thousand estimate for deaths in USA during the 1918 pandemic. Adjusted for population growth, however, that number would now be around 2-mllion.

Having passed the annual death benchmarks and 1918 deaths, now we can only watch as the numbers continue to climb . . . .

The latest "Ensemble Forecast" from CDC suggests that by our next report we should see:

...the number of newly reported COVID-19 deaths will remain stable or have an uncertain trend over the next 4 weeks, with 7,600 to 23,700 new deaths likely reported in the week ending February 26, 2022. The national ensemble predicts that a total of 933,000 to 965,000 COVID-19 deaths will be reported by this date.

Note: As I've referenced in the notes for several charts that data from worldometers.info tends to be ahead of CDC and Johns Hopkins by about 3%, because of reporting methodology and timing. I use it as a primary source because its main table is very easy to sort and provides the relevant data for these reports. Such differences are also found in the vaccine data from ourworldindata. Over time, however, trends track with reasonable consistency between sources.

Perspective

The 1918-19 Spanish Flu pandemic is estimated to have struck 500 million people, 26.3% of the world population of 1.9-billion at that time. By contrast, we're now at 3.1% of the global population. Deaths a century ago have been widely estimated at between 50- and 100-million worldwide, putting the global mortality rate somewhere between 10 and 20-percent. It has been estimated that 675,000 died in the U.S.

IF COVID-19 hit at the same rate as 1918, we would see about 2-billion cases worldwide by the time COVID-19 is over, with the global population now at 7.9-billion—four times what it was in 1918. There would be 200- to 400-million deaths. The U.S. is estimated to have had 27-million cases (one-quarter of the population of 108-million) and 675,000 deaths. Today, with a population of 331-million (a three-fold increase from 1918) this would mean more than 80-million cases, and 2- to 4-million deaths.

However, at the present rate of confirmed cases and mortality while the total number of global cases could approach 500 million or more—comparable to 1918 in number—that would be one-quarter of 1918 when taking population growth into account . .. and assuming the pandemic persists as long as the Spanish Flu, which went on in three waves over a two year period. (We are facing entering a third year in March 2022). At the present rate of increase (close to 18.8-million cases per month) it would only take another 7 months to reach 500-million, roughly August of this year. That rate has accelerated as delta and omicron surges raised the case total significantly. The projected time to reach 500-million shrank about five months since my last report. Since omicron appears to be peaking, however, that rate could slow down, but we don't know what other variant may come along before COVID turns from pandemic to endemic.

If the total number of cases globally did approach 500-million, using the global mortality rate of 1.5% in January, there would be roughly 7.5-million deaths worldwide. Tragic but far below the number reported for 1918 (50-million) with an even wider gap (200 million) when taking population growth into account.

Earlier in the summer of 2021, I indicated that with vaccinations in progress and expected to be completed in the U.S. by the end of summer, the end of COVID-19 could come sooner. Like 1918, however, there have been major complicating factors, such as the combination of the delta and omicron variants with a high number of unvaccinated (ironically hitting hardest in Europe and USA where vaccines are readily available). While we may have thought the end of the pandemic was in sight, it is still too early to make predictions on the duration and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic globally. Indeed, when I commented on the curve for cumulative cases last month, said it looks like the trajectory of an airplane climbing toward cruising altitude. In January it looks more like a rocket headed toward outer space!

Despite the darkening forecast since delta and omicron, the vast difference in scale between the Spanish Flu pandemic a century ago and COVID-19 cannot be denied. Cases may be soaring but are behind 1918 when adjusted for population growth, and either way deaths are far below 1918 mortality. The key differences are the mitigation efforts, treatments available today (though still leaving the health care system overwhelmed in some areas during surges), the availability of vaccines and the first anti-viral drug for those recently infected.

In addition, in 1918 much of the world was focused on a brutal war among nations (World War I) rather than waging a war against the pandemic, which ran its course and was undoubtedly made much worse by the war, with trans-national troop movements, the close quarters of trench warfare, and large public gatherings supporting or protesting the war. While you will see pictures of police and others wearing masks during the 1918-19 pandemic, the need to promote the war effort and maintain morale took precedence over the kind of mitigation associated with major virus outbreaks since then, including COVID-19. Another factor clearly shown in the charts in these reports has been that the rate of increase in deaths has for some time now been well below the increase in cases, especially since vaccines became available in January 2021.

