Making Information Make Sense

InfoMatters

Category: Religion / Topics: Bible • Change • Demographics • Religion • Science & Technology • Statistics • Trends

Generation Z

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: February 47, 2018

The first post-Christian generation in America?…

One of the most recent reports from the Barna Group is entitled “Atheism Doubles Among Generation Z.” The report shows the deepening divide on core beliefs, especially in matters of faith, that will require a hard look by older generations seeking to bridge the divide. One of the first steps, of course, is recognizing that there is a divide and describing it in the most accurate and helpful terms. Let’s look at the data first, then I will conclude with the challenges I see.

In this blog, I will present a summary of the Barna report. One of the two graphs used below is already included in the latest update to the Religion in America page on my website. I will also be adding more charts based on the Barna study to the detailed PowerPoint® version of Religion in America, which is used in presentations. After reading this summary, I encourage you to read the full report on the Barna website. After conducting a webinar about the research, Barna has also posted a response to questions, which contains additional detail that I will include in future blogs and/or the Religion in America presentation.

The Generations

“Generation Z” is the newest generation, and because the oldest members are now teens, they are being included in public opinion research, such as this study. That is significant. For years now, we have talked about changes seen among Millennials, but they are leaving the teens and many are in their early thirties (already!).

The generation markers that have commonly been assigned for these social groups in this type of report do not correspond with the five-year brackets typically used in U.S. Census Bureau reports, Neilsen ratings, and many other demographic reports (i.e., 20-24, 25-29, etc. by age). If a researcher asks respondents for a birth year or age, the results can be reported either by traditional brackets or by generational groups.

Here are the generation labels and birth date ranges used by Barna. At the end of this post I have included a list of generations used by Pew, Gallup and a few other researches, which shows agreement on Baby Boomers, but some differences in labels and age ranges for the other generations.

- Generation Z – 1999-2015 (roughly 3-18 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Millennials – 1984-1998 (roughly 19-33 years old at beginning of 2018)

- Generation X – 1965-1983 (roughly 34-52 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Baby Boomers – 1946-1964 (roughly 53-71 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Elders – born 1945 or earlier (72 years old or more at the beginning of 2018)

Major take-aways from the Barna study:

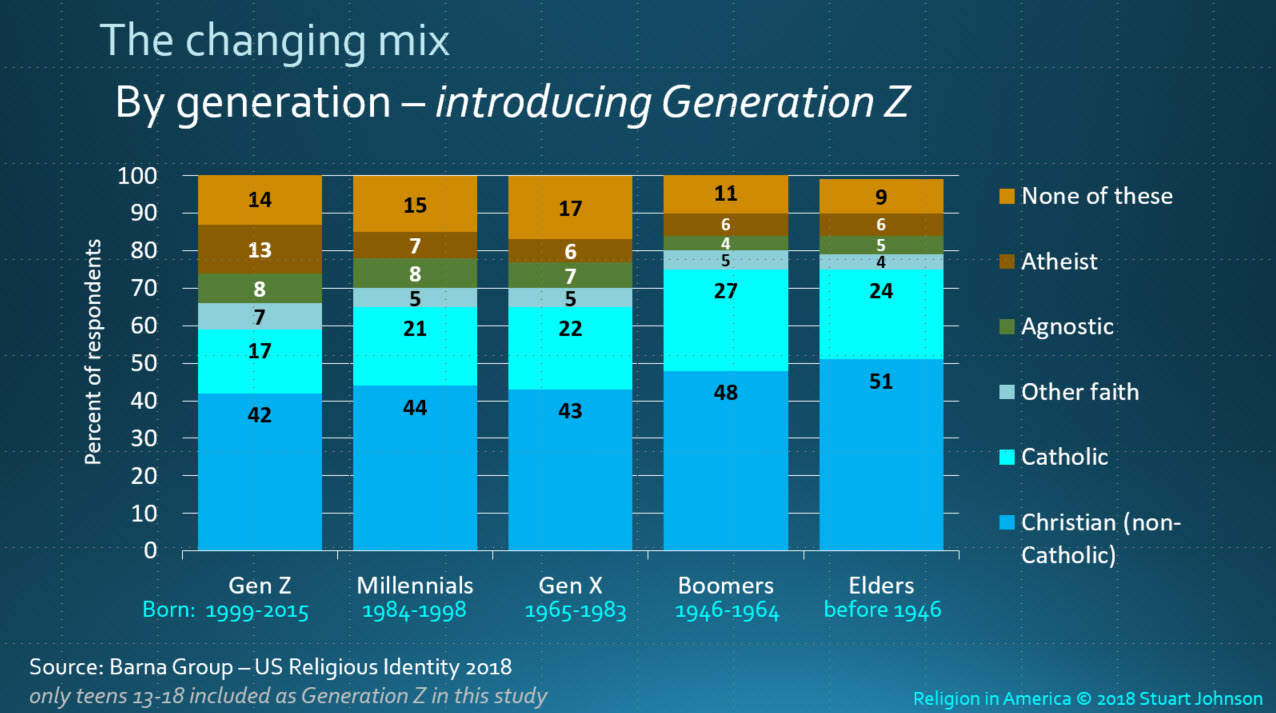

- The percentage of teens who identify as atheist is double that of the general population.

- The “rise of the nones” (those claiming no religious affiliation) which has risen dramatically since 2000, also increases across generations, reaching more than one-third for Generation Z.

- The biggest barrier to faith among non-Christian Millennials and Gen Z is the problem of evil—how can a good God allow evil and suffering? —followed by seeing Christians as hypocrites.

- The biggest barrier to faith for non-Christian Gen X and Boomers is the feeling that Christians are hypocrites, followed by the problem of evil.

- Nearly half of teens, on par with Millennials, want factual evidence to support their beliefs.

