Making Information Make Sense

InfoMatters

Category: General / Topics: Censorship • Change • Demographics • Ethics • Government • Information • Information Management • Internet • Media • Opinion research • Policy • Science & Technology • Social Movements • Trends

Trust

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: March 65, 2018

Can we stop the downward slide?…

Back in May of 2015, I wrote on the issue of trust in an article, “Who Do You Trust?,” making reference to the TV game show by that name, which ran from 1958 to 1962. It was interesting to review that article myself, considering some issues that have appeared in the news since then. Given current circumstances and spurred by a couple of books I’ve been reading recently, it seemed to be a good time to return to the topic of trust.

America’s declining confidence in social institutions

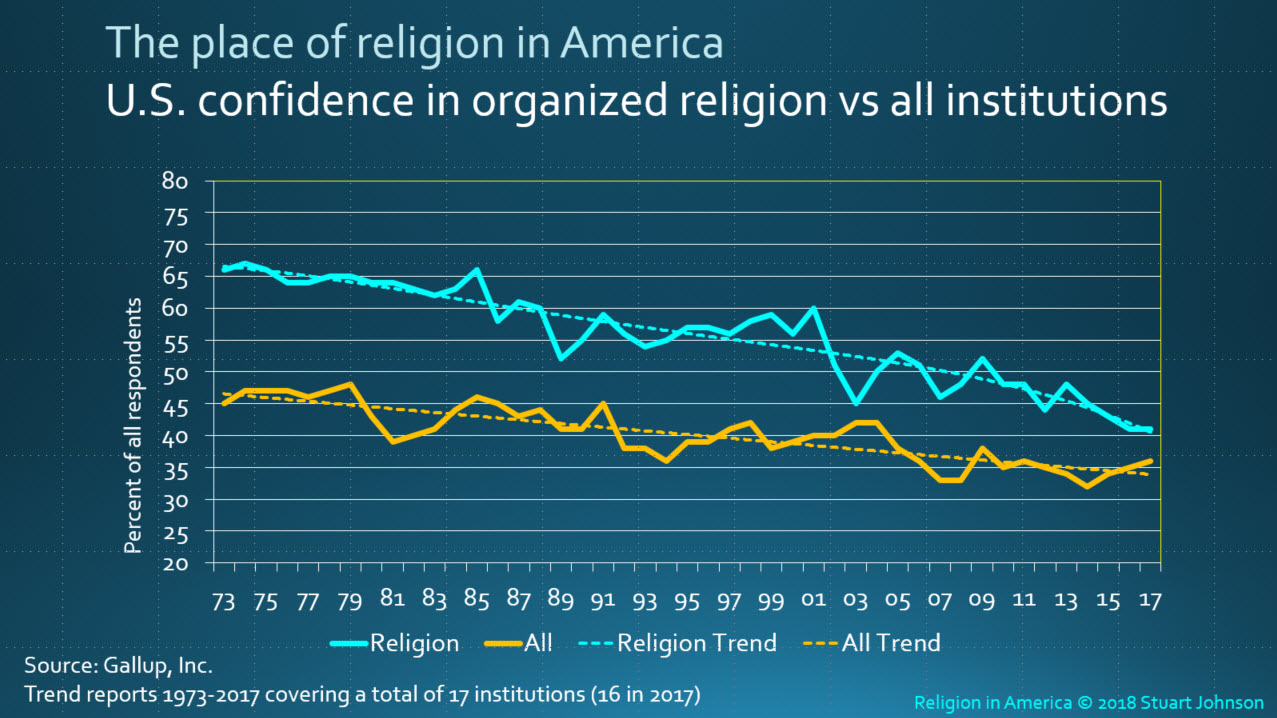

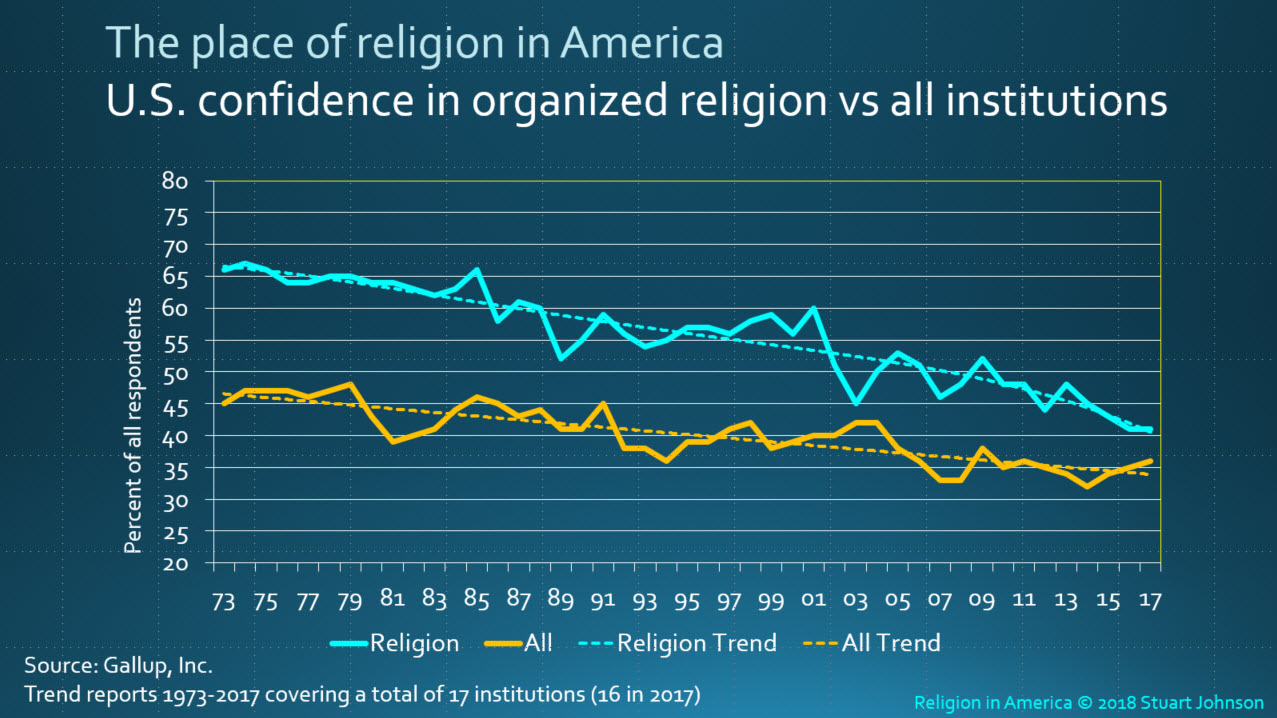

Research by the Gallup organization since 1973 shows a steady decline in the confidence of Americans in our major social institutions. For the purposes of this article, it seems fair to equate the term “trust” with “confidence,” the word Gallup uses in soliciting opinions. The chart below comes from my report on Religion in America, so it shows how organized religion compares to all institutions included in the survey (16 in 2017).

The data on this and the following chart represent selection of either a “Great deal” or “Quite a lot” of confidence,

representing the top two scores on a five-point rating scale, from “Great deal” to “None.”

While the drop in organized religion is significant, it is the general decline for all institutions over more than four decades that is central to my point here. (You can read more analysis on organized religion in my Religion in America report).

