Making Information Make Sense

InfoMatters

Category: Planning / Topics: Government • History • Media • Planning • Research Methodology • Science & Technology • Statistics

A Paradigm Collapses

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: October 304, 2017

Lessons from three decades of the Low-Fat Revolution…

When I had my annual physical recently, my doctor once again extolled the virtues of a low-carb diet, which he has been promoting for some time now. I had followed some of the advice and lost weight, but still had a way to go. This time, I read his handout again and decided to explore the references. The first one I looked at was Low Carb, High Fat by Andreas Eenfeldt, MD, a Swedish doctor and researcher, whose work (and movement) can also be found on www.dietdoctor.com.

The story as told by Dr. Eenfeldt not only confirmed what my own doctor had been saying from a health standpoint. But it also told another story that revealed how the major paradigm shift to the “fear of fat” occurred in 1984 in the U.S. and spread globally under the new mantra of “Low-Fat.” There are lessons here for many other areas of life. What we find is the interplay of competing ideas where the “winner” is determined not by careful and long-term application of scientific method, but through the power of ego, politics, media, and the misuse of statistics to arrive at “consensus.” That is what we will look at here, using the Low-Fat Revolution as a case study.

Since 1984 when the “fear of fat” was widely proclaimed in the United States, we have come to face a global health crisis, with levels of obesity and diabetes skyrocketing. Type 2 diabetes has increased from 30 million worldwide in 1985 to 415 million in 2015, a nearly thirteen-fold increase in the thirty years since “Low-Fat” became the watchword of good health.

At the same time, obesity rates have steadily climbed. (In a 39-minute video from a seminar he gave, Dr. Eenfeldt uses a series of U.S. maps that show how dramatically obesity has increased since the Low-Fat paradigm shift).

I was struck that such a powerful movement could head us so dramatically in the wrong direction. Eenfeldt himself admits to being convinced of the low-fat paradigm early on, though he came to see its failure and worked to correct it.