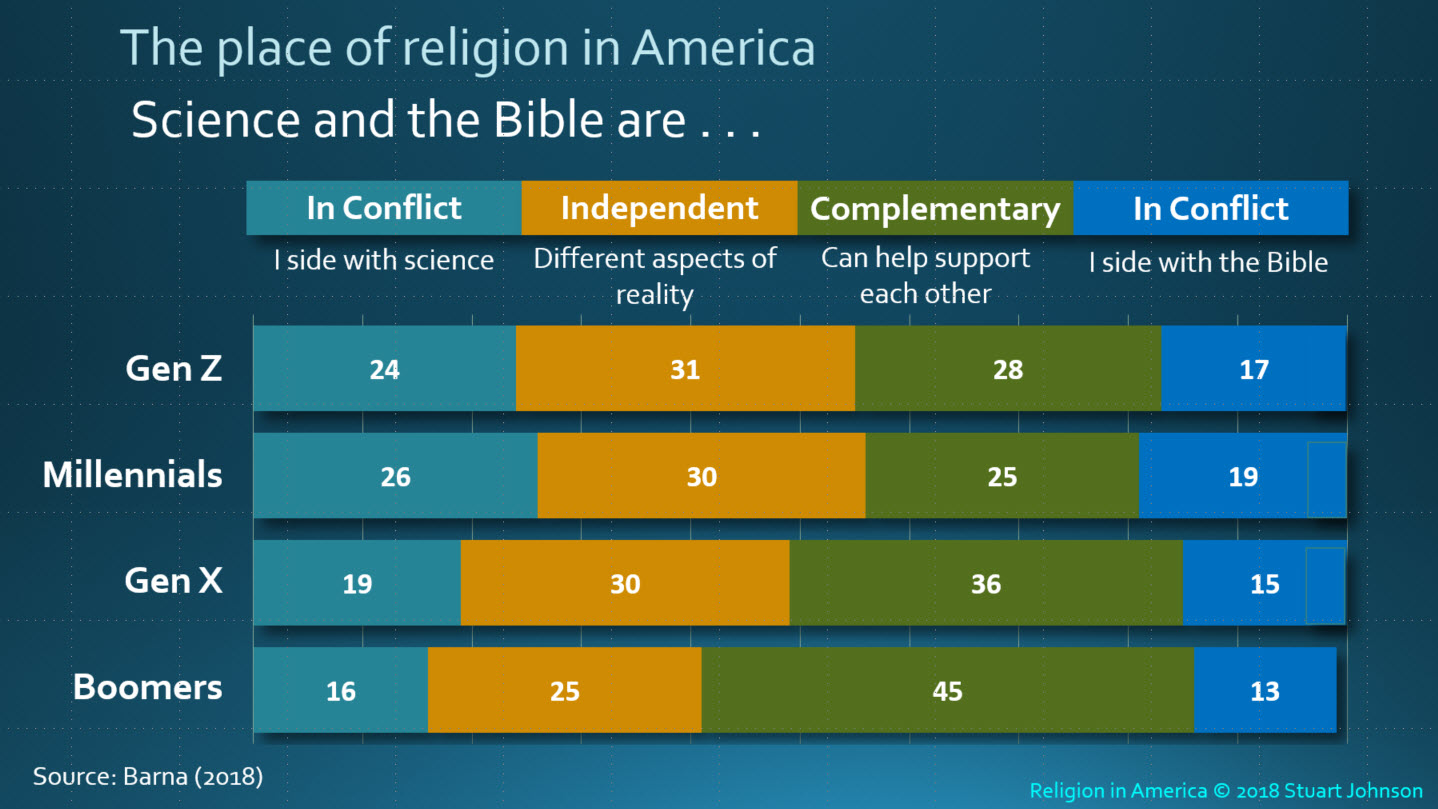

- One third of teens consider science and the Bible to be independent, while nearly half of Boomers see science and the Bible as complementary.

- Gen Z and Millennials see more conflicts between the Bible and science than do Gen X or Boomers (41% versus 29%). While more side with science—by a seven point margin—the number who side with the Bible is greater than the older generations.

- While churchgoing teens have a positive view of the church’s impact on their lives (“find answers,” “relevant”), half of churchgoing teens say the church seems to reject much of what science tells us.

- Among teens who do not feel church attendance is important, six in ten say it is not relevant and nearly a third say they can teach themselves what they need to know.

The indented text that follows represents excerpts from the Barna report. See the full report for the full text and all the charts.

Introduction

It may come as no surprise that the influence of Christianity in the United States is waning. Rates of church attendance, religious affiliation, belief in God, prayer and Bible-reading have been dropping for decades. Americans’ beliefs are becoming more post-Christian and, concurrently, religious identity is changing. . . .

Enter Generation Z: Born between 1999 and 2015, they are the first truly “post-Christian” generation. More than any other generation before them, Gen Z does not assert a religious identity. They might be drawn to things spiritual, but with a vastly different starting point from previous generations, many of whom received a basic education on the Bible and Christianity. And it shows: The percentage of Gen Z that identifies as atheist is double that of the U.S. adult population.

Atheism on the Rise

Chart from the Religion in America report (adapted from the chart in the Barna report)

For Gen Z, “atheist” is no longer a dirty word: The percentage of teens who identify as such is double that of the general population (13% vs. 6% of all adults). The proportion that identifies as Christian likewise drops from generation to generation. Three out of four Boomers are Protestant or Catholic Christians (75%), while just three in five 13- to 18-year-olds say they are some kind of Christian (59%).

In each of the following sections, a detailed chart will be found in the Barna Report and in my full Religion in America presentation. Some charts on the Religion in America page show trends for similar topics from surveys by Gallup, the Pew Research Center, Barna and other sources.

Barriers to Faith

So what has led to this precipitous falling off? Barna asked non-Christians of all ages about their biggest barriers to faith. Gen Z nonbelievers have much in common with their older counterparts in this regard, but a few differences stand out. Teens, along with young adults, are more likely than older Americans to say the problem of evil and suffering is a deal breaker for them. It appears that today’s youth, like so many throughout history, struggle to find a compelling argument for the existence of both evil and a good and loving God.

Interestingly, Gen Z nonbelievers appear less likely than non-Christian adults to cite Christians’ hypocrisy as a significant barrier—but just as likely to say they have personally had a bad experience with Christians or a church. On a separate but related question, teens overall are somewhat less inclined than U.S. adults to strongly agree that “religious people are judgmental” (17% vs. 24% all adults). Current political issues, especially LGBTQ rights, poverty and immigration policy, may impact whether this perception holds as Gen Z gets older.