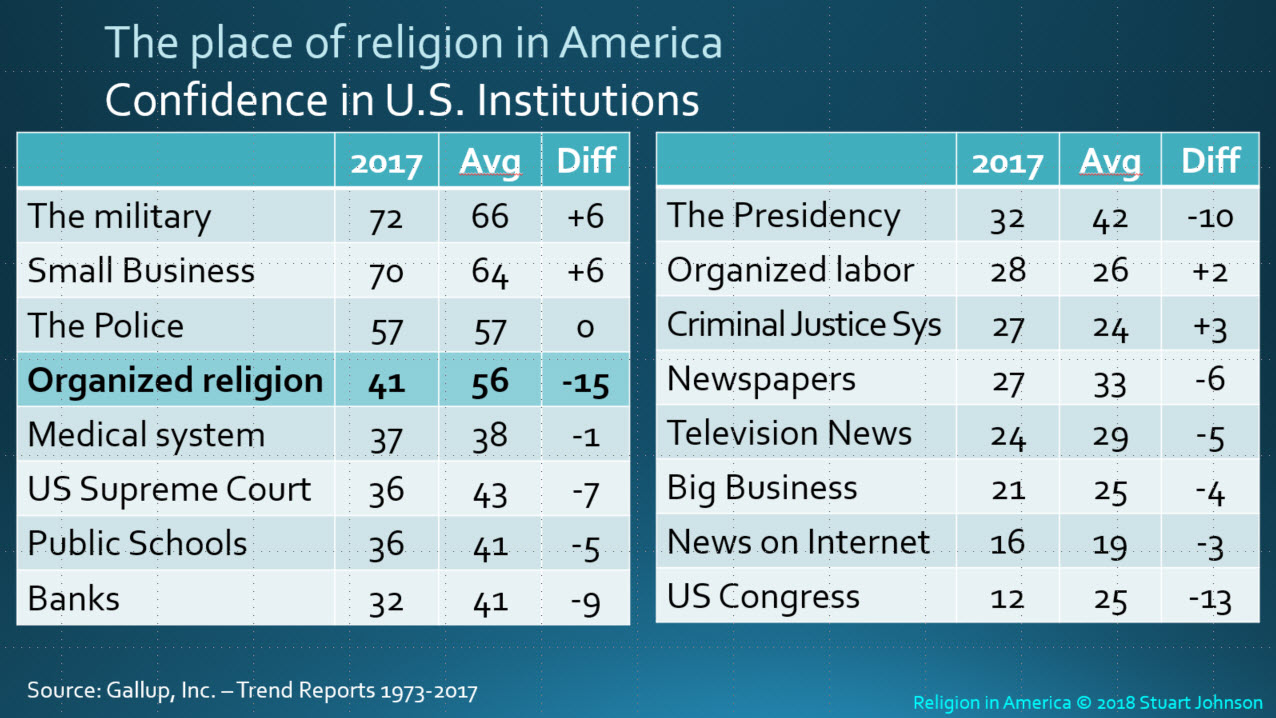

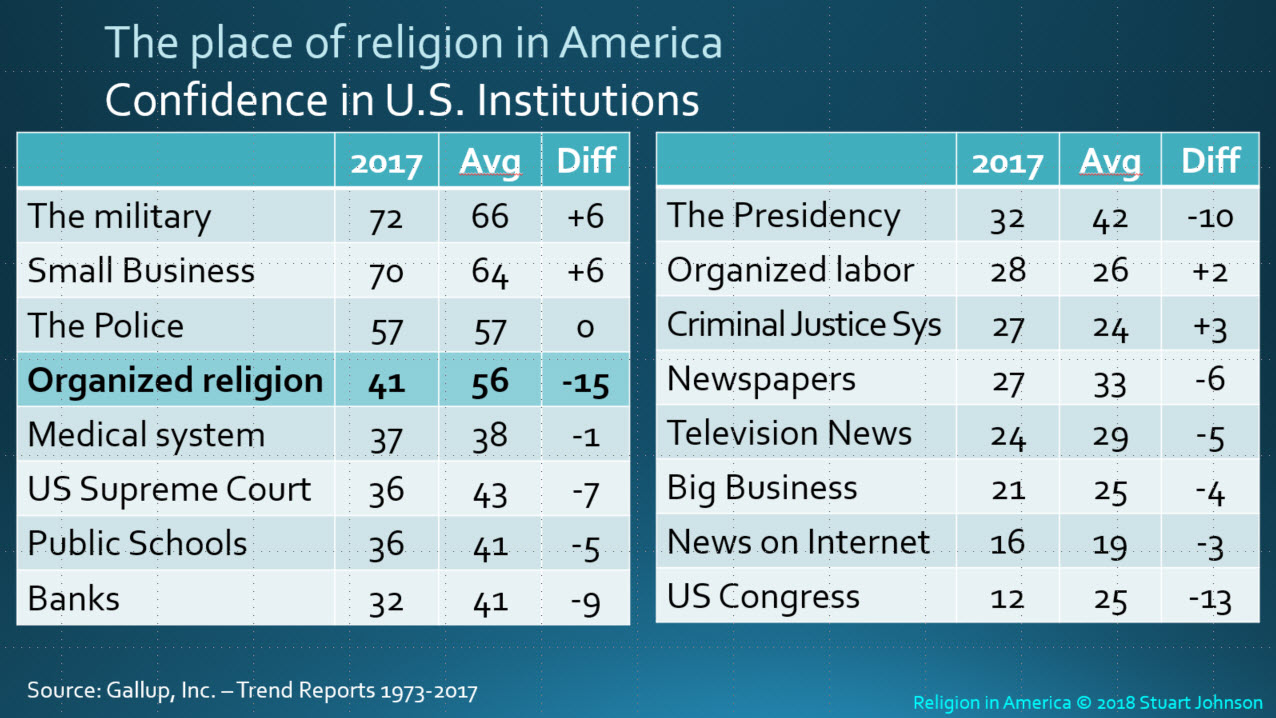

You can see from the chart above that only the military and small business had strong majority support in 2017 (combining those who responded a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence). Both were at a level slightly above their long-term average (the military since the survey began in 1973, small business on a continuous basis since 2007).

“The Police” is the only other institution with majority support, but much less than the first two. Given the media coverage of protests against police in several high profile situations in the past few years, it is remarkable that confidence has not wavered significantly over the 25 years it has been included—the score of 57% in 2017 matches the average over that time.

Organized religion first fell below majority confidence in 2002 and has stayed there since 2010. You can see from the list that half of the institutions measured are viewed with confidence by no more than one-third of those surveyed, including institutions that should be solid foundations of American society.

The continued downward arc of confidence levels led me to consider several specific examples, spurred by recent reading and one news report the other day:

The Second Amendment: Lost Trust?

The details of the debate over the necessary response to the recent school shooting in Parkland, Florida are beyond the scope of this article—and go well beyond gun control itself. Shortly before that tragedy occurred, I was browsing the New Books section of my local library and found Scalia Speaks, a collection of speeches by Antonin Scalia, late Supreme Court Justice, edited by his son, Christopher, and Edward Whelan, who clerked for Justice Scalia. (While on opposite ends of the judicial spectrum, the foreword to the book was written by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who developed a close friendship with Scalia while both served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in the 1980s. Both would meet again as justices on the U.S. Supreme Court.)

In a 2007 speech to Le Cercle, Justice Scalia addressed differences between American and European values. (Le Cercle is a group of European and American parliamentarians, diplomats, intelligence officials, bankers, and business leaders founded in the 1950s by West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer and French prime minister Antoine Pinay). In part of the speech, he walked through the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution—as an example of the differences in viewpoint and values.

While my point here is to talk about the Second Amendment and trust, it could be helpful to listen to Justice Scalia’s discussion of the First Amendment to get a sense of perspective (especially given the sensitivity today on many university campuses to protect students from speech that makes them uncomfortable, as well as the subject of Cybercrime in the second paragraph, both of which I will touch on later):

The First Amendment, often considered by Americans to be the proverbial jewel in the crown that is the U.S. Constitution, staunchly defends freedom of speech. Americans have proven themselves to be willing to protect that freedom against all manner of detractors; willing to display the thick skin that the First Amendment requires, and to recognize that the right to speak is far more important than a right not to be offended by what is spoken. Thus, when the Nazi Party of America planned to march through the streets of Skokie, Illinois, in 1977, its right to do so was supported by the American Civil Liberties Union and protected by the courts despite the repugnancy of its message.

To be sure, Europeans also value the freedom of speech and its importance to a functioning democracy. But they are far more willing to suppress a speaker’s message when it might prove inflammatory to the populace at large, or even when it might be thought to erode national culture. Thus, laws such as those banning pro-Nazi propaganda that would never pass constitutional muster in the United State are not atypical in Europe. In November 2002, the Council of Europe approved an “Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime” that would make it illegal to distribute anything online which “advocates, promotes or incites hatred [or] discrimination.” A spokesman for the United States Department of Justice said (quite correctly) that his county could not be part to such a treaty because of the First Amendment.

It is easy, isn’t it, to think that repugnant speech should not be allowed, yet our constitution in the U.S. has classified only a narrow range of expression as not protected or limited: pornography, incitement (i.e., falsely shouting fire in a crowded theater), libel, etc. Speech that merely offends is protected, though tell that to speakers who have not been welcome or disinvited from campuses across the country. Because of this, Scalia used as an example in another speech his decision that joined the majority in affirming that flag burning qualified as protected speech (expression) under the Constitution, even though he personally viewed the practice as deplorable.

On the Second Amendment, Justice Scalia went on:

The Second Amendment, which protects the right to bear arms, is another source of vast cultural differences between Americans and Europeans. Our Founders, having witnessed firsthand the indignities and abuses that overeager governments can impose on their own citizens, believed in a citizen’s rights to bear arms for protection against, among other things, the state itself. In number 46 of the Federalist Papers, James Madison speaks contemptuously of the governments of Europe, which are “afraid to trust the people with arms.” Even today, whether for hobby, hunting, or self-defense, Americans believe strongly in the right to own a gun. There are nearly two hundred million guns in private American hands, or roughly one per person, dispersed among one-third to one-half o American households. By contrast, Europeans have largely abandoned their guns, preferring to trust the state with a monopoly on weaponry.

It was important to include that whole paragraph here, not just the first half, so you can see he full context. What echoed in my mind after the Florida school shooting, however, was the quote from James Madison, suggesting that the governments of Europe were “afraid to trust the people with arms.” Where are we today? For us, it is not (supposed to be) the opinions of an elite that guides us, so we have to ask, have we reached the point where the people are afraid to trust each other with the right to bear arms?

Will it ever be possible to find the kind of safety many of us felt when attending school decades ago, (in my case, the far south side of Chicago)? Is it as simple as restricting access to automatic weapons and other firearms created for maximum lethal power, and keeping firearms out of the hands of the mentally ill? Frankly, gun advocates and the NRA might gain some trust were they to join the larger American culture in suggesting such restrictions. While this may seem like giving up an absolute right, there are parallels with the First Amendment, where civility and some sense of common cause or at least minimal respect, could help reduce violence over opposing or repugnant views.