VACCINATIONS IN USA

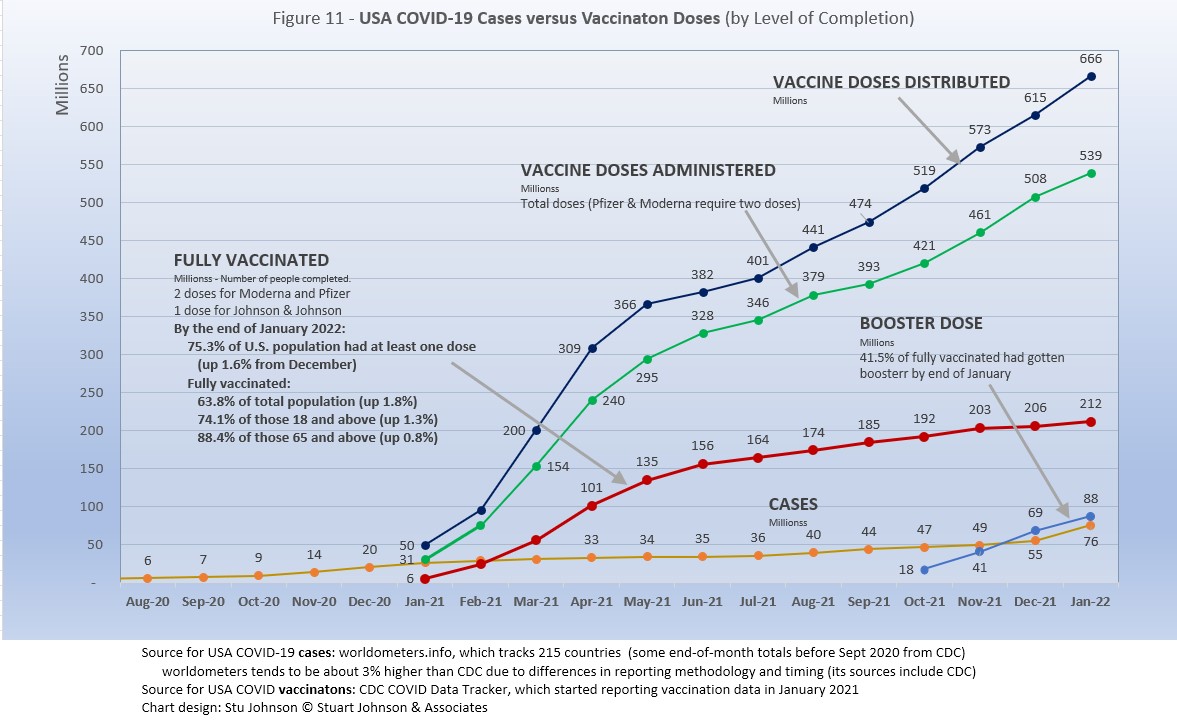

With remarkable speed (it usually takes years to develop vaccines), two COVID vaccines were granted emergency approval for use in USA starting in January 2021—the one by Pfizer requires super-cold storage, which limits its deployment. The other, by Moderna, requires cold storage similar to other vaccines. Both of these require two doses, which means that vaccine dosages available must be divided in two to determine the number of people covered. By March 2021 Johnson & Johnson had been granted approval for a single-dose vaccine. The numbers in Figure 11 represent the status of all three vaccines as of December 31 (as reported by CDC, which will be slightly different than ourworldindata data used in earlier vaccination charts). .

A person is considered "fully vaccinated" two weeks after the final (or only) vaccine dose; roughly five to six weeks total for Pfizer and Moderna and two weeks for Johnson & Johnson.

After a rapid start, vaccination slowed in late spring. Figure 11shows an upturn in Doses Distributed and Administered in August, a sign that perhaps the delta variant provided the impetus for increased vaccinations. The rate of increased distribution has continued into January. Doses Administered dipped slightly in September then recovered in October through November, then dipped again in January. The curve for Fully Vaccinated has increased fairly steady, but at a far lower rate than doses administered, meaning we're not closing the gap between partial and full vaccination (which increased by less than 2% in January).

Those getting boosters is up to nearly 88-million in three months, a third of those who are already fully vaccinated. In addition, in early November the CDC expanded vaccination approval for children ages 5-12 and in December the FDA approved the first anti-viral drug, Pfizer's Paxlovid. Despite that, USA fully vaccinated stands at 63%, not bad compared to other large countries, but well behind the best among the 29 countries monitored for this report (see Figures 9A and 9B above). The highest vaccination cohort in USA is those 65 and above, with 88% fully vaccinated.