An increasingly elusive truth

More than one-third of Gen Z (37%) believes it is not possible to know for sure if God is real, compared to 32 percent of all adults. On the other side of the coin, teens who do believe one can know God exists are less likely than adults to say they are very convinced that is true (54% vs. 64% all adults who believe in God). For many teens, truth seems relative at best and, at worst, altogether unknowable.

Their lack of confidence is on pace with the broader culture’s all-out embrace of relativism. More than half of all Americans, both teens (58%) and adults (62%), agree with the statement “Many religions can lead to eternal life; there is no ‘one true religion.’” There’s a sense among Gen Z that what’s true for someone else may not be “true for me”; they are much less apt than older adults (especially Boomers, 85%) to agree that “a person can be wrong about something that they sincerely believe in” (66%). For a considerable minority of teens, sincerely believing something makes it true.

At the same time, some are leaning toward sincerity as a marker for truth, more are leaning hard in the other direction. Nearly half of teens, on par with Millennials, say “I need factual evidence to support my beliefs” (46%)—which helps to explain their uneasiness with the relationship between science and the Bible (chart below). Significantly fewer teens and young adults (28% and 25%) than Gen X and Boomers (36% and 45%) see the two as complementary.

Chart from the Religion in America presentation (adapted from the chart in the Barna report)

Positive view of church, but few attend

Among Gen Z churchgoers (those who have attended one or more worship services within the past month), perceptions of church tend to be more positive than negative. Strong majorities of churched teens say that church “is a place to find answers to live a meaningful life” (82%) and “is relevant to my life” (82%), that “I can ‘be myself’ in church” (77%) and that “people at church are tolerant of those with different beliefs” (63%). Negative perceptions have significant currency, however. Half of churchgoing teens say “the church seems to reject much of what science tells us about the world” (49%) and one-third that “the church is overprotective of teenagers” (38%) or “the people at church are hypocritical” (36%). Further, one-quarter claims “the church is not a safe place to express doubts” (27%) or that the teaching they are exposed to is “rather shallow” (24%).

More than half of Gen Z says church involvement is either “not too” (27%) or “not at all” important (27%). Only one in five says attending church is “very important” to them (20%), the least popular of the four options.

Why is church unimportant? Non-Christians and self-identified Christians have different reasons. Among those who say attending church is not important to them, three out of five Christian teens say “I find God elsewhere” (61%), while about the same proportion of non-Christians says “church is not relevant to me personally” (64%). The non-Christians’ most popular answer makes sense (they’re not Christians, after all), but Christians’ reasoning is an indicator that at least some churches are not helping to facilitate teens’ transformative connection with God.

Conclusion: A Challenge to Evangelicals

I believe this Barna report clearly demonstrates the need for some soul-searching by Christians who wish to bridge the generations. This should begin by affirming exactly what the Gospel of Jesus Christ is, particularly for those who embrace both the Great Commandments (loving God and neighbor) and the Great Commission (evangelizing, discipling the world) as core components of their beliefs.

How much of what older believers cling to is cultural baggage rather than the central message of God’s creation, care and redemptive purposes? And what about the truth claims made by Jesus himself, as Son of God (John 10:35-37, among many other references in the Bible) and as “the Way, the Truth, and the Life (John 14:6)?

Equally important, how are younger generations affected by their culture—and how does that impact communication across generations? What is driving so many away from faith (or at least from organized religion)?

Compounding the generational divide are at least two areas of concern I have observed (and talked about in other blogs).

- Science and Faith. The assumption of a fundamental and necessary conflict between the Bible and science is itself fundamentally unnecessary (with rigorous adherence to scientific method). The Bible is not a science text book. Instead, it describes a much broader narrative that presents God as creator, sustainer and redeemer. Science rightfully discovers and explains (as best it can with its current understanding) God’s creation—whether it recognizes it as such or not—even as the known universe expands exponentially. Science, as well as “religion” and all other human pursuits, operate inside the larger reality of God’s creation.

The Barna survey shows increasingly younger generations siding with science when there are perceived conflicts with the Bible, it might be expected that those siding with the Bible would be shrinking. Yet, it is not. It is the middle (science and the Bible as independent or complementary) that shrinks, from 70% among Boomers to 55-59% among Millennials and Gen Z.

This is worth further exploration, but I suspect that the growth of those siding with the Bible is influenced by what can broadly be called fundamentalism, with a strong absolutely literal approach to the Bible that leads to creationism (young earth) and general distrust of science, including climate-change denial (as opposed to a milder skepticism expressed by others arising from the entanglement of politics with science). This movement may have found traction through the growth of home schooling, Christian academies, and similar settings that provide an incubator for this worldview—which leads to the second observation:

- Evangelicalism. Especially since the 1980s, with the rise of the politically motivated “Religious Right” and most noticeably since the 2000 presidential election in the United States, the term “evangelical” has lost its meaning. The national media, especially in political reporting and polling, began to use “evangelical” as a catch-all description conflating evangelicals with all conservative expressions of Christian faith outside of mainline Protestantism. Seen as being outside the “mainstream,” the term “evangelical” can been used in a derogatory manner. (See some of the charts in my Religion in America report that track several related trends).

There is much frustration among those who have called themselves evangelical, with some now avoiding the term, preferring instead to be called simply a “Christ-Follower” or searching for a new identification. The problem, of course, is that any label can be coopted by outside forces, and you’re right back to the situation seen now. It is unsettling when a label you have been comfortable with—and which had a distinctive meaning for so many years—is highjacked or corrupted.

Is this just a family squabble that means little to those outside the fold? While that may appear to be the case, there is much that evangelicals need to distance themselves from to recapture what it means to be a genuine Christ-follower in America and the world today. It requires, it seems to me, the maintenance of a high view of the Bible as the written Word of God, itself part of the greater Word spoken by God through creation and the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, and rediscovering their role in carrying that redemptive message to an increasingly disengaged, even hostile world. It means celebrating the life of the mind and heart as people created in God’s image.

Considering how to be effective in a post-Christian era and how to bridge the generations could be the beginning of a renewed vision and identify for American evangelicals.