In addition, however, there remain other societal factors—violence in entertainment; the slow breakdown in family structure and values along with the loss of a strong middle class that has heightened the divide between rich and poor (see Charles Murray’s Coming Apart); how we approach mental illness; and the general question of declining trust in societal institutions—in a very real sense, trust in ourselves.

Is that real?

A recent segment on “Chicago Tonight,” a news program aired on my local PBS station, WTTW in Chicago, featured a segment on artificial intelligence (AI). A professor from the University of Chicago explained an application of AI that was of particular interest because of discussions about the final design of the Obama Presidential Library to be built in an area near the U. of C. campus.

The segment dealt with the melding of audio and video recordings of then-President Obama. Somewhat like animatronic figures developed for Disney many years ago, the result of this effort was to present videos of Obama speaking, except the words coming out of his mouth were not those recorded when the video was made. Unlike the old Clutch Cargo cartoons that featured an obvious animated mouth on a rather lifeless face, the result of this effort was totally believable.

Asked about the application of such technology, the professor suggested it could be used to give voice to those with speech impairments. One problem, as the reporter astutely pointed out, is the issue of trust—how to handle “bad actors” in the application of AI. The professor admitted the need for security and proper guidelines but in so doing did not have a strong response to assure that such technology could not be hacked or used in an unethical or illegal manner.

Who do you trust? Consider two examples:

You may have received email from a friend apparently in trouble in a foreign country who requests emergency cash. These are usually easy to spot as fraudulent for obvious reasons (questionable location, writing that is clearly not the person represented, spelling and grammatical errors, etc.). But, what happens when someone you know very well calls with a similar plea. The voice sounds real, the dialogue (guided by AI) makes sense. Without use of some kind of secret code that some siblings or close friends develop to test the trust of such conversations, unknown to the AI agent, it might be impossible to suspect such a conversation as fraudulent.

In the case of the Obama video examples, it would not be a stretch to suggest that AI technology could take any text and make it come out of the mouth of any well-known person through videos and audio recordings—the ultimate virtual reality! But at what a cost to trust? What is to protect any person (much less the most famous) or the public from such deception? Such questions of trust go beyond this simple example, as you will see in the next section.

The Darkening Web

In addition to the material from Antonin Scalia’s speeches, my browsing of the New Books shelves at my local library also brought me in touch with “The Darkening Web: The War for Cyberspace” by Alexander Klimburg, who has had extensive experience as an advisor to governments and international organizations on cybersecurity strategy and Internet governance.

Klimburg addresses two aspects of the modern Internet and the networks that go beyond it to comprise the entire universe of cyberspace: technology and policy.

Internet Technology

Since the internet grew out of the need to connect several U.S. research universities and U.S. Department of Defense facilities, much of its early development stressed networking technology. Today it is represented by a whole alphabet soup of agencies and task forces around the world, most notably the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force). Taken together, the technical management of cyberspace is largely a function of civil society—private industry, universities, technology companies, and some government involvement (but not state control)—all aimed at making the technology of the Internet work effectively as a worldwide network of networks.

Allow me a brief explanation of the core technology. If this attempt to keep things simple is too much for you, feel free to skip ahead to the next section. If you wish to see even more detail, Kilmburg’s book has a comprehensive description, and there is a lot of good information readily available through Internet searches.

In its simplest terms, the Internet relies on a system of IP (Internet Protocol) addresses of physical places on the Internet (a 12-digit number in the form xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx) and a directory of domain names (Domain Name System), an easier-to-understand URL (Uniform Resource Locator) or alias (sjassociates.com). A DNS (Domain Name Server) looks up the URL and matching IP address, then routes the content using TCP (Transmission Control Protocol).

Thus, when you call up a page on this site, the request (URL) is routed to a Domain Name Server that matches sjassociates.com with its numerical IP address, on a server at our web host in Arizona. The content is then sent back and forth as needed between the two IP addresses (your computer and the web site). The content is broken into small packets, which can be sent in the most efficient manner, then assembled in the correct order when they arrive at your computer.

The naming and numbering system is key to the Internet. It is administered by ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) – “ICANN is a not-for-profit public-benefit corporation with participants from all over the world dedicated to keeping the Internet secure, stable and interoperable.”

TLDs (top level domains - .com, .org, .net) also include a list of top level country domains (ccTLDs), two-letter codes assigned to specific countries (.ca – Canada, .mx – Mexico) implemented by the IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority), under the auspices of ICANN. There are thirteen DNS root servers that maintain the master list of all the Internet’s authorized TLDs. One ccTLD I found interesting was .tv, which at first I thought was a new domain to specify sites associated with television. Wrong! It is actually assigned to the islands of Tuvalu, which sold the rights to their domain to a Canadian entrepreneur, and today nearly 50 percent of the tiny government’s revenue is derived from the sales of .tv domains. (Klimburg, p. 101)

Even at home today, it is likely that you have multiple devices sharing one router. Your router is identified by an IP number on the Internet, dynamically assigned by your service provider. The router itself keeps track of the individual devices on your own network and manages the flow of data to and from each device (using its own system of network addresses).

With more and more devices, from desktops to smartphones, smart TVs, streaming services, and smart appliances (thermostats, refrigerators, and a growing list of “things”) the number of devices within one location and the data they handle is sky rocketing. This puts a growing strain on your router (and any router extenders). The “IPv4” version of IP addresses used today has a capacity of just over 4-billion addresses. The new “IPv6” or “IPng” (IP next generation) has a far more sophisticated numbering system that will be able to handle a virtually unlimited number of connections—critical in the new “Internet of Things.”

This new capacity, however, has raised issues of privacy and trust. Currently, routers under IPv4 are normally assigned dynamic IP numbers by their service provider, making it hard in real time to identify who you are, especially when you are on a device connected through that router. One early proposal for IPv6 would have tied a device’s unique MAC address to an IP number. In the Internet of Things, anything with a MAC address could potentially identify you. Though the capability to do so has been removed from current IETF protocol, the suggestion remains in an RFC (Request for Comment), and Klimburg worries that it could be implemented at some point by bad actors—perhaps something like manufacturers of iPhones in China using the MAC address instead of the more widely adopted protocol, making it possible for the Chinese to assign the IPv6 number and track the phones.

Policy: Multi-stakeholder vs Cyber-Sovereignty.

Who controls the Internet, and how, is a much more value-laden argument than the huge task of making the technology work. While engineers have adhered to a “no kings, no presidents, no votes” approach to come up with the best solutions, that is not the case on the policy side, where the role of the state can become a major issue.

For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to the “web,” because of its common currency, though it is technically a subset of the entire interconnected cyberspace.

If everyone accessing the web did so with transparent and trustworthy intentions, policy would consume a relatively small footprint—more like rules of etiquette. However, we live in a world full of competing interests and bad actors (individual, tribal, national), which brings into play everything from mischievous hacking to fraud, espionage, and outright warfare. It is this “darkening web” that Klimburg is most concerned about—and his analysis is so deep in detail that I can only describe the tip of the iceberg here and encourage you to read the book for the whole story.

In the introduction to the book, Klimburg describes the struggle for control of cyberspace between what he calls the Free Internet coalition (also referred to as a multistakeholder model) and the Cyber-sovereignty faction.

The Free Internet coalition, or multistakeholder model, is a kind of free-trade arena, with most management tasks centered on providing access and managing the flow of information. Here, cybersecurity falls into defending against the bad guys who try to break in, and offensive, which can run the gamut from spying for defensive purposes to literal cyber warfare. Trust in the system can be broken when the bad guys are successful or, perhaps worse, when it turns out that the good guys on your side turn out to be bad actors, especially against their own citizens.

ICANN, referenced earlier in the technical description, espouses this view (see the ICANN website):

At the heart of ICANN's policy-making is what is called a "multistakeholder model". This is a community-based consensus-driven approach to policy-making. The idea is that Internet governance should mimic the structure of the Internet itself- borderless and open to all.

The Cyber-sovereign model is an authoritarian approach designed to control “bad content” and use the technology to weaponize information—represented chiefly by Russia, China, Syria and their partners. The roles of espionage, sabotage and warfare are played out not just against enemies of the state, but against their own people. Anyone reading Klimburg’s description of Russian activity around the world would wonder why Washington appears aghast at meddling in our elections—attempts to influence public opinion are nothing new and the Kremlin’s use of cyber-tactics in Crimea, Ukraine, and other places goes way beyond persuasion. Russia’s approach to the Internet has been hardened since Vladimir Putin returned to power in 2008 and turned up intelligence-driven policies in 2012 (flowing naturally from Putin’s years in the KGB).

In China, Klimburg describes the Great Firewall, which began with tens of thousands of “patriot” volunteers whose purpose was to post “corrections” to comments critical of the Chinese Communist Party. Now, the People’s Liberation Army is a cyber force often at odds with the forces of openness and progress that have made strides since the death of Chairman Mao in 1976. This threat, according to Klimburg, is darkening the web in China and causing some foreign businesses and individuals to become concerned.

Both Free Internet and Cyber-sovereign models face security issues, from simple hacking or snooping, to fraud and the power of major players (Google, Facebook, etc.) to collect information about us and turn it back on us in the form of targeted marketing. Cyber-sovereign operators face the potential of bringing the darkest side of cyberspace—managing “bad content” by blocking and censorship, and weaponizing information to engage in cyber warfare. Governments and businesses in the Free Internet coalition have not proven to be immune from such operations, which can significantly lower trust. As Klimburg puts it in his Introduction:

This book is about how the dreams of states are shaping international cybersecurity—the rising term to describe efforts to develop an international security architecture around state behavior in cyberspace. Within this context, I have talked about “cyber power” as the ability of states to exert power through and via cyberspace.