Debates over masking policy and mandatory vaccination provides evidence that the real battle remains vaccination. A year ago we were debating lock-downs. Today the debate is how to be open but remain safe. Will the rise of infections and the call for more masking be enough to spur more vaccinations? For some, perhaps, but whether low levels of vaccinations have prolonged the pandemic (around the world) will be the subject of discussion and debate for years to come.

Vaccinating over 300 million people in the United States (much less a majority of the billions around the world) is a daunting task. It is a huge logistical challenge, from manufacture to distribution to administration. Yet, it is amazing that any of this is possible this soon after the identification of the virus just over 21 months ago—and that according to available data, more than half of the world's population of 9.8-billion have been at least partially vaccinated.

There is a delicate balance between maintaining hope with the reality that this is a huge and complicated logistical operation that takes time, with the prospect that COVID will be with us for some time—morphing from a global pandemic to an ongoing endemic like seasonal flu (more on this below)—partly because getting shots into the arms of the unvaccinated is proving to be a far bigger challenge than most officials assumed a few months ago.

As the richer countries with access to more resources make progress, the global situation is raising issues of equity and fairness within and between countries. Even as the U.S. and other countries launched large scale vaccine distribution to a needy world community, the immensity of the need is so great that a common refrain heard now is whether this aid is too little, too late. As COVID fades into a bad memory in countries able to provide help, will the sense of urgency remain high enough to produce the results needed to end this global pandemic?

Maintaining Perspective

In the tendency to turn everything into a binary right-wrong or agree-disagree with science or government, we ignore the need to recognize the nature of science and the fact that we are dealing with very complicated issues. So, in addition to recommending excellent sources like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it is also wise to consider multiple qualified sources.

While there has been much focus placed in trusting "the science," it is important to recognize that science itself changes over time based on research and available data. In the highly volatile political atmosphere we find ourselves in (not just in the U.S., but around the world), there is a danger of not allowing the experts to change their views as their own understanding expands, or of trying to silence voices of experts whose views are out of sync with "the science" as reported by the majority of media outlets.

In an earlier report, I mentioned the Greater Barrington Declaration, currently signed by more than 62-thousand medical & public health scientists and medical practitioners (and 863-thousand "concerned citizens"), which states "As infectious disease epidemiologists and public health scientists we have grave concerns about the damaging physical and mental health impacts of the prevailing COVID-19 policies, and recommend an approach we call Focused Protection."

For a personal perspective from a scholar and practitioner who espouses an approach similar to the Focused Protection of the Greater Harrington Declaration, see comments by Scott W. Atlas, Robert Wesson Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, in an article "Science, Politics, and COVID: Will Truth Prevail?"

Several months ago on SeniorLifestyle I posted an article by Mallory Pickett of The New Yorker, "Sweden's Pandemic Experiment," which provides a fair evaluation of the very loose protocols adopted by Sweden, essentially a variation of the "Focused Protection" approach. The "jury is still out" on this one, so judge for yourself whether Sweden hit the mark any better than the area in which you live.

UPDATE ON SWEDEN: As of early February, Sweden reported nearly 2.3-million cases of COVID, or 22.2% of its population of 10.2-million. There have been 16,142 deaths, for a mortality rate of 0.7%. Cases went up 64% over the previous month, but mortality fell 0.7%. Ranked 89 by population, Sweden was #34 in cases and #46 in deaths (up three ranks in cases and unchanged in deaths since last month). Hospitalizations rose 282% in January, from 519 to 1,994, compared to a 91% increase last month, 11% in November and a drop of 3% in October.

That puts Sweden even with USA in cases as a proportion of population (22.2%), with a mortality rate equal to France (0.7%), near the bottom (best) among the 29 countries monitored for this report and well below the global rate of 1.5%.

FROM PANDEMIC TO ENDEMIC: After posting last month's Perspectives, I posted on SeniorLifestyle an article by Sarah Zhang from The Atlantic, "America Has Lost the Plot on COVID." In it, she suggests that America (and the world) is headed not toward the eradication of COVID-19, but its transformation from pandemic to endemic, joining the seasonal flu as something we will deal with for some time. Getting there, she contends, is more a matter of mixed policy strategies than "following the science," but coming to grips with its inevitability could help lead to more effective strategies.