I encourage you to read the full Generation Z report on the Barna website. After conducting a webinar about the research, Barna has also posted a response to questions, which contains additional detail that I will include in future blogs and/or the Religion in America presentation. For a summary of trends over recent decades reported by Barna, Gallup, Pew and other researchers, see the Religion in America page on this site.

Here are the generation labels and birth date ranges used by Barna, along with variations in names and/or date ranges from Pew, Gallup and three more cited in an article on ThoughtCo: Neil Howe and William Strauss (HS), from their book, “Generations”; Population Reference Bureau (PRB); and The Center for Generational Kinetics(CGK)

- Generation Z – 1999-2015 (roughly 3-18 years old at the beginning of 2018)

Other researchers start 1996 to 2000, not all have shown precise end date (“present”)- PEW: same name and dates

- GALLUP: same name, but 1999 to “present”

- HS: Gen Z or New Silent Generation – 2000 to present

- PRB: Not listed yet

- CGK: Gen Z, iGen, or Centennials – 1996 to present

- Millennials – 1984-1998 (roughly 19-33 years old at beginning of 2018)

Other researchers cover 1977-2001- PEW: same name, but 1981-1998

- GALLUP: same name, but 1980-1996

- HS: Millennials or Generation Y – 1980-2000

- PRB: New Boomers – 1983-2001

- CGK: Millennials or Generation Y - 1977-1995

- Generation X – 1965-1983 (roughly 34-52 years old at the beginning of 2018)

Other researches all start in 1965, but end 1976-1982- PEW: same name, but 1965-1980

- GALLUP: same name, but 1965-1979

- HS: Gen X or Thirteeners - 1965-1979

- PRB: same name, but 1965-1982

- CGK: Same name, but 1965-1976

- Baby Boomers – 1946-1964 (roughly 53-71 years old at the beginning of 2018)

This is the only generation where all researchers agree on the name and dates

- Elders – born 1945 or earlier (72 years old or more at the beginning of 2018)

Other researches all end in 1945, but start at different points and may subdivide into two or more smaller cohorts- PEW: Silent Generation (1928-1945), Greatest Generation (1901-1927)

- GALLUP: Traditionalists – 1945 or earlier

- HS: Silent Generation (1925-1945), G.I. Generation (1900-1924)

- PRB: Lucky Few (1929-1945), Good Warriors (1909-1928), Hard Timers (1890-1908), New Worlders (1871-1889)

- CKG: Traditionalists or Silent Generation – 1945 or earlier

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: February 47, 2018 Accessed 17,355 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: Religion / Topics: Bible • Change • Demographics • Religion • Science & Technology • Statistics • Trends

Generation Z

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: February 47, 2018

The first post-Christian generation in America?…

One of the most recent reports from the Barna Group is entitled “Atheism Doubles Among Generation Z.” The report shows the deepening divide on core beliefs, especially in matters of faith, that will require a hard look by older generations seeking to bridge the divide. One of the first steps, of course, is recognizing that there is a divide and describing it in the most accurate and helpful terms. Let’s look at the data first, then I will conclude with the challenges I see.

In this blog, I will present a summary of the Barna report. One of the two graphs used below is already included in the latest update to the Religion in America page on my website. I will also be adding more charts based on the Barna study to the detailed PowerPoint® version of Religion in America, which is used in presentations. After reading this summary, I encourage you to read the full report on the Barna website. After conducting a webinar about the research, Barna has also posted a response to questions, which contains additional detail that I will include in future blogs and/or the Religion in America presentation.

The Generations

“Generation Z” is the newest generation, and because the oldest members are now teens, they are being included in public opinion research, such as this study. That is significant. For years now, we have talked about changes seen among Millennials, but they are leaving the teens and many are in their early thirties (already!).

The generation markers that have commonly been assigned for these social groups in this type of report do not correspond with the five-year brackets typically used in U.S. Census Bureau reports, Neilsen ratings, and many other demographic reports (i.e., 20-24, 25-29, etc. by age). If a researcher asks respondents for a birth year or age, the results can be reported either by traditional brackets or by generational groups.

Here are the generation labels and birth date ranges used by Barna. At the end of this post I have included a list of generations used by Pew, Gallup and a few other researches, which shows agreement on Baby Boomers, but some differences in labels and age ranges for the other generations.

- Generation Z – 1999-2015 (roughly 3-18 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Millennials – 1984-1998 (roughly 19-33 years old at beginning of 2018)

- Generation X – 1965-1983 (roughly 34-52 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Baby Boomers – 1946-1964 (roughly 53-71 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Elders – born 1945 or earlier (72 years old or more at the beginning of 2018)

Major take-aways from the Barna study:

- The percentage of teens who identify as atheist is double that of the general population.

- The “rise of the nones” (those claiming no religious affiliation) which has risen dramatically since 2000, also increases across generations, reaching more than one-third for Generation Z.

- The biggest barrier to faith among non-Christian Millennials and Gen Z is the problem of evil—how can a good God allow evil and suffering? —followed by seeing Christians as hypocrites.

- The biggest barrier to faith for non-Christian Gen X and Boomers is the feeling that Christians are hypocrites, followed by the problem of evil.

- Nearly half of teens, on par with Millennials, want factual evidence to support their beliefs.

- One third of teens consider science and the Bible to be independent, while nearly half of Boomers see science and the Bible as complementary.

- Gen Z and Millennials see more conflicts between the Bible and science than do Gen X or Boomers (41% versus 29%). While more side with science—by a seven point margin—the number who side with the Bible is greater than the older generations.

- While churchgoing teens have a positive view of the church’s impact on their lives (“find answers,” “relevant”), half of churchgoing teens say the church seems to reject much of what science tells us.

- Among teens who do not feel church attendance is important, six in ten say it is not relevant and nearly a third say they can teach themselves what they need to know.

The indented text that follows represents excerpts from the Barna report. See the full report for the full text and all the charts.

Introduction

It may come as no surprise that the influence of Christianity in the United States is waning. Rates of church attendance, religious affiliation, belief in God, prayer and Bible-reading have been dropping for decades. Americans’ beliefs are becoming more post-Christian and, concurrently, religious identity is changing. . . .