There are two different approaches to state cyber power: viewing it as simply another tool of traditional state conflict and espionage, on the one hand, and viewing it as a full-blown enabler of information warfare with overtones of propaganda and information control, on the other. There is no doubt which side favors which issue. For nearly two decades, Russia, together with like-minded states such as China and Iran, has repeatedly brought forward international resolutions attempting to support what is today called “national cyber sovereignty.” The Cyber-sovereignty faction consistently tried to emphasize that information in all its forms is a weapon, most often employed by “terrorists” but really extending to any information (read: Internet control) that is uncomfortable to the ruling elite. Essentially, it is shorthand for enabling wide-reaching Internet censorship and other types of activity to ensure the regime stability of these authoritarian states.

To date, [classical] liberal democracies, led by the United States and bound together in what I call the Free Internet coalition, have been engaged in what amounts to a holding action on this issue. In fact, they have largely refused to engage in it at all, instead emphasizing discussions on the more traditional use of cyber capabilities for both war and covert action. Discussions have ranged on examining thresholds for war—the United States has clearly stated that a serious cyberattack would be interpreted as a casus belli—and the application of international humanitarian law in any kind of cyber conflict. . . . But there is a major difference between these talks and those aimed at reducing and controlling nuclear weapons: there is no commonly desired end state, no shared nightmare that the two sides equally fear. And this means that it is difficult to see that the Cyber-sovereignty advocates may, in fact, be making headway with their core wish: the framing of information as a weapon. Over time, this could exert irresistible pressure to change the present Web to something much darker, where information is managed rather than free flowing and where instead of more freedom we will enjoy comprehensibly less.

After going into considerable detail about the challenges to prevent misuse of the Web (not only by foreign states, but through government and business forces within free societies), Klimburg touches on the topic of Artificial Intelligence that I referred to in the previous section:

If you think that the dark web is a far-fetched or rather singular notion, you may be surprised to know that among those who spend their days thinking about the future of cyber conflict, this prediction is fairly conservative. Some of the greatest technophiles share visions of cyber doom that are much more sinister and free from direct human agency entirely. In 2015, a group of prominent individuals, including Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, and Stephen Hawking, signed a letter with hundreds of others to warn of one danger: the rise of artificial intelligence (AI). According to these leading lights, AI could produce virtual demigods or pure logic that would make their own decisions on human life and the universe and everything, and this may not be a good thing for mankind. The assembled great minds followed Hawking’s 2014 newspaper editorial in which he stated, quite plainly, that the potential rise of AI could be an existential threat on the level of nuclear weapons.

Are these renowned technophiles just modern-day versions of the flat-earthers of old, who feared falling over the edge? Technological innovations are often portrayed with fear and loathing—travelling over 35 miles an hour was dangerous to the human body; people were not intended to fly; radio was “Satan’s tool” and television even worse; the Internet is a great way to communicate, but threatens our privacy . . . .well, perhaps some predictions are not total fabrications out of ignorance! Is AI feared simply because of its newness, or does it represent, as Hawking suggests, an existential threat of unimaginable scale?

Klimburg, with his considerable involvement in international cybersecurity, provides two chapters of suggestions to prevent the overthrow of the Free Internet coalition by the Cyber-sovereignty states, details which are far too technical to engage in this article. After mentioning the various actors whose participation is needed to prevent the loss of the Internet to dark forces, he suggests:

. . . The glue that binds these actors together is trust.

Trust is a tangible resource in cyberspace. It is hard coded into its most basic protocol development and has therefore clearly played a role in the extremely successful growth of the global Internet to date. It may even be the most decisive factor in the Internet itself. The power of individual actors on the Internet, not only states, but also single corporations and even individual people, is so extensive that there is a basic need to trust in each other’s good intentions. . . .

Trust-based networks are sometimes dismissed by government officials who think that the civilian version of trust is limited to looking someone deep in the eye and giving a firm handshake. But it goes much deeper than that. The norms among InfoSec professionals have given birth to extremely complicated and balanced processes for handling data and engaging in sensitive tasks, like renewing the keys of the Internet. [An elaborate process, described earlier in the book, done several times a year to ensure the integrity of the root servers for the Domain Name System.] . . .

But trust has long been an intangible feature of cyberspace as well. Prior to the Snowden revelations of American intelligence gathering, civil society and the cyber industry felt an implicit amount of trust in the workings of their liberal democratic governments. It was commonly accepted that as bad as the Russians, the Chinese, and others might have been in the casual violation of confidentiality or the conduct of true cyberattacks, the democratic governments of the United States and Europe would not play by these rules, would show a higher level of restraint. . . .

. . . Following the disclosures by Snowden and many other unexplained leaks, the trust in government of the InfoSec community, both civil society and business, was undeniably weakened.

Klimburg goes on to explore some very dark possibilities, including a “cybergeddon” of “country-crashing cyber conflict. .

. . As unlikely as it may seem, such a real cyber war is certainly no less probable than a nuclear exchange was during the Cold War, and my guess is that the threat is may orders of magnitude larger.” He then concludes:

The only way that we will get trust back into the wider issue of cybersecurity or data security is if these different communities at least try to understand each other’s wishes and fears. We don’t need to have the same dreams of cyberspace. But those of us who share the vision of the Internet as an agent for civilizational change need to understand what the sum of our fears is and what we can do about it.

Fake News and Declining Trust

Kilmburg’s book was completed before the 2016 presidential election in the United States, but he was able to write an Epilogue in December 2016, after the election, but before President Trump’s inauguration. A few relevant quotes:

The specific tools of Russian information warfare included the attempts at influencing public opinion through “strategic leakage” of hacked e-mails of the Democratic Party. This avenue of attack was able to take root only due to a simultaneous and I think even more pernicious weakening of the overall trust in the broader and mainstream media. Some of this weakening was clearly intentional—the deployment of paid-for trolls and support for Russian allies in the American (and European) far right. But at least some (or even most) of the purported “fake news” and similarly harmful memes that seemed to ricochet through social media, and which had been given significant weight by journalists and commentators, were most likely not directed by any foreign information warfare campaign . . . not produced by Russian spooks . . . [citing reliable sources] they were at least partially fabricated by a couple of dozen well-educated and hyper-fluent teenagers in Macedonia. These kids—often younger than eighteen—had been trying to make money feeling Facebook and other social media outlets for years, creating over 150 “news sites,” whose only job was to function as “click-bait” that easily attracted readers, even if only for some moments—moments that meant advertising income of many thousands of dollars a month when it went well. . . . . .

Kilmburg then goes on to suggest that while there will always be those who believe the black helicopters are ready to scoop them up, he was dismayed at the “the ability of tens of millions of the electorate to be so thoroughly confused and subtly discouraged by these often totally fake news items. . . . “ In other social media-addicted areas, such as northern Europe, he goes on, the populations seem more resilient and “their systems seems to have at least partially helped inoculate them, at least so far.” Personally, I have wondered for some time how the loss of civics education and now the increasing reliance on social media has impacted American voters. Have we not had enough good education in our republican form of government to inoculate us against half-truths and deception? This includes not just formal education, but journalism, entertainment, and the social institutions that were for so long the bedrock of American civil society.

Coming full circle

Klimburg puzzles over the data from the same Gallup poll on America’s falling confidence in its institutions that I used at the beginning of this blog.

It is hard to image that any political system can be left unchallenged when only 6 percent of an electorate thinks of its representatives in positive terms. Whatever the cause for this, it is clear that it is home-grown. No foreign cyber giant has somehow crossed the Atlantic (or the Pacific) and induced this weakness in trust in the US body politic, although foreign powers could well be enticed to exploit it. That exploitation wasn’t hard, for the level of trust in the wider media was equally shocking: only about 20 percent polled had confidence in newspaper and media news.

[Klimburg’s reference to 6-percent confidence in Congress refers to those responding with a “great deal” of confidence. My chart, showing 12-percent, includes also those who responded with “quite a lot” of confidence.]

All is not lost, however, as Klimburg concludes:

. . . The ability of civil society and news media in democratic societies everywhere to respond to the so-called “fake news phenomenon” leaves me hopeful that the technical vulnerabilities in the wider information ecosystem can be patched. Some of the topics are already being discussed, dealing for instance with algorithmic informational bubbles and the general workings of large social media organizations, and tempered with the need to preserve human rights and above all the freedom of speech. As a result, many thousands or even tens of thousands on new individuals directly and indirectly in the governance of this new domain of human behavior. Many more than that will have been warned by this seeming small detonation of info war, and will tacitly support the efforts of civil society, industry, and government actors that have taken up the fight on their behalf. They will reinforce the battle taking place for the future of cyberspace and the free web, which is nothing less than the struggle for the heart of modern democratic society. It will not be a struggle that passes quicky—but just as singular individuals in previous decades made a crucial difference, we can all do so today.

Can the downward slope of trust be reversed?