Zhang mentions Denmark as a counterpoint to what is happening in America, saying

One country that has excelled at vaccinating its elderly population is Denmark. Ninety-five percent of those over 50 have taken a COVID-19 vaccine, on top of a 90 percent overall vaccination rate in those eligible. (Children under 12 are still not eligible.) On September 10, Denmark lifted all restrictions. No face masks. No restrictions on bars or nightclubs. Life feels completely back to normal, says Lone Simonsen, an epidemiologist at Roskilde University, who was among the scientists advising the Danish government. In deciding when the country would be ready to reopen, she told me, “I was looking at, simply, vaccination coverage in people over 50.” COVID-19 cases in Denmark have since risen—under CDC mask guidelines, the country would even qualify as an area of “high” transmission where vaccinated people should still mask indoors. But hospitalizations are at a fraction of their January peak, relatively few people are in intensive care, and deaths in particular have remained low.

Crucially, Simonsen said, decisions about COVID measures are made on a short-term basis. If the situation changes, these restrictions can come back—and indeed, the health minister is now talking about that possibility. Simonsen continues to scrutinize new hospitalizations everyday. Depending on how the country’s transition to endemicity goes, it could be a model for the rest of the world.

UPDATE ON DENMARK: In early February, Denmark reported 1.7-million cases of COVID or 30% of its population of 5.8 million (another huge increase, from 8.5% and 497-thousand cases in November to 15% and 872-thousands cases in December). In spite of the explosion in cases, deaths increased by only 468 to 3,790, for a mortality rate of 0.2% (down 0.2% from last month). Ranked 113 in population, Denmark was #40 in cumulative cases and #91 in deaths (from #48 and #91 last month). Hospitalizations rose 45%, from 665 to 967, but that continues a downward trend in increases from 151% in October, to 78% in November and 61% in December, all following a 35% decline in September, opposite the dramatic rise in cases.

While Denmark's case-to-population proportion is more than 5 times the global rate of 4.8% and just above France (29%), its mortality rate is most striking, and the point of Zhang's observation about focusing on the prevention of hospitalization. The mortality rate (0.2%) is below Netherlands (0.5%), which is the lowest among the 29 monitored countries, and even further below the global rate of 1.5%. Does that mean that Denmark is actually a success? How do we interpret staggering surges in cases when hospitalization—and death—can be held at bay?

How we evaluate the many approaches used to deal with COVID will determine how we prepare for and approach the next global event—including what now appears to be a transition from pandemic to endemic for COVID-19.

My purpose in mentioning these sources is to recognize that there are multiple, sometimes conflicting, sometimes dissenting, voices that should be part of the conversation. The purpose of these monthly reports remains first and foremost to present the numbers about COVID-19 in a manner that helps you understand how the pandemic is progressing and how the U.S. compares to the world—and how to gain more perspective than might be gathered from the news alone.

Profile of Monitored Continents & Countries

(Data from worldometers.info).

| Rank | Country | Population | Share of World Population |

Density People per square km |

Urban Population |

Median Age |

| WORLD | 7.82B | 100% | -- | -- | -- | |

| Top 10 Countries by Population, plus Five Major Continents See lists of countries by continent |

||||||

| - | ASIA | 4.64B | 59.3% | 150 | 51 countries | 32 |

| 1 | China | 1.44B | 18.4% | 153 | 61% | 38 |

| 2 | India | 1.38B | 17.7% | 454 | 35% | 28 |

| - | AFRICA | 1.34BM | 17.1% | 45 | 59 countries | 20 |

| - | EUROPE | 747.7M | 9.6% | 34 | 44 countries | 43 |

| - | S AMERICA | 653.8M | 8.4% | 32 | 50 countries | 31 |

| - | N AMERICA | 368.9M | 4.7% | 29 | 5 countries | 39 |

| 3 | USA | 331.5M | 4.3% | 36 | 83% | 38 |

| 4 | Indonesia** | 274.5M | 3.5% | 151 | 56% | 30 |

| 5 | Pakistan* | 220.9M | 2.8% | 287 | 35% | 23 |

| 6 | Brazil | 212.9M | 2.7% | 25 | 88% | 33 |

| 7 | Nigeria* | 206.1M | 2.6% | 226 | 52% | 18 |

| 8 | Bangladesh* | 165.2M | 2.1% | 1,265 | 39% | 28 |

| 9 | Russia | 145.9M | 1.9% | 9 | 74% | 40 |

| 10 | Mexico | 129.3M | 1.7% | 66 | 84% | 29 |

| *these countries do not appear in the details because they have not yet reached a high enough threshold to be included **Indonesia was added to the monitored list in July 2021 Other Countries included in Analysis most have been in top 20 of cases or deaths |