Enter Generation Z: Born between 1999 and 2015, they are the first truly “post-Christian” generation. More than any other generation before them, Gen Z does not assert a religious identity. They might be drawn to things spiritual, but with a vastly different starting point from previous generations, many of whom received a basic education on the Bible and Christianity. And it shows: The percentage of Gen Z that identifies as atheist is double that of the U.S. adult population.

Atheism on the Rise

Chart from the Religion in America report (adapted from the chart in the Barna report)

For Gen Z, “atheist” is no longer a dirty word: The percentage of teens who identify as such is double that of the general population (13% vs. 6% of all adults). The proportion that identifies as Christian likewise drops from generation to generation. Three out of four Boomers are Protestant or Catholic Christians (75%), while just three in five 13- to 18-year-olds say they are some kind of Christian (59%).

In each of the following sections, a detailed chart will be found in the Barna Report and in my full Religion in America presentation. Some charts on the Religion in America page show trends for similar topics from surveys by Gallup, the Pew Research Center, Barna and other sources.

Barriers to Faith

So what has led to this precipitous falling off? Barna asked non-Christians of all ages about their biggest barriers to faith. Gen Z nonbelievers have much in common with their older counterparts in this regard, but a few differences stand out. Teens, along with young adults, are more likely than older Americans to say the problem of evil and suffering is a deal breaker for them. It appears that today’s youth, like so many throughout history, struggle to find a compelling argument for the existence of both evil and a good and loving God.

Interestingly, Gen Z nonbelievers appear less likely than non-Christian adults to cite Christians’ hypocrisy as a significant barrier—but just as likely to say they have personally had a bad experience with Christians or a church. On a separate but related question, teens overall are somewhat less inclined than U.S. adults to strongly agree that “religious people are judgmental” (17% vs. 24% all adults). Current political issues, especially LGBTQ rights, poverty and immigration policy, may impact whether this perception holds as Gen Z gets older.

An increasingly elusive truth

More than one-third of Gen Z (37%) believes it is not possible to know for sure if God is real, compared to 32 percent of all adults. On the other side of the coin, teens who do believe one can know God exists are less likely than adults to say they are very convinced that is true (54% vs. 64% all adults who believe in God). For many teens, truth seems relative at best and, at worst, altogether unknowable.

Their lack of confidence is on pace with the broader culture’s all-out embrace of relativism. More than half of all Americans, both teens (58%) and adults (62%), agree with the statement “Many religions can lead to eternal life; there is no ‘one true religion.’” There’s a sense among Gen Z that what’s true for someone else may not be “true for me”; they are much less apt than older adults (especially Boomers, 85%) to agree that “a person can be wrong about something that they sincerely believe in” (66%). For a considerable minority of teens, sincerely believing something makes it true.

At the same time, some are leaning toward sincerity as a marker for truth, more are leaning hard in the other direction. Nearly half of teens, on par with Millennials, say “I need factual evidence to support my beliefs” (46%)—which helps to explain their uneasiness with the relationship between science and the Bible (chart below). Significantly fewer teens and young adults (28% and 25%) than Gen X and Boomers (36% and 45%) see the two as complementary.

Chart from the Religion in America presentation (adapted from the chart in the Barna report)

Positive view of church, but few attend

Among Gen Z churchgoers (those who have attended one or more worship services within the past month), perceptions of church tend to be more positive than negative. Strong majorities of churched teens say that church “is a place to find answers to live a meaningful life” (82%) and “is relevant to my life” (82%), that “I can ‘be myself’ in church” (77%) and that “people at church are tolerant of those with different beliefs” (63%). Negative perceptions have significant currency, however. Half of churchgoing teens say “the church seems to reject much of what science tells us about the world” (49%) and one-third that “the church is overprotective of teenagers” (38%) or “the people at church are hypocritical” (36%). Further, one-quarter claims “the church is not a safe place to express doubts” (27%) or that the teaching they are exposed to is “rather shallow” (24%).

More than half of Gen Z says church involvement is either “not too” (27%) or “not at all” important (27%). Only one in five says attending church is “very important” to them (20%), the least popular of the four options.

Why is church unimportant? Non-Christians and self-identified Christians have different reasons. Among those who say attending church is not important to them, three out of five Christian teens say “I find God elsewhere” (61%), while about the same proportion of non-Christians says “church is not relevant to me personally” (64%). The non-Christians’ most popular answer makes sense (they’re not Christians, after all), but Christians’ reasoning is an indicator that at least some churches are not helping to facilitate teens’ transformative connection with God.

Conclusion: A Challenge to Evangelicals

I believe this Barna report clearly demonstrates the need for some soul-searching by Christians who wish to bridge the generations. This should begin by affirming exactly what the Gospel of Jesus Christ is, particularly for those who embrace both the Great Commandments (loving God and neighbor) and the Great Commission (evangelizing, discipling the world) as core components of their beliefs.

How much of what older believers cling to is cultural baggage rather than the central message of God’s creation, care and redemptive purposes? And what about the truth claims made by Jesus himself, as Son of God (John 10:35-37, among many other references in the Bible) and as “the Way, the Truth, and the Life (John 14:6)?

Equally important, how are younger generations affected by their culture—and how does that impact communication across generations? What is driving so many away from faith (or at least from organized religion)?

Compounding the generational divide are at least two areas of concern I have observed (and talked about in other blogs).

- Science and Faith. The assumption of a fundamental and necessary conflict between the Bible and science is itself fundamentally unnecessary (with rigorous adherence to scientific method). The Bible is not a science text book. Instead, it describes a much broader narrative that presents God as creator, sustainer and redeemer. Science rightfully discovers and explains (as best it can with its current understanding) God’s creation—whether it recognizes it as such or not—even as the known universe expands exponentially. Science, as well as “religion” and all other human pursuits, operate inside the larger reality of God’s creation.

The Barna survey shows increasingly younger generations siding with science when there are perceived conflicts with the Bible, it might be expected that those siding with the Bible would be shrinking. Yet, it is not. It is the middle (science and the Bible as independent or complementary) that shrinks, from 70% among Boomers to 55-59% among Millennials and Gen Z.