Social media, reality TV, and 24-hour news, I’m afraid, have turned much of America into one giant shouting match. We need to learn to talk—even to listen—and not just try to out-shout each other. Following the Parkland school shooting, we were once again urged to “see something, say something.” That may be good, but it works best in a community of real connections and high trust. There is significant danger that such a slogan can also lead to distrust, suspicion, judgmentalism and growing fear Combining my starting point of the diminishing confidence in institutions with the tragedies of a school shooting, the fears of technology run amok through artificial intelligence and a darkening Web, how can we restore trust? . . . in our communities? . . . in our neighbors (literal and virtual)? . . . in our institutions?

As historian David Kennedy and former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice recently urged on the PBS program “American Creed,” we are losing something precious when we let slip through our fingers the great Ideas of government by the people and “out of many, one” that still define the American experiment. Are we forever committed to a downward slope or can trust in each other and our institutions be restored?

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: March 65, 2018 Accessed 3,056 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: General / Topics: Censorship • Change • Demographics • Ethics • Government • Information • Information Management • Internet • Media • Opinion research • Policy • Science & Technology • Social Movements • Trends

Trust

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: March 65, 2018

Can we stop the downward slide?…

Back in May of 2015, I wrote on the issue of trust in an article, “Who Do You Trust?,” making reference to the TV game show by that name, which ran from 1958 to 1962. It was interesting to review that article myself, considering some issues that have appeared in the news since then. Given current circumstances and spurred by a couple of books I’ve been reading recently, it seemed to be a good time to return to the topic of trust.

America’s declining confidence in social institutions

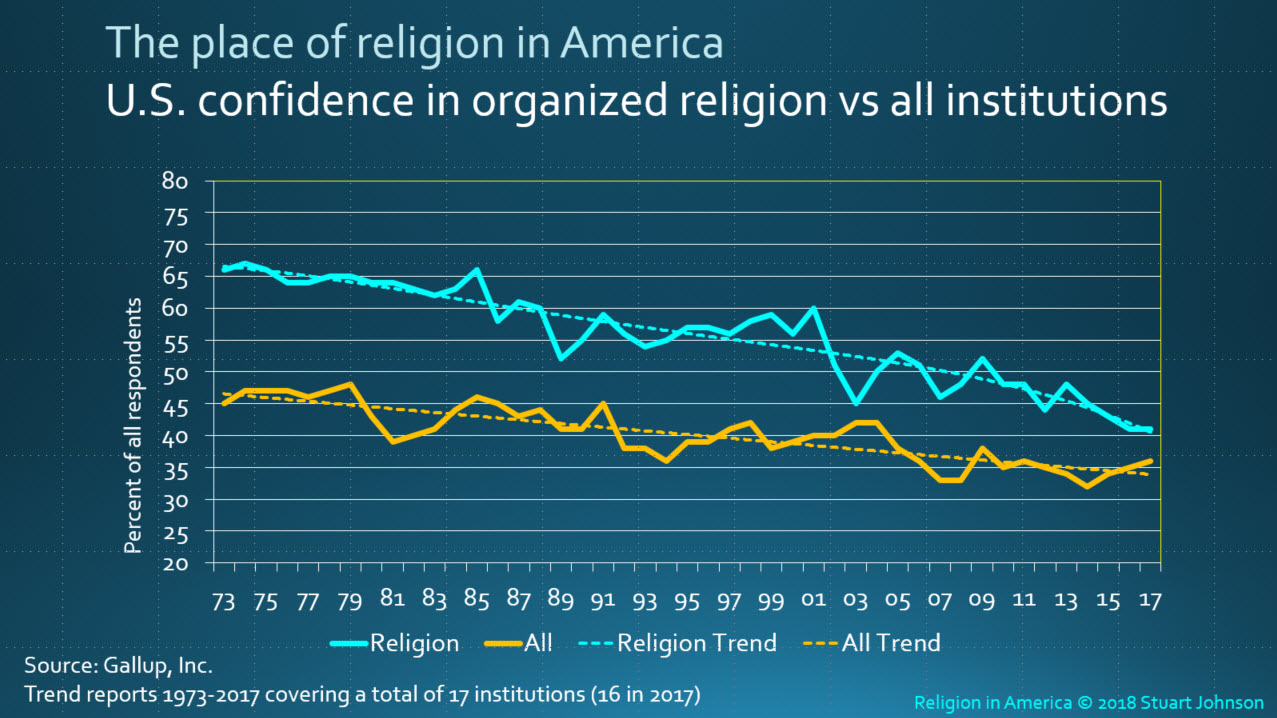

Research by the Gallup organization since 1973 shows a steady decline in the confidence of Americans in our major social institutions. For the purposes of this article, it seems fair to equate the term “trust” with “confidence,” the word Gallup uses in soliciting opinions. The chart below comes from my report on Religion in America, so it shows how organized religion compares to all institutions included in the survey (16 in 2017).

The data on this and the following chart represent selection of either a “Great deal” or “Quite a lot” of confidence,

representing the top two scores on a five-point rating scale, from “Great deal” to “None.”

While the drop in organized religion is significant, it is the general decline for all institutions over more than four decades that is central to my point here. (You can read more analysis on organized religion in my Religion in America report).

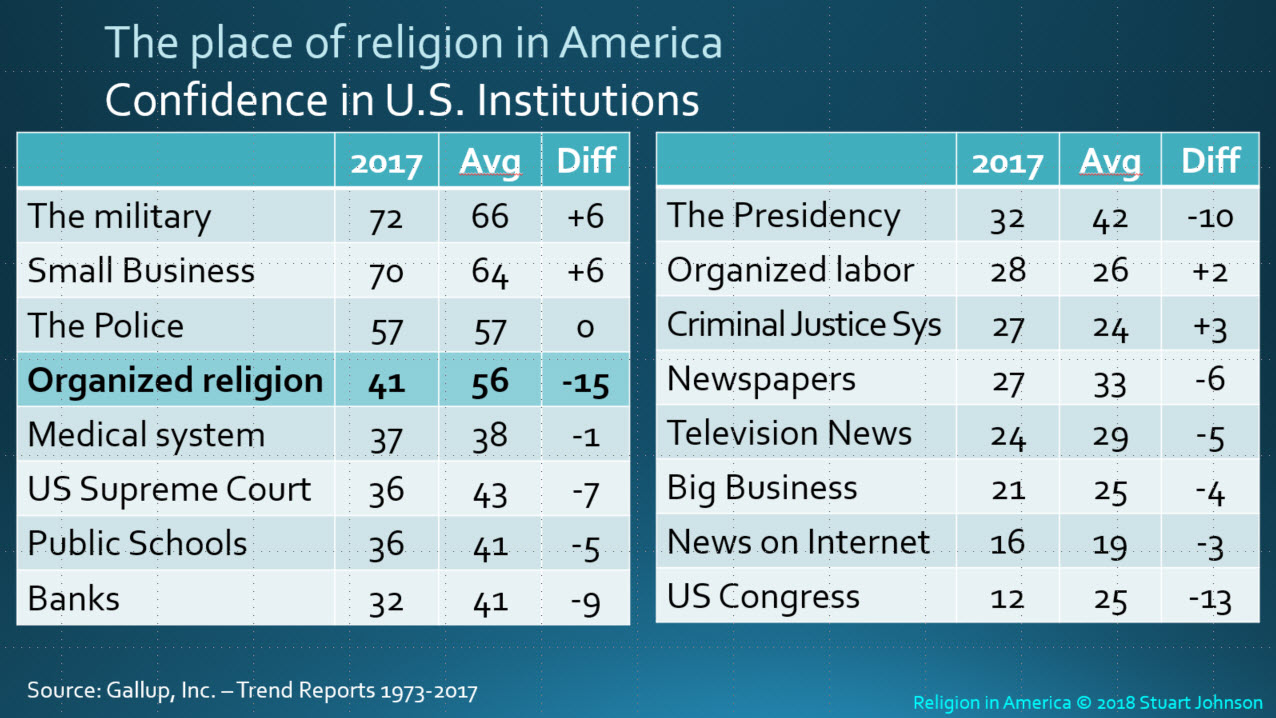

You can see from the chart above that only the military and small business had strong majority support in 2017 (combining those who responded a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence). Both were at a level slightly above their long-term average (the military since the survey began in 1973, small business on a continuous basis since 2007).

“The Police” is the only other institution with majority support, but much less than the first two. Given the media coverage of protests against police in several high profile situations in the past few years, it is remarkable that confidence has not wavered significantly over the 25 years it has been included—the score of 57% in 2017 matches the average over that time.

Organized religion first fell below majority confidence in 2002 and has stayed there since 2010. You can see from the list that half of the institutions measured are viewed with confidence by no more than one-third of those surveyed, including institutions that should be solid foundations of American society.

The continued downward arc of confidence levels led me to consider several specific examples, spurred by recent reading and one news report the other day:

The Second Amendment: Lost Trust?

The details of the debate over the necessary response to the recent school shooting in Parkland, Florida are beyond the scope of this article—and go well beyond gun control itself. Shortly before that tragedy occurred, I was browsing the New Books section of my local library and found Scalia Speaks, a collection of speeches by Antonin Scalia, late Supreme Court Justice, edited by his son, Christopher, and Edward Whelan, who clerked for Justice Scalia. (While on opposite ends of the judicial spectrum, the foreword to the book was written by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who developed a close friendship with Scalia while both served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in the 1980s. Both would meet again as justices on the U.S. Supreme Court.)