||||||

| Rank | Country | Population | Share of World Population |

Density People per square km |

Urban Population |

Median Age |

| 13 | Philippines (2) | 109.6M | 1.4% | 368 | 47% | 26 |

| 17 | Turkey | 84.3M | 1.1% | 110 | 76% | 32 |

| 18 | Iran | 83.9M | 1.1% | 52 | 76% | 32 |

| 19 | Germany | 83.8M | 1.1% | 240 | 76% | 46 |

| 21 | United Kingdom | 67.9M | 0.9% | 281 | 83% | 40 |

| 22 | France | 65.3M | 0.8% | 119 | 82% | 42 |

| 23 | Italy | 60.4M | 0.8% | 206 | 69% | 47 |

| 25 | South Africa (1) | 59.3M | 0.8% | 94 | 67% | 28 |

| 29 | Colombia | 50.9M | 0.7% | 46 | 80% | 31 |

| 30 | Spain | 46.8M | 0.6% | 94 | 80% | 45 |

| 32 | Argentina | 45.2M | 0.6% | 17 | 93% | 32 |

| 35 | Ukraine (1) | 43.7M | 0.6% | 75 | 69% | 41 |

| 39 | Poland (1) | 37.8M | 0.5% | 124 | 60% | 42 |

| 39 | Canada | 37.7M | 0.5% | 4 | 81% | 41 |

| 43 | Peru | 32.9M | 0.4% | 26 | 79% | 31 |

| 45 | Malaysia (3) | 32.4M | 0.4% | 99 | 78% | 30 |

| 61 | Romania (4) | 19.1M | 0.2% | 84 | 55% | 43 |

| 63 | Chile | 19.1M | 0.2% | 26 | 85% | 35 |

| 67 | Ecuador | 17.6M | 0.2% | 71 | 63% | 28 |

| 69 | Netherlands (1) | 17.1M | 0.2% | 508 | 92% | 43 |

| 80 | Bolivia | 11.7M | 0.1% | 11 | 69% | 26 |

| 81 | Belgium | 11.6M | 0.1% | 383 | 98% | 42 |

(1) Added to the monitored list in July 2021 |

||||||

Scope of This Report

What I track

From the worldometers.info website I track the following Categories:

- Total Cases • Cases per Million

- Total Deaths • Deaths per Million

- Total Tests • Tests per Million (not reported at a Continental level)

- From Cases and Deaths, I calculate the Mortality Rate

Instead of reporting Cases per Million directly, I try to put raw numbers in the perspective of several key measures. These are a different way of expressing "per Million" statistics, but it seems easier to grasp.

- Country population as a proportion of global population

- Country cases and deaths as a proportion of global cases and deaths

- Country cases as a proportion of its own population

- Cases and deaths expressed as "1 in X" number of people

Who I monitor

My analysis covers countries that have appeared in the top-10 of the worldometers categories since September 2020. This includes most of the world's largest countries as well as some that are much smaller (see the chart in the previous section).

This article was also posted on SeniorLifestyle, which I edit

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: February 35, 2022 Accessed 4,861 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: Information / Topics: History • Information • Statistics • Trends

COVID-19 Perspectives for January 2022

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: February 35, 2022

Omicron causes seismic surge in cases, raising the societal toll, but the good news is that mortality rates (deaths as proportion of cases) continue to fall&hellip'

Putting the COVID-19 pandemic in perspective (Number 19)

This monthly report was spawned by my interest in making sense of numbers that are often misinterpreted in the media or overwhelming in detail (some would say that these reports are too detailed, but I am trying to give you a picture of how the COVID pandemic in the United States compares with the rest of the world, to give you a sense of perspective).

These reports will continue as long as the pandemic persists around the world.

Report Sections:

• November-at-a-glance

• The Continental View • USA Compared with Other Countries

• COVID Deaths Compared to the Leading Causes of Death in the U.S.

• U.S. COVID Cases versus Vaccinations

• Profile of Monitored Continents & Countries • Scope of This Report

January-at-a-glance

Reminder: you can click on any of the charts to enlarge it. It will open in another tab or window. Close it to return here.