This is worth further exploration, but I suspect that the growth of those siding with the Bible is influenced by what can broadly be called fundamentalism, with a strong absolutely literal approach to the Bible that leads to creationism (young earth) and general distrust of science, including climate-change denial (as opposed to a milder skepticism expressed by others arising from the entanglement of politics with science). This movement may have found traction through the growth of home schooling, Christian academies, and similar settings that provide an incubator for this worldview—which leads to the second observation:

- Evangelicalism. Especially since the 1980s, with the rise of the politically motivated “Religious Right” and most noticeably since the 2000 presidential election in the United States, the term “evangelical” has lost its meaning. The national media, especially in political reporting and polling, began to use “evangelical” as a catch-all description conflating evangelicals with all conservative expressions of Christian faith outside of mainline Protestantism. Seen as being outside the “mainstream,” the term “evangelical” can been used in a derogatory manner. (See some of the charts in my Religion in America report that track several related trends).

There is much frustration among those who have called themselves evangelical, with some now avoiding the term, preferring instead to be called simply a “Christ-Follower” or searching for a new identification. The problem, of course, is that any label can be coopted by outside forces, and you’re right back to the situation seen now. It is unsettling when a label you have been comfortable with—and which had a distinctive meaning for so many years—is highjacked or corrupted.

Is this just a family squabble that means little to those outside the fold? While that may appear to be the case, there is much that evangelicals need to distance themselves from to recapture what it means to be a genuine Christ-follower in America and the world today. It requires, it seems to me, the maintenance of a high view of the Bible as the written Word of God, itself part of the greater Word spoken by God through creation and the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, and rediscovering their role in carrying that redemptive message to an increasingly disengaged, even hostile world. It means celebrating the life of the mind and heart as people created in God’s image.

Considering how to be effective in a post-Christian era and how to bridge the generations could be the beginning of a renewed vision and identify for American evangelicals.

I encourage you to read the full Generation Z report on the Barna website. After conducting a webinar about the research, Barna has also posted a response to questions, which contains additional detail that I will include in future blogs and/or the Religion in America presentation. For a summary of trends over recent decades reported by Barna, Gallup, Pew and other researchers, see the Religion in America page on this site.

Here are the generation labels and birth date ranges used by Barna, along with variations in names and/or date ranges from Pew, Gallup and three more cited in an article on ThoughtCo: Neil Howe and William Strauss (HS), from their book, “Generations”; Population Reference Bureau (PRB); and The Center for Generational Kinetics(CGK)

- Generation Z – 1999-2015 (roughly 3-18 years old at the beginning of 2018)

Other researchers start 1996 to 2000, not all have shown precise end date (“present”)- PEW: same name and dates

- GALLUP: same name, but 1999 to “present”

- HS: Gen Z or New Silent Generation – 2000 to present

- PRB: Not listed yet

- CGK: Gen Z, iGen, or Centennials – 1996 to present

- Millennials – 1984-1998 (roughly 19-33 years old at beginning of 2018)

Other researchers cover 1977-2001- PEW: same name, but 1981-1998

- GALLUP: same name, but 1980-1996

- HS: Millennials or Generation Y – 1980-2000

- PRB: New Boomers – 1983-2001

- CGK: Millennials or Generation Y - 1977-1995

- Generation X – 1965-1983 (roughly 34-52 years old at the beginning of 2018)

Other researches all start in 1965, but end 1976-1982- PEW: same name, but 1965-1980

- GALLUP: same name, but 1965-1979

- HS: Gen X or Thirteeners - 1965-1979

- PRB: same name, but 1965-1982

- CGK: Same name, but 1965-1976

- Baby Boomers – 1946-1964 (roughly 53-71 years old at the beginning of 2018)

This is the only generation where all researchers agree on the name and dates

- Elders – born 1945 or earlier (72 years old or more at the beginning of 2018)

Other researches all end in 1945, but start at different points and may subdivide into two or more smaller cohorts- PEW: Silent Generation (1928-1945), Greatest Generation (1901-1927)

- GALLUP: Traditionalists – 1945 or earlier

- HS: Silent Generation (1925-1945), G.I. Generation (1900-1924)

- PRB: Lucky Few (1929-1945), Good Warriors (1909-1928), Hard Timers (1890-1908), New Worlders (1871-1889)

- CKG: Traditionalists or Silent Generation – 1945 or earlier

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: February 47, 2018 Accessed 17,356 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: Religion / Topics: Bible • Change • Demographics • Religion • Science & Technology • Statistics • Trends

Generation Z

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: February 47, 2018

The first post-Christian generation in America?…

One of the most recent reports from the Barna Group is entitled “Atheism Doubles Among Generation Z.” The report shows the deepening divide on core beliefs, especially in matters of faith, that will require a hard look by older generations seeking to bridge the divide. One of the first steps, of course, is recognizing that there is a divide and describing it in the most accurate and helpful terms. Let’s look at the data first, then I will conclude with the challenges I see.

In this blog, I will present a summary of the Barna report. One of the two graphs used below is already included in the latest update to the Religion in America page on my website. I will also be adding more charts based on the Barna study to the detailed PowerPoint® version of Religion in America, which is used in presentations. After reading this summary, I encourage you to read the full report on the Barna website. After conducting a webinar about the research, Barna has also posted a response to questions, which contains additional detail that I will include in future blogs and/or the Religion in America presentation.

The Generations

“Generation Z” is the newest generation, and because the oldest members are now teens, they are being included in public opinion research, such as this study. That is significant. For years now, we have talked about changes seen among Millennials, but they are leaving the teens and many are in their early thirties (already!).

The generation markers that have commonly been assigned for these social groups in this type of report do not correspond with the five-year brackets typically used in U.S. Census Bureau reports, Neilsen ratings, and many other demographic reports (i.e., 20-24, 25-29, etc. by age). If a researcher asks respondents for a birth year or age, the results can be reported either by traditional brackets or by generational groups.

Here are the generation labels and birth date ranges used by Barna. At the end of this post I have included a list of generations used by Pew, Gallup and a few other researches, which shows agreement on Baby Boomers, but some differences in labels and age ranges for the other generations.