In a 2007 speech to Le Cercle, Justice Scalia addressed differences between American and European values. (Le Cercle is a group of European and American parliamentarians, diplomats, intelligence officials, bankers, and business leaders founded in the 1950s by West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer and French prime minister Antoine Pinay). In part of the speech, he walked through the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution—as an example of the differences in viewpoint and values.

While my point here is to talk about the Second Amendment and trust, it could be helpful to listen to Justice Scalia’s discussion of the First Amendment to get a sense of perspective (especially given the sensitivity today on many university campuses to protect students from speech that makes them uncomfortable, as well as the subject of Cybercrime in the second paragraph, both of which I will touch on later):

The First Amendment, often considered by Americans to be the proverbial jewel in the crown that is the U.S. Constitution, staunchly defends freedom of speech. Americans have proven themselves to be willing to protect that freedom against all manner of detractors; willing to display the thick skin that the First Amendment requires, and to recognize that the right to speak is far more important than a right not to be offended by what is spoken. Thus, when the Nazi Party of America planned to march through the streets of Skokie, Illinois, in 1977, its right to do so was supported by the American Civil Liberties Union and protected by the courts despite the repugnancy of its message.

To be sure, Europeans also value the freedom of speech and its importance to a functioning democracy. But they are far more willing to suppress a speaker’s message when it might prove inflammatory to the populace at large, or even when it might be thought to erode national culture. Thus, laws such as those banning pro-Nazi propaganda that would never pass constitutional muster in the United State are not atypical in Europe. In November 2002, the Council of Europe approved an “Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime” that would make it illegal to distribute anything online which “advocates, promotes or incites hatred [or] discrimination.” A spokesman for the United States Department of Justice said (quite correctly) that his county could not be part to such a treaty because of the First Amendment.

It is easy, isn’t it, to think that repugnant speech should not be allowed, yet our constitution in the U.S. has classified only a narrow range of expression as not protected or limited: pornography, incitement (i.e., falsely shouting fire in a crowded theater), libel, etc. Speech that merely offends is protected, though tell that to speakers who have not been welcome or disinvited from campuses across the country. Because of this, Scalia used as an example in another speech his decision that joined the majority in affirming that flag burning qualified as protected speech (expression) under the Constitution, even though he personally viewed the practice as deplorable.

On the Second Amendment, Justice Scalia went on:

The Second Amendment, which protects the right to bear arms, is another source of vast cultural differences between Americans and Europeans. Our Founders, having witnessed firsthand the indignities and abuses that overeager governments can impose on their own citizens, believed in a citizen’s rights to bear arms for protection against, among other things, the state itself. In number 46 of the Federalist Papers, James Madison speaks contemptuously of the governments of Europe, which are “afraid to trust the people with arms.” Even today, whether for hobby, hunting, or self-defense, Americans believe strongly in the right to own a gun. There are nearly two hundred million guns in private American hands, or roughly one per person, dispersed among one-third to one-half o American households. By contrast, Europeans have largely abandoned their guns, preferring to trust the state with a monopoly on weaponry.

It was important to include that whole paragraph here, not just the first half, so you can see he full context. What echoed in my mind after the Florida school shooting, however, was the quote from James Madison, suggesting that the governments of Europe were “afraid to trust the people with arms.” Where are we today? For us, it is not (supposed to be) the opinions of an elite that guides us, so we have to ask, have we reached the point where the people are afraid to trust each other with the right to bear arms?

Will it ever be possible to find the kind of safety many of us felt when attending school decades ago, (in my case, the far south side of Chicago)? Is it as simple as restricting access to automatic weapons and other firearms created for maximum lethal power, and keeping firearms out of the hands of the mentally ill? Frankly, gun advocates and the NRA might gain some trust were they to join the larger American culture in suggesting such restrictions. While this may seem like giving up an absolute right, there are parallels with the First Amendment, where civility and some sense of common cause or at least minimal respect, could help reduce violence over opposing or repugnant views.

In addition, however, there remain other societal factors—violence in entertainment; the slow breakdown in family structure and values along with the loss of a strong middle class that has heightened the divide between rich and poor (see Charles Murray’s Coming Apart); how we approach mental illness; and the general question of declining trust in societal institutions—in a very real sense, trust in ourselves.

Is that real?

A recent segment on “Chicago Tonight,” a news program aired on my local PBS station, WTTW in Chicago, featured a segment on artificial intelligence (AI). A professor from the University of Chicago explained an application of AI that was of particular interest because of discussions about the final design of the Obama Presidential Library to be built in an area near the U. of C. campus.

The segment dealt with the melding of audio and video recordings of then-President Obama. Somewhat like animatronic figures developed for Disney many years ago, the result of this effort was to present videos of Obama speaking, except the words coming out of his mouth were not those recorded when the video was made. Unlike the old Clutch Cargo cartoons that featured an obvious animated mouth on a rather lifeless face, the result of this effort was totally believable.

Asked about the application of such technology, the professor suggested it could be used to give voice to those with speech impairments. One problem, as the reporter astutely pointed out, is the issue of trust—how to handle “bad actors” in the application of AI. The professor admitted the need for security and proper guidelines but in so doing did not have a strong response to assure that such technology could not be hacked or used in an unethical or illegal manner.

Who do you trust? Consider two examples:

You may have received email from a friend apparently in trouble in a foreign country who requests emergency cash. These are usually easy to spot as fraudulent for obvious reasons (questionable location, writing that is clearly not the person represented, spelling and grammatical errors, etc.). But, what happens when someone you know very well calls with a similar plea. The voice sounds real, the dialogue (guided by AI) makes sense. Without use of some kind of secret code that some siblings or close friends develop to test the trust of such conversations, unknown to the AI agent, it might be impossible to suspect such a conversation as fraudulent.

In the case of the Obama video examples, it would not be a stretch to suggest that AI technology could take any text and make it come out of the mouth of any well-known person through videos and audio recordings—the ultimate virtual reality! But at what a cost to trust? What is to protect any person (much less the most famous) or the public from such deception? Such questions of trust go beyond this simple example, as you will see in the next section.

The Darkening Web

In addition to the material from Antonin Scalia’s speeches, my browsing of the New Books shelves at my local library also brought me in touch with “The Darkening Web: The War for Cyberspace” by Alexander Klimburg, who has had extensive experience as an advisor to governments and international organizations on cybersecurity strategy and Internet governance.

Klimburg addresses two aspects of the modern Internet and the networks that go beyond it to comprise the entire universe of cyberspace: technology and policy.

Internet Technology

Since the internet grew out of the need to connect several U.S. research universities and U.S. Department of Defense facilities, much of its early development stressed networking technology. Today it is represented by a whole alphabet soup of agencies and task forces around the world, most notably the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force). Taken together, the technical management of cyberspace is largely a function of civil society—private industry, universities, technology companies, and some government involvement (but not state control)—all aimed at making the technology of the Internet work effectively as a worldwide network of networks.

Allow me a brief explanation of the core technology. If this attempt to keep things simple is too much for you, feel free to skip ahead to the next section. If you wish to see even more detail, Kilmburg’s book has a comprehensive description, and there is a lot of good information readily available through Internet searches.

In its simplest terms, the Internet relies on a system of IP (Internet Protocol) addresses of physical places on the Internet (a 12-digit number in the form xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx) and a directory of domain names (Domain Name System), an easier-to-understand URL (Uniform Resource Locator) or alias (sjassociates.com). A DNS (Domain Name Server) looks up the URL and matching IP address, then routes the content using TCP (Transmission Control Protocol).

Thus, when you call up a page on this site, the request (URL) is routed to a Domain Name Server that matches sjassociates.com with its numerical IP address, on a server at our web host in Arizona. The content is then sent back and forth as needed between the two IP addresses (your computer and the web site). The content is broken into small packets, which can be sent in the most efficient manner, then assembled in the correct order when they arrive at your computer.

The naming and numbering system is key to the Internet. It is administered by ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) – “ICANN is a not-for-profit public-benefit corporation with participants from all over the world dedicated to keeping the Internet secure, stable and interoperable.”

TLDs (top level domains - .com, .org, .net) also include a list of top level country domains (ccTLDs), two-letter codes assigned to specific countries (.ca – Canada, .mx – Mexico) implemented by the IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority), under the auspices of ICANN. There are thirteen DNS root servers that maintain the master list of all the Internet’s authorized TLDs. One ccTLD I found interesting was .tv, which at first I thought was a new domain to specify sites associated with television. Wrong! It is actually assigned to the islands of Tuvalu, which sold the rights to their domain to a Canadian entrepreneur, and today nearly 50 percent of the tiny government’s revenue is derived from the sales of .tv domains. (Klimburg, p. 101)

Even at home today, it is likely that you have multiple devices sharing one router. Your router is identified by an IP number on the Internet, dynamically assigned by your service provider. The router itself keeps track of the individual devices on your own network and manages the flow of data to and from each device (using its own system of network addresses).

With more and more devices, from desktops to smartphones, smart TVs, streaming services, and smart appliances (thermostats, refrigerators, and a growing list of “things”) the number of devices within one location and the data they handle is sky rocketing. This puts a growing strain on your router (and any router extenders). The “IPv4” version of IP addresses used today has a capacity of just over 4-billion addresses. The new “IPv6” or “IPng” (IP next generation) has a far more sophisticated numbering system that will be able to handle a virtually unlimited number of connections—critical in the new “Internet of Things.”