Puzzles and Paradigm Shifts

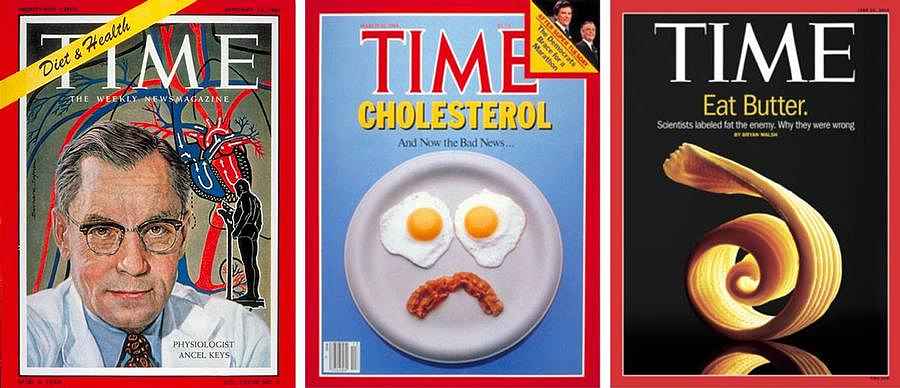

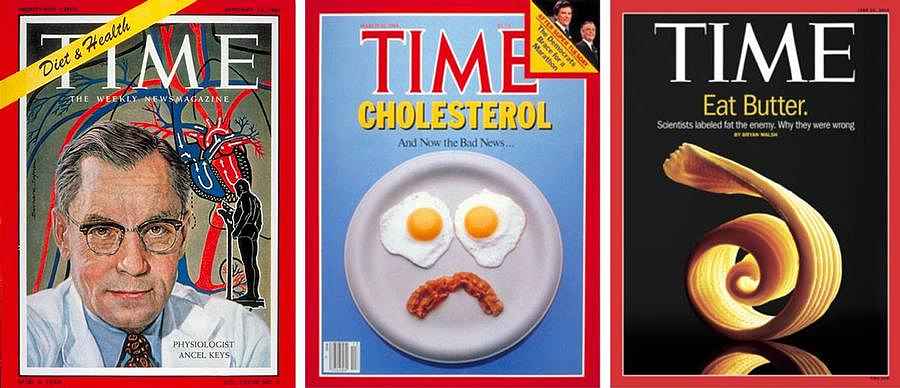

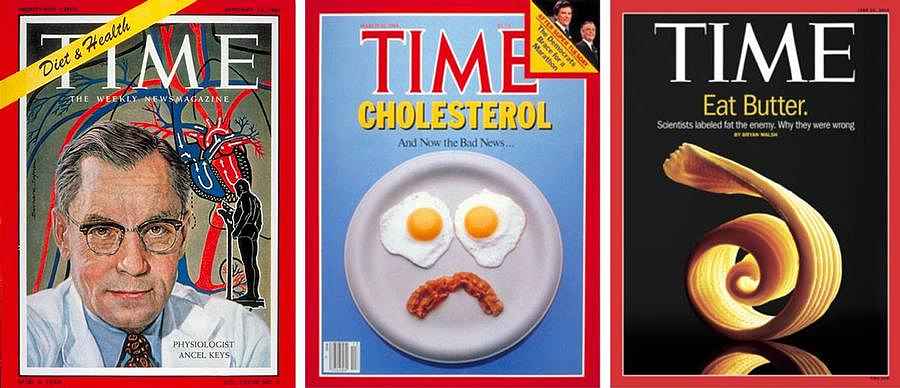

TIME magazine covers tell the story of the “fear of fat” paradigm shift in three quick snapshots. A driving force leading to the Low-Fat Revolution in 1984 was the work of Ancel Keys (left, from a 1961 cover), who claimed that saturated fats in the diet clogged arteries and caused heart disease. While the research led to a drug to lower cholesterol levels, a 1984 cover (center) touted what was then the beginning of public awareness of the benefits of the low-fat approach to nutrition, assumed to produce similar results. By 2014, the “Eat Butter” cover (right) appeared, with the headline “Scientists labeled fat the enemy. Why they were wrong.”

That’s a startling reversal in a very short time. The June 2014 Health Impact News used the 1961 and 2014 covers to illustrate “Time Magazine: We Were Wrong About Saturated Fats,” adding “But don’t expect more mainstream media to follow this repentance on saturated fats.” Indeed, even the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, while backing off from the strong low-fat dictum of earlier guidelines, still shows the considerable influence of the Low-Fat approach touted for much of the past three decades. But, back to the story of the ascendancy and subsequent failure of the Low-Fat Revolution.

Dr. Eenfeldt’s overall assessment is that the adoption of the low-fat approach was a paradigm shift that proved to be wrong, so the paradigm must shift again. This time, he argues, it must shift to a low-carb approach derived from the competing theory of the dangers of starch and sugar. As he explains, these shifts take time and can leave a battlefield strewn with casualties.

In 1962, when Thomas Kuhn wrote the book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, he became the most influential scientific theorist in modern history. He presented a new idea about how scientific progress is made: usually slowly but surely, one piece of the puzzle at a time. But sometimes, the opposite is true. More and more pieces no longer fit into the puzzle, no matter how hard you try. Eventually the contradictions became too many to ignore and explain away. A revolution is inevitable.

The revolution is a paradigm shift. Scientists always interpret their research from their current perception of the world, their paradigm. In revolutions, the old world view is thrown out. A new and better perspective takes over. A new way of piecing together the puzzle. A clearer picture, in which all the pieces fit together. . . .

World view changes in science happen now and then. It is not a strange thing. On the contrary, they are sometimes inevitable. They can happen violently. There could arise an intellectual battle between early adopters and those who stick to the old truth. If the new world view is sufficiently better, it eventually becomes dogma. But it takes years or sometimes decades before the switch is complete. . . .

Not everyone is keen on changing his or her world view, despite how clear the evidence is. They say that a new scientific theory breaks through not by proving dissenters wrong and making them see the light, but because they eventually die out. A new generation who knows the new theory takes over. . . .

If can be difficult to admit “I was wrong” about little things. When it comes to something on which you have built your whole career, that can be difficult to admit even to yourself. Few can handle it. [Eenfeldt, pp 67-70]

In retrospect, the case of the low-fat theory was developed as puzzle pieces appeared to come together, but then as research continued (applying proper scientific method), the pieces began to come apart nearly as quickly, with the new pieces revealing a different picture.

Getting to now: from Hunter-Gatherers to the Fear of Fat

Before getting to the battle of competing theories, it may be helpful to understand Eenfeldt’s portrayal of the relationship between humans and food. In the following description the time-frame, in parentheses, compresses five-million years of human history into a single year:

Hunter-gatherers (364 days) – “We consumed food readily available in nature. . . We received plenty of protein and energy from fat and moderate amounts of indigestible carbohydrates.” Then, in more recent history, three important transformations occurred:

- Agriculture (the last day of the year, New Year’s Eve) – “The agricultural revolution changed everything. It started nine thousand years ago, in today’s Iraq. . . . It arrived in the Nordics some four thousand years ago. . . . The agricultural food was different from what we had eaten before: bread, rice, potatoes, pasta, and other farmed products that mostly consist of starch . . . which is broken down into pure glucose in your stomach.