- Generation Z – 1999-2015 (roughly 3-18 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Millennials – 1984-1998 (roughly 19-33 years old at beginning of 2018)

- Generation X – 1965-1983 (roughly 34-52 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Baby Boomers – 1946-1964 (roughly 53-71 years old at the beginning of 2018)

- Elders – born 1945 or earlier (72 years old or more at the beginning of 2018)

Major take-aways from the Barna study:

- The percentage of teens who identify as atheist is double that of the general population.

- The “rise of the nones” (those claiming no religious affiliation) which has risen dramatically since 2000, also increases across generations, reaching more than one-third for Generation Z.

- The biggest barrier to faith among non-Christian Millennials and Gen Z is the problem of evil—how can a good God allow evil and suffering? —followed by seeing Christians as hypocrites.

- The biggest barrier to faith for non-Christian Gen X and Boomers is the feeling that Christians are hypocrites, followed by the problem of evil.

- Nearly half of teens, on par with Millennials, want factual evidence to support their beliefs.

- One third of teens consider science and the Bible to be independent, while nearly half of Boomers see science and the Bible as complementary.

- Gen Z and Millennials see more conflicts between the Bible and science than do Gen X or Boomers (41% versus 29%). While more side with science—by a seven point margin—the number who side with the Bible is greater than the older generations.

- While churchgoing teens have a positive view of the church’s impact on their lives (“find answers,” “relevant”), half of churchgoing teens say the church seems to reject much of what science tells us.

- Among teens who do not feel church attendance is important, six in ten say it is not relevant and nearly a third say they can teach themselves what they need to know.

The indented text that follows represents excerpts from the Barna report. See the full report for the full text and all the charts.

Introduction

It may come as no surprise that the influence of Christianity in the United States is waning. Rates of church attendance, religious affiliation, belief in God, prayer and Bible-reading have been dropping for decades. Americans’ beliefs are becoming more post-Christian and, concurrently, religious identity is changing. . . .

Enter Generation Z: Born between 1999 and 2015, they are the first truly “post-Christian” generation. More than any other generation before them, Gen Z does not assert a religious identity. They might be drawn to things spiritual, but with a vastly different starting point from previous generations, many of whom received a basic education on the Bible and Christianity. And it shows: The percentage of Gen Z that identifies as atheist is double that of the U.S. adult population.

Atheism on the Rise

Chart from the Religion in America report (adapted from the chart in the Barna report)

For Gen Z, “atheist” is no longer a dirty word: The percentage of teens who identify as such is double that of the general population (13% vs. 6% of all adults). The proportion that identifies as Christian likewise drops from generation to generation. Three out of four Boomers are Protestant or Catholic Christians (75%), while just three in five 13- to 18-year-olds say they are some kind of Christian (59%).

In each of the following sections, a detailed chart will be found in the Barna Report and in my full Religion in America presentation. Some charts on the Religion in America page show trends for similar topics from surveys by Gallup, the Pew Research Center, Barna and other sources.

Barriers to Faith

So what has led to this precipitous falling off? Barna asked non-Christians of all ages about their biggest barriers to faith. Gen Z nonbelievers have much in common with their older counterparts in this regard, but a few differences stand out. Teens, along with young adults, are more likely than older Americans to say the problem of evil and suffering is a deal breaker for them. It appears that today’s youth, like so many throughout history, struggle to find a compelling argument for the existence of both evil and a good and loving God.

Interestingly, Gen Z nonbelievers appear less likely than non-Christian adults to cite Christians’ hypocrisy as a significant barrier—but just as likely to say they have personally had a bad experience with Christians or a church. On a separate but related question, teens overall are somewhat less inclined than U.S. adults to strongly agree that “religious people are judgmental” (17% vs. 24% all adults). Current political issues, especially LGBTQ rights, poverty and immigration policy, may impact whether this perception holds as Gen Z gets older.

An increasingly elusive truth

More than one-third of Gen Z (37%) believes it is not possible to know for sure if God is real, compared to 32 percent of all adults. On the other side of the coin, teens who do believe one can know God exists are less likely than adults to say they are very convinced that is true (54% vs. 64% all adults who believe in God). For many teens, truth seems relative at best and, at worst, altogether unknowable.

Their lack of confidence is on pace with the broader culture’s all-out embrace of relativism. More than half of all Americans, both teens (58%) and adults (62%), agree with the statement “Many religions can lead to eternal life; there is no ‘one true religion.’” There’s a sense among Gen Z that what’s true for someone else may not be “true for me”; they are much less apt than older adults (especially Boomers, 85%) to agree that “a person can be wrong about something that they sincerely believe in” (66%). For a considerable minority of teens, sincerely believing something makes it true.

At the same time, some are leaning toward sincerity as a marker for truth, more are leaning hard in the other direction. Nearly half of teens, on par with Millennials, say “I need factual evidence to support my beliefs” (46%)—which helps to explain their uneasiness with the relationship between science and the Bible (chart below). Significantly fewer teens and young adults (28% and 25%) than Gen X and Boomers (36% and 45%) see the two as complementary.

Chart from the Religion in America presentation (adapted from the chart in the Barna report)

Positive view of church, but few attend

Among Gen Z churchgoers (those who have attended one or more worship services within the past month), perceptions of church tend to be more positive than negative. Strong majorities of churched teens say that church “is a place to find answers to live a meaningful life” (82%) and “is relevant to my life” (82%), that “I can ‘be myself’ in church” (77%) and that “people at church are tolerant of those with different beliefs” (63%). Negative perceptions have significant currency, however. Half of churchgoing teens say “the church seems to reject much of what science tells us about the world” (49%) and one-third that “the church is overprotective of teenagers” (38%) or “the people at church are hypocritical” (36%). Further, one-quarter claims “the church is not a safe place to express doubts” (27%) or that the teaching they are exposed to is “rather shallow” (24%).

More than half of Gen Z says church involvement is either “not too” (27%) or “not at all” important (27%). Only one in five says attending church is “very important” to them (20%), the least popular of the four options.

Why is church unimportant? Non-Christians and self-identified Christians have different reasons. Among those who say attending church is not important to them, three out of five Christian teens say “I find God elsewhere” (61%), while about the same proportion of non-Christians says “church is not relevant to me personally” (64%). The non-Christians’ most popular answer makes sense (they’re not Christians, after all), but Christians’ reasoning is an indicator that at least some churches are not helping to facilitate teens’ transformative connection with God.