This new capacity, however, has raised issues of privacy and trust. Currently, routers under IPv4 are normally assigned dynamic IP numbers by their service provider, making it hard in real time to identify who you are, especially when you are on a device connected through that router. One early proposal for IPv6 would have tied a device’s unique MAC address to an IP number. In the Internet of Things, anything with a MAC address could potentially identify you. Though the capability to do so has been removed from current IETF protocol, the suggestion remains in an RFC (Request for Comment), and Klimburg worries that it could be implemented at some point by bad actors—perhaps something like manufacturers of iPhones in China using the MAC address instead of the more widely adopted protocol, making it possible for the Chinese to assign the IPv6 number and track the phones.

Policy: Multi-stakeholder vs Cyber-Sovereignty.

Who controls the Internet, and how, is a much more value-laden argument than the huge task of making the technology work. While engineers have adhered to a “no kings, no presidents, no votes” approach to come up with the best solutions, that is not the case on the policy side, where the role of the state can become a major issue.

For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to the “web,” because of its common currency, though it is technically a subset of the entire interconnected cyberspace.

If everyone accessing the web did so with transparent and trustworthy intentions, policy would consume a relatively small footprint—more like rules of etiquette. However, we live in a world full of competing interests and bad actors (individual, tribal, national), which brings into play everything from mischievous hacking to fraud, espionage, and outright warfare. It is this “darkening web” that Klimburg is most concerned about—and his analysis is so deep in detail that I can only describe the tip of the iceberg here and encourage you to read the book for the whole story.

In the introduction to the book, Klimburg describes the struggle for control of cyberspace between what he calls the Free Internet coalition (also referred to as a multistakeholder model) and the Cyber-sovereignty faction.

The Free Internet coalition, or multistakeholder model, is a kind of free-trade arena, with most management tasks centered on providing access and managing the flow of information. Here, cybersecurity falls into defending against the bad guys who try to break in, and offensive, which can run the gamut from spying for defensive purposes to literal cyber warfare. Trust in the system can be broken when the bad guys are successful or, perhaps worse, when it turns out that the good guys on your side turn out to be bad actors, especially against their own citizens.

ICANN, referenced earlier in the technical description, espouses this view (see the ICANN website):

At the heart of ICANN's policy-making is what is called a "multistakeholder model". This is a community-based consensus-driven approach to policy-making. The idea is that Internet governance should mimic the structure of the Internet itself- borderless and open to all.

The Cyber-sovereign model is an authoritarian approach designed to control “bad content” and use the technology to weaponize information—represented chiefly by Russia, China, Syria and their partners. The roles of espionage, sabotage and warfare are played out not just against enemies of the state, but against their own people. Anyone reading Klimburg’s description of Russian activity around the world would wonder why Washington appears aghast at meddling in our elections—attempts to influence public opinion are nothing new and the Kremlin’s use of cyber-tactics in Crimea, Ukraine, and other places goes way beyond persuasion. Russia’s approach to the Internet has been hardened since Vladimir Putin returned to power in 2008 and turned up intelligence-driven policies in 2012 (flowing naturally from Putin’s years in the KGB).

In China, Klimburg describes the Great Firewall, which began with tens of thousands of “patriot” volunteers whose purpose was to post “corrections” to comments critical of the Chinese Communist Party. Now, the People’s Liberation Army is a cyber force often at odds with the forces of openness and progress that have made strides since the death of Chairman Mao in 1976. This threat, according to Klimburg, is darkening the web in China and causing some foreign businesses and individuals to become concerned.

Both Free Internet and Cyber-sovereign models face security issues, from simple hacking or snooping, to fraud and the power of major players (Google, Facebook, etc.) to collect information about us and turn it back on us in the form of targeted marketing. Cyber-sovereign operators face the potential of bringing the darkest side of cyberspace—managing “bad content” by blocking and censorship, and weaponizing information to engage in cyber warfare. Governments and businesses in the Free Internet coalition have not proven to be immune from such operations, which can significantly lower trust. As Klimburg puts it in his Introduction:

This book is about how the dreams of states are shaping international cybersecurity—the rising term to describe efforts to develop an international security architecture around state behavior in cyberspace. Within this context, I have talked about “cyber power” as the ability of states to exert power through and via cyberspace.

There are two different approaches to state cyber power: viewing it as simply another tool of traditional state conflict and espionage, on the one hand, and viewing it as a full-blown enabler of information warfare with overtones of propaganda and information control, on the other. There is no doubt which side favors which issue. For nearly two decades, Russia, together with like-minded states such as China and Iran, has repeatedly brought forward international resolutions attempting to support what is today called “national cyber sovereignty.” The Cyber-sovereignty faction consistently tried to emphasize that information in all its forms is a weapon, most often employed by “terrorists” but really extending to any information (read: Internet control) that is uncomfortable to the ruling elite. Essentially, it is shorthand for enabling wide-reaching Internet censorship and other types of activity to ensure the regime stability of these authoritarian states.

To date, [classical] liberal democracies, led by the United States and bound together in what I call the Free Internet coalition, have been engaged in what amounts to a holding action on this issue. In fact, they have largely refused to engage in it at all, instead emphasizing discussions on the more traditional use of cyber capabilities for both war and covert action. Discussions have ranged on examining thresholds for war—the United States has clearly stated that a serious cyberattack would be interpreted as a casus belli—and the application of international humanitarian law in any kind of cyber conflict. . . . But there is a major difference between these talks and those aimed at reducing and controlling nuclear weapons: there is no commonly desired end state, no shared nightmare that the two sides equally fear. And this means that it is difficult to see that the Cyber-sovereignty advocates may, in fact, be making headway with their core wish: the framing of information as a weapon. Over time, this could exert irresistible pressure to change the present Web to something much darker, where information is managed rather than free flowing and where instead of more freedom we will enjoy comprehensibly less.

After going into considerable detail about the challenges to prevent misuse of the Web (not only by foreign states, but through government and business forces within free societies), Klimburg touches on the topic of Artificial Intelligence that I referred to in the previous section:

If you think that the dark web is a far-fetched or rather singular notion, you may be surprised to know that among those who spend their days thinking about the future of cyber conflict, this prediction is fairly conservative. Some of the greatest technophiles share visions of cyber doom that are much more sinister and free from direct human agency entirely. In 2015, a group of prominent individuals, including Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, and Stephen Hawking, signed a letter with hundreds of others to warn of one danger: the rise of artificial intelligence (AI). According to these leading lights, AI could produce virtual demigods or pure logic that would make their own decisions on human life and the universe and everything, and this may not be a good thing for mankind. The assembled great minds followed Hawking’s 2014 newspaper editorial in which he stated, quite plainly, that the potential rise of AI could be an existential threat on the level of nuclear weapons.

Are these renowned technophiles just modern-day versions of the flat-earthers of old, who feared falling over the edge? Technological innovations are often portrayed with fear and loathing—travelling over 35 miles an hour was dangerous to the human body; people were not intended to fly; radio was “Satan’s tool” and television even worse; the Internet is a great way to communicate, but threatens our privacy . . . .well, perhaps some predictions are not total fabrications out of ignorance! Is AI feared simply because of its newness, or does it represent, as Hawking suggests, an existential threat of unimaginable scale?

Klimburg, with his considerable involvement in international cybersecurity, provides two chapters of suggestions to prevent the overthrow of the Free Internet coalition by the Cyber-sovereignty states, details which are far too technical to engage in this article. After mentioning the various actors whose participation is needed to prevent the loss of the Internet to dark forces, he suggests:

. . . The glue that binds these actors together is trust.

Trust is a tangible resource in cyberspace. It is hard coded into its most basic protocol development and has therefore clearly played a role in the extremely successful growth of the global Internet to date. It may even be the most decisive factor in the Internet itself. The power of individual actors on the Internet, not only states, but also single corporations and even individual people, is so extensive that there is a basic need to trust in each other’s good intentions. . . .

Trust-based networks are sometimes dismissed by government officials who think that the civilian version of trust is limited to looking someone deep in the eye and giving a firm handshake. But it goes much deeper than that. The norms among InfoSec professionals have given birth to extremely complicated and balanced processes for handling data and engaging in sensitive tasks, like renewing the keys of the Internet. [An elaborate process, described earlier in the book, done several times a year to ensure the integrity of the root servers for the Domain Name System.] . . .

But trust has long been an intangible feature of cyberspace as well. Prior to the Snowden revelations of American intelligence gathering, civil society and the cyber industry felt an implicit amount of trust in the workings of their liberal democratic governments. It was commonly accepted that as bad as the Russians, the Chinese, and others might have been in the casual violation of confidentiality or the conduct of true cyberattacks, the democratic governments of the United States and Europe would not play by these rules, would show a higher level of restraint. . . .

. . . Following the disclosures by Snowden and many other unexplained leaks, the trust in government of the InfoSec community, both civil society and business, was undeniably weakened.

Klimburg goes on to explore some very dark possibilities, including a “cybergeddon” of “country-crashing cyber conflict. .