GLOBAL SNAPSHOT

COVID-19 not only continued to spread, but super-sized surges were obvious around the world. While the surge from the omicron variant in December focused on Europe, the impact in January was far more widespread, including USA. Fortunately, at least for now, deaths have remained far below and far more steady than cases. While many areas struggle to provide adequate health care, the proportion needing hospitalization is dropping.

Reports since the delta variant emerged in late summer 2021 continue to point to the high concentration of unvaccinated people among those requiring hospitalization. (In USA the CDC reports unvaccinated adults are 16 times more likely than fully vaccinated to need hospitalization.)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Global CASES reached 375-million by the end of January, a 31% leap over December, which saw a 9% increase over November. That is a staggering increase in a single month as you'll see in the charts below. In a single month, the proportion of global population reported as being infected jumped from 3.6% to 4.8%, or nearly 89-million people worldwide.

The blue "cone" in Figure 1 above shows a possible high and low projection of global cases, with the bottom (roughly 170-million) representing the trajectory of the lower pace in late summer 2020 and the upper (approximately 335-million) representing a continuation of the major surge from November 2020 through January 2021. Even through the delta variant in recent months, the global increase in cases stayed inside the projection cone and was actually bending down some. Then came omicron, which hit Europe hard in December, bending the curve upward slightly before its nearly global spread in January blew the curve outside the projection cone by nearly 40-million cases.

- DEATHS from COVID around the world continued at the same pace as last month, up 4% to 5.7-million.

The pattern for global deaths tends to lag behind cases by weeks or months, but the global rate of increase continues to fall below that of cases—dropping from a 23% increase in January 2021 to 4% the last three months. While the curve for deaths is still rising overall, Figure 1 shows a noticeable slowdown in the last half of 2021, despite delta and omicron (though the sheer magnitude of omicron cases could bend the curve up in coming months).

- The need to QUARATINE has become far more common following the explosion of cases with omicron.

Where most of us who were vaccinated (and then boosted) made it through the delta variant with little impact, omicron has been different. As breakthrough infections or simply exposure to some who tested positive increased, caution tightened and the return to normalcy that had begun late is 2021 ground to a halt and even reversed. More people we know—most of them vaccinated and boosted and so far escaping COVID—had to quarantine following positive tests or exposure to someone known to be positive. While most suffered fairly mild symptoms, if any at all, the disruption to life has been considerable (and would have been far worse had it not been for the options many have to work from home).

Our church, which has been appropriately cautious throughout the pandemic, had been slowly moving back to "normal" in-person services with congregational singing (still through masks), when we suddenly did a livestream-only service on January 2,. While opened up since then with renewed attention to masking and distancing, many still choose to worship via the livestream option for now. Our pastor stayed away one Sunday; the food pantry where we volunteer—and where we've been requiring N95 masks for some time now—began to see volunteers pull back for a week or two because of the need to quarantine.

Schools that started the year with a return to in-person learning, have been forced to review a return to online or hybrid attendance. And it's obvious in stores and restaurants that service, which had declined significantly because of shifting employment patterns during the pandemic, was now impacted even more by workers who had to quarantine for a week or two.

So, while there is good news in the sense that deaths have not skyrocketed along with cases and government authorities have avoided tight lockdowns (which some European countries invoked during the Christmas holidays), the societal impact of the omicron variant has been significant.

- BY CONTINENT. At the global level, omicron produced a noticeable but relatively small bend in the curve for cases as a proportion of population (Fig. 3C), because Asia and Africa—the two largest continents—barely budged. That was not the case with the other continents. South America, which had been slowing and nearly flat over the previous three months, bent upwards significantly in January. Europe and North America shot upward at a startling rate—Europe from 17.6% of its population reported having been infected by the end of December 2021 to 23.8% by the end of January 2022. North America was up from 11.6% to 16.7%.

- USA continues to lead the world in the number of reported cases and deaths, but also leads the world in the number of COVID tests and is respectable in vaccinations, but hampered by vaccine resistance.

USA cases soared 37% in January, to 75.6-million or nearly 23% of the population. However, four European countries now surpass USA in cases as a proportion of population (Figure 6A). The USA share of global cases had been trending down from a high of 25.9% in January 2021, to a low of 18.8% in November, but the omicron surge has pushed that back up to 20.1%.