Conclusion: A Challenge to Evangelicals

I believe this Barna report clearly demonstrates the need for some soul-searching by Christians who wish to bridge the generations. This should begin by affirming exactly what the Gospel of Jesus Christ is, particularly for those who embrace both the Great Commandments (loving God and neighbor) and the Great Commission (evangelizing, discipling the world) as core components of their beliefs.

How much of what older believers cling to is cultural baggage rather than the central message of God’s creation, care and redemptive purposes? And what about the truth claims made by Jesus himself, as Son of God (John 10:35-37, among many other references in the Bible) and as “the Way, the Truth, and the Life (John 14:6)?

Equally important, how are younger generations affected by their culture—and how does that impact communication across generations? What is driving so many away from faith (or at least from organized religion)?

Compounding the generational divide are at least two areas of concern I have observed (and talked about in other blogs).

- Science and Faith. The assumption of a fundamental and necessary conflict between the Bible and science is itself fundamentally unnecessary (with rigorous adherence to scientific method). The Bible is not a science text book. Instead, it describes a much broader narrative that presents God as creator, sustainer and redeemer. Science rightfully discovers and explains (as best it can with its current understanding) God’s creation—whether it recognizes it as such or not—even as the known universe expands exponentially. Science, as well as “religion” and all other human pursuits, operate inside the larger reality of God’s creation.

The Barna survey shows increasingly younger generations siding with science when there are perceived conflicts with the Bible, it might be expected that those siding with the Bible would be shrinking. Yet, it is not. It is the middle (science and the Bible as independent or complementary) that shrinks, from 70% among Boomers to 55-59% among Millennials and Gen Z.

This is worth further exploration, but I suspect that the growth of those siding with the Bible is influenced by what can broadly be called fundamentalism, with a strong absolutely literal approach to the Bible that leads to creationism (young earth) and general distrust of science, including climate-change denial (as opposed to a milder skepticism expressed by others arising from the entanglement of politics with science). This movement may have found traction through the growth of home schooling, Christian academies, and similar settings that provide an incubator for this worldview—which leads to the second observation:

- Evangelicalism. Especially since the 1980s, with the rise of the politically motivated “Religious Right” and most noticeably since the 2000 presidential election in the United States, the term “evangelical” has lost its meaning. The national media, especially in political reporting and polling, began to use “evangelical” as a catch-all description conflating evangelicals with all conservative expressions of Christian faith outside of mainline Protestantism. Seen as being outside the “mainstream,” the term “evangelical” can been used in a derogatory manner. (See some of the charts in my Religion in America report that track several related trends).

There is much frustration among those who have called themselves evangelical, with some now avoiding the term, preferring instead to be called simply a “Christ-Follower” or searching for a new identification. The problem, of course, is that any label can be coopted by outside forces, and you’re right back to the situation seen now. It is unsettling when a label you have been comfortable with—and which had a distinctive meaning for so many years—is highjacked or corrupted.

Is this just a family squabble that means little to those outside the fold? While that may appear to be the case, there is much that evangelicals need to distance themselves from to recapture what it means to be a genuine Christ-follower in America and the world today. It requires, it seems to me, the maintenance of a high view of the Bible as the written Word of God, itself part of the greater Word spoken by God through creation and the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, and rediscovering their role in carrying that redemptive message to an increasingly disengaged, even hostile world. It means celebrating the life of the mind and heart as people created in God’s image.

Considering how to be effective in a post-Christian era and how to bridge the generations could be the beginning of a renewed vision and identify for American evangelicals.

I encourage you to read the full Generation Z report on the Barna website. After conducting a webinar about the research, Barna has also posted a response to questions, which contains additional detail that I will include in future blogs and/or the Religion in America presentation. For a summary of trends over recent decades reported by Barna, Gallup, Pew and other researchers, see the Religion in America page on this site.

Here are the generation labels and birth date ranges used by Barna, along with variations in names and/or date ranges from Pew, Gallup and three more cited in an article on ThoughtCo: Neil Howe and William Strauss (HS), from their book, “Generations”; Population Reference Bureau (PRB); and The Center for Generational Kinetics(CGK)

- Generation Z – 1999-2015 (roughly 3-18 years old at the beginning of 2018)

Other researchers start 1996 to 2000, not all have shown precise end date (“present”)- PEW: same name and dates

- GALLUP: same name, but 1999 to “present”

- HS: Gen Z or New Silent Generation – 2000 to present

- PRB: Not listed yet

- CGK: Gen Z, iGen, or Centennials – 1996 to present

- Millennials – 1984-1998 (roughly 19-33 years old at beginning of 2018)

Other researchers cover 1977-2001- PEW: same name, but 1981-1998

- GALLUP: same name, but 1980-1996

- HS: Millennials or Generation Y – 1980-2000

- PRB: New Boomers – 1983-2001

- CGK: Millennials or Generation Y - 1977-1995

- Generation X – 1965-1983 (roughly 34-52 years old at the beginning of 2018)

Other researches all start in 1965, but end 1976-1982- PEW: same name, but 1965-1980

- GALLUP: same name, but 1965-1979

- HS: Gen X or Thirteeners - 1965-1979

- PRB: same name, but 1965-1982

- CGK: Same name, but 1965-1976

- Baby Boomers – 1946-1964 (roughly 53-71 years old at the beginning of 2018)

This is the only generation where all researchers agree on the name and dates

- Elders – born 1945 or earlier (72 years old or more at the beginning of 2018)

Other researches all end in 1945, but start at different points and may subdivide into two or more smaller cohorts- PEW: Silent Generation (1928-1945), Greatest Generation (1901-1927)

- GALLUP: Traditionalists – 1945 or earlier

- HS: Silent Generation (1925-1945), G.I. Generation (1900-1924)

- PRB: Lucky Few (1929-1945), Good Warriors (1909-1928), Hard Timers (1890-1908), New Worlders (1871-1889)

- CKG: Traditionalists or Silent Generation – 1945 or earlier

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: February 47, 2018 Accessed 17,357 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...