. . As unlikely as it may seem, such a real cyber war is certainly no less probable than a nuclear exchange was during the Cold War, and my guess is that the threat is may orders of magnitude larger.” He then concludes:

The only way that we will get trust back into the wider issue of cybersecurity or data security is if these different communities at least try to understand each other’s wishes and fears. We don’t need to have the same dreams of cyberspace. But those of us who share the vision of the Internet as an agent for civilizational change need to understand what the sum of our fears is and what we can do about it.

Fake News and Declining Trust

Kilmburg’s book was completed before the 2016 presidential election in the United States, but he was able to write an Epilogue in December 2016, after the election, but before President Trump’s inauguration. A few relevant quotes:

The specific tools of Russian information warfare included the attempts at influencing public opinion through “strategic leakage” of hacked e-mails of the Democratic Party. This avenue of attack was able to take root only due to a simultaneous and I think even more pernicious weakening of the overall trust in the broader and mainstream media. Some of this weakening was clearly intentional—the deployment of paid-for trolls and support for Russian allies in the American (and European) far right. But at least some (or even most) of the purported “fake news” and similarly harmful memes that seemed to ricochet through social media, and which had been given significant weight by journalists and commentators, were most likely not directed by any foreign information warfare campaign . . . not produced by Russian spooks . . . [citing reliable sources] they were at least partially fabricated by a couple of dozen well-educated and hyper-fluent teenagers in Macedonia. These kids—often younger than eighteen—had been trying to make money feeling Facebook and other social media outlets for years, creating over 150 “news sites,” whose only job was to function as “click-bait” that easily attracted readers, even if only for some moments—moments that meant advertising income of many thousands of dollars a month when it went well. . . . . .

Kilmburg then goes on to suggest that while there will always be those who believe the black helicopters are ready to scoop them up, he was dismayed at the “the ability of tens of millions of the electorate to be so thoroughly confused and subtly discouraged by these often totally fake news items. . . . “ In other social media-addicted areas, such as northern Europe, he goes on, the populations seem more resilient and “their systems seems to have at least partially helped inoculate them, at least so far.” Personally, I have wondered for some time how the loss of civics education and now the increasing reliance on social media has impacted American voters. Have we not had enough good education in our republican form of government to inoculate us against half-truths and deception? This includes not just formal education, but journalism, entertainment, and the social institutions that were for so long the bedrock of American civil society.

Coming full circle

Klimburg puzzles over the data from the same Gallup poll on America’s falling confidence in its institutions that I used at the beginning of this blog.

It is hard to image that any political system can be left unchallenged when only 6 percent of an electorate thinks of its representatives in positive terms. Whatever the cause for this, it is clear that it is home-grown. No foreign cyber giant has somehow crossed the Atlantic (or the Pacific) and induced this weakness in trust in the US body politic, although foreign powers could well be enticed to exploit it. That exploitation wasn’t hard, for the level of trust in the wider media was equally shocking: only about 20 percent polled had confidence in newspaper and media news.

[Klimburg’s reference to 6-percent confidence in Congress refers to those responding with a “great deal” of confidence. My chart, showing 12-percent, includes also those who responded with “quite a lot” of confidence.]

All is not lost, however, as Klimburg concludes:

. . . The ability of civil society and news media in democratic societies everywhere to respond to the so-called “fake news phenomenon” leaves me hopeful that the technical vulnerabilities in the wider information ecosystem can be patched. Some of the topics are already being discussed, dealing for instance with algorithmic informational bubbles and the general workings of large social media organizations, and tempered with the need to preserve human rights and above all the freedom of speech. As a result, many thousands or even tens of thousands on new individuals directly and indirectly in the governance of this new domain of human behavior. Many more than that will have been warned by this seeming small detonation of info war, and will tacitly support the efforts of civil society, industry, and government actors that have taken up the fight on their behalf. They will reinforce the battle taking place for the future of cyberspace and the free web, which is nothing less than the struggle for the heart of modern democratic society. It will not be a struggle that passes quicky—but just as singular individuals in previous decades made a crucial difference, we can all do so today.

Can the downward slope of trust be reversed?

Social media, reality TV, and 24-hour news, I’m afraid, have turned much of America into one giant shouting match. We need to learn to talk—even to listen—and not just try to out-shout each other. Following the Parkland school shooting, we were once again urged to “see something, say something.” That may be good, but it works best in a community of real connections and high trust. There is significant danger that such a slogan can also lead to distrust, suspicion, judgmentalism and growing fear Combining my starting point of the diminishing confidence in institutions with the tragedies of a school shooting, the fears of technology run amok through artificial intelligence and a darkening Web, how can we restore trust? . . . in our communities? . . . in our neighbors (literal and virtual)? . . . in our institutions?

As historian David Kennedy and former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice recently urged on the PBS program “American Creed,” we are losing something precious when we let slip through our fingers the great Ideas of government by the people and “out of many, one” that still define the American experiment. Are we forever committed to a downward slope or can trust in each other and our institutions be restored?

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: March 65, 2018 Accessed 3,057 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: General / Topics: Censorship • Change • Demographics • Ethics • Government • Information • Information Management • Internet • Media • Opinion research • Policy • Science & Technology • Social Movements • Trends

Trust

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: March 65, 2018

Can we stop the downward slide?…

Back in May of 2015, I wrote on the issue of trust in an article, “Who Do You Trust?,” making reference to the TV game show by that name, which ran from 1958 to 1962. It was interesting to review that article myself, considering some issues that have appeared in the news since then. Given current circumstances and spurred by a couple of books I’ve been reading recently, it seemed to be a good time to return to the topic of trust.

America’s declining confidence in social institutions

Research by the Gallup organization since 1973 shows a steady decline in the confidence of Americans in our major social institutions. For the purposes of this article, it seems fair to equate the term “trust” with “confidence,” the word Gallup uses in soliciting opinions. The chart below comes from my report on Religion in America, so it shows how organized religion compares to all institutions included in the survey (16 in 2017).

The data on this and the following chart represent selection of either a “Great deal” or “Quite a lot” of confidence,

representing the top two scores on a five-point rating scale, from “Great deal” to “None.”

While the drop in organized religion is significant, it is the general decline for all institutions over more than four decades that is central to my point here. (You can read more analysis on organized religion in my Religion in America report).

You can see from the chart above that only the military and small business had strong majority support in 2017 (combining those who responded a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence). Both were at a level slightly above their long-term average (the military since the survey began in 1973, small business on a continuous basis since 2007).

“The Police” is the only other institution with majority support, but much less than the first two. Given the media coverage of protests against police in several high profile situations in the past few years, it is remarkable that confidence has not wavered significantly over the 25 years it has been included—the score of 57% in 2017 matches the average over that time.

Organized religion first fell below majority confidence in 2002 and has stayed there since 2010. You can see from the list that half of the institutions measured are viewed with confidence by no more than one-third of those surveyed, including institutions that should be solid foundations of American society.

The continued downward arc of confidence levels led me to consider several specific examples, spurred by recent reading and one news report the other day:

The Second Amendment: Lost Trust?

The details of the debate over the necessary response to the recent school shooting in Parkland, Florida are beyond the scope of this article—and go well beyond gun control itself. Shortly before that tragedy occurred, I was browsing the New Books section of my local library and found Scalia Speaks, a collection of speeches by Antonin Scalia, late Supreme Court Justice, edited by his son, Christopher, and Edward Whelan, who clerked for Justice Scalia. (While on opposite ends of the judicial spectrum, the foreword to the book was written by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who developed a close friendship with Scalia while both served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in the 1980s. Both would meet again as justices on the U.S. Supreme Court.)

In a 2007 speech to Le Cercle, Justice Scalia addressed differences between American and European values. (Le Cercle is a group of European and American parliamentarians, diplomats, intelligence officials, bankers, and business leaders founded in the 1950s by West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer and French prime minister Antoine Pinay). In part of the speech, he walked through the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution—as an example of the differences in viewpoint and values.

While my point here is to talk about the Second Amendment and trust, it could be helpful to listen to Justice Scalia’s discussion of the First Amendment to get a sense of perspective (especially given the sensitivity today on many university campuses to protect students from speech that makes them uncomfortable, as well as the subject of Cybercrime in the second paragraph, both of which I will touch on later):

The First Amendment, often considered by Americans to be the proverbial jewel in the crown that is the U.S. Constitution, staunchly defends freedom of speech. Americans have proven themselves to be willing to protect that freedom against all manner of detractors; willing to display the thick skin that the First Amendment requires, and to recognize that the right to speak is far more important than a right not to be offended by what is spoken. Thus, when the Nazi Party of America planned to march through the streets of Skokie, Illinois, in 1977, its right to do so was supported by the American Civil Liberties Union and protected by the courts despite the repugnancy of its message.

To be sure, Europeans also value the freedom of speech and its importance to a functioning democracy. But they are far more willing to suppress a speaker’s message when it might prove inflammatory to the populace at large, or even when it might be thought to erode national culture. Thus, laws such as those banning pro-Nazi propaganda that would never pass constitutional muster in the United State are not atypical in Europe. In November 2002, the Council of Europe approved an “Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime” that would make it illegal to distribute anything online which “advocates, promotes or incites hatred [or] discrimination.” A spokesman for the United States Department of Justice said (quite correctly) that his county could not be part to such a treaty because of the First Amendment.