Similarly, deaths have declined from 20.9% of the world total in September 2020 to 14.5% at the end of August 2021 before heading back up slightly through January. As you will see in details below, while USA outpaced everyone through the early months of the pandemic, the vast disparity was slowly shrinking even as the delta and omicron variants brought renewed surges in cases.

The red projection cone surrounding USA Cases in Figure 1 shows a pronounced flattening of the curve from January to July 2021 (vaccinations), with a very noticeable upward bend in August (delta variant among unvaccinated), another in December followed by a more significant surge in January (omicron variant among unvaccinated and "breakthrough" infections of vaccinated)—still well within the projection cone, which for USA extends from roughly 33- to 107-million. The upward bend for USA cases from August 2021 to January 2022 is clearly visible in Figure 1, but even more pronounced in Figure 10 below, which "zooms in" on USA. Figure 11 provides a detailed view of USA vaccination.

Figure 1 also shows how much lower cases in USA would be—approaching 15-million by now, instead of 76-million—if they were proportional to the global population. It would also mean about 225-thousand deaths instead of more than 900-thousand.

- THE OMICRON VARIANT emerged at the end of November and hit Europe hard, bringing back lockdowns and severe restrictions in several countries. In January the surge became turbo-charged and spread to North America and to a lesser but noticeable extent to South America. Compared to omicron, the delta variant that caused so much anxiety six months ago seems little more than a worn out speed bump. In fact, given all he attention given to delta, its impact is barely visible in Figure 1 (it may be more obvious in other charts because of differences in scale, but it obviously pales in comparison to omicron).

- TESTING. USA leads in the number of tests, with 898-million, followed by India, UK, Russia and France. Of the 29 countries monitored for this report, Romania, Ukraine, Mexico, Bolivia and Ecuador report the lowest number of tests. By proportion of population (tests-per-million), UK is far ahead of others, with the equivalent of more than 6 tests per person. USA is about 3 tests per person, similar to the other top countries. At the low end, the number of tests covers 25% or less of population. (See figures 8A, 8B, 8C, and 8D). Home tests will typically not be reported because there is no way of accurately recording them.

- VACCINATIONS. 61% of the world's population have been reported as receiving at least one dose of vaccine by the end of January. (See figures 5A, 5B, 5C, 9A, 9B and 11).

South America leads the world in vaccination, with Chile reporting 88% fully vaccinated. USA continues to move ahead, but slowly, with 64% fully vaccinated at the end of January (2% better than December) and another 11% partially vaccinated (no change).

- COUNTRIES TO WATCH. No countries have been added to the list of those that I monitor. The weekly comparison report on worldometers.info, however, gives a sense of hot spots to watch. Based on weekly activity, this includes Japan, Israel, Portugal, Australia, Denmark, Vietnam and Greece—all in the top 20 of new cases and/or deaths in the last week of January. While some of these have populations too small to make much of an impact on this report, they generally confirm (along with countries recently added to my monitored list) that the recent focus on Europe is broadening out again as omicron spread more widely.

Where you get information on COVID is important. In an atmosphere wary of misinformation, "news-by-anecdote" from otherwise trusted sources can itself be a form of misinformation. As I go through the statistics each month, I am reminded often that the numbers do not always line up with the impressions from the news. With that caveat, let's dig into the numbers for January 2022.

THE CONTINENTAL VIEW

The most obvious change in November is the surge in COVID cases in Europe. The other major continents either continued at their recent pace or slowed somewhat in growth of cases. Oceana is not included because of its small size, about one-half a percent of world population.

While COVID-19 has been classified as a global pandemic, it is not distributed evenly around the world.

Asia accounts for 59.4% of the world's population (Figure 2), but had only 26.85% of COVID cases at the end of January (Figure 3A)—affecting a mere 2.1% of its population—down from a high of 32.3% in September. (COVID cases now represent 4.8% of world population).

The biggest trends in the proportion of cases among continents are most noticeable since March 2021:

- Asia - rising to a peak of just over 32% in September, then declining the last four months. Asia had a noticeable jump in cases in January because of omicron (Figure 3B), but as the largest continent by population it would take a far larger increase to make an impact on Figure 3A. Because of its vast size, even relatively large numerical gains in Asia can be offset by those in Europe and the Americas because we're looking here at the proportion of world cases.

- Europe - falling through September to just over 25% of world cases from a previous high of nearly 31% in March, Europe set a new high of 33.3% in January.