- Industrial Revolution and the rise of “western food” (15 minutes before midnight on New Year’s Eve) – “The industrial revolution came with factories that produced new types of food. . . .The new white flour could be stored for long periods of time without attracting vermin due to the low nutritional value, since they cannot subsist on pure starch. That meant the flour could be shipped around the world as a trade commodity. . . . The industrial revolution gave us an additional commodity that could be shipped across the world . . . sugar has even more detrimental health effects than starch.

- The Fear of Fat (as the ball drops for the countdown to Midnight) – “The fear of fat and cholesterol exacerbated the changes that had taken place before. This fear resulted in many people eating more of the new food and a slowly emerging endemic disease.”

Eenfeldt goes on to describe what happens when you eat the new food—easily digestible carbohydrates. Starch and sugar quickly produce glucose in the blood, which raises the level of insulin, the body’s fat-storing hormone. Fat does not produce fat in the body, starch and simple carbohydrates do.

Looking for the culprit – heart disease, obesity, diabetes and/or diet

Two competing views of food and its impact on health emerged prior to the TIME magazine cover in 1984. According to researchers like Dr. Eenfeldt, the wrong view won the day.

The trouble with modern food.

You may be thinking, as I did, didn’t people survive quite well in the transition to agriculture? After all, ancient texts are full of examples of people eating grain and bread made from flour or meal ground from various grains. While there are differences between “ancient grains”—which are now touted as healthy—and modern highly refined wheat flour, the agricultural revolution did produce measurable individual and social changes from the very beginning. (See the 2013 paper from the University of Nebraska, “Human Health and the Neolithic Revolution” for an overview of numerous studies).

Seeing the impact of the first transformation—agricultural—the Swedish botanist and physician Carl Linnaeus wrote in his 1751 book Skånska Resa:

Diet has a great effect on the inhabitants of a country. A Laplander, or Saami [denomination of someone from the north of Sweden] lives on meat, fish, and birds, and is small, slim, light, nimble; but a farmer in the south of Sweden, in the plains of Skåne, who eats a lot of buckwheat porridge, and whose food consists chiefly of vegetabilibus farinaceis (vegetable flour dishes), grows big, coarse, stout, strong, sluggish, heavy.

In the Industrial Revolution, Eenfeldt suggests, “the luxury of kings becomes everyday food.” In the eighteenth century, Swedes ate about a quarter pound of pure sugar per year. In 1850, that increased to nearly 9 pounds, and today 99 pounds! “Pure sugar that was a rare luxury commodity during the Middle Ages has since become cheaper and more commonplace. We can attribute that to the Industrial Revolution and its factories.”

Albert Schweitzer arrived in West Africa in April 1913. On average he saw thirty to forty people a day, most suffering from infections such as malaria. It took forty-one years before he saw an African patient with appendicitis—a regular occurrence in modern emergency rooms. Neither did he see cancer until the latter part of his time in Africa, when he treated an increasing number of cancer patients. Schweitzer suspected a connection as local people started living like their white visitors.

Weston A. Price, an American dentist, and his wife visited primitive populations around the world in the 1920s and 30s. They visited Australian aborigines, Polynesians, Eskimos, South and North American Indians, isolated villages in the Swiss mountains, and African tribes. The photos Price took are most revealing. The primitive populations had no dentists, no toothpaste or modern toothbrushes. “Despite this,” Eenfeldt observes, “they stood there smiling with bright white teeth that would make anyone in Hollywood jealous.” Price also sought out subsets of people living close to Western civilizations. Their photos were the complete opposite—broken teeth and terrible cavities. Eenfeldt’s conclusion: “If sugar and white flour can make your teeth rot, in what other ways can they harm the rest of your body?”

Thomas Latimer Cleave, born in 1906, became a doctor. He was hired by the British Navy, where he got to see diseases that occurred among different populations. Adding to his own observations, Cleave began asking other doctors for their experience with diseases. As Eenfeldt explains,

Cleave noted a long list of new diseases that had suddenly become prevalent around the world in a few decades. That could not be natural. He could only make one conclusion. Our bodies were not ill-designed, just improperly used. The diseases include obesity, diabetes, heart disease, gallstones, cavities, constipation, ulcers, and appendicitis.

He started publishing texts about his theory and summarized his research in The Saccharine Disease in 1974. Sugar and white flour were regarded as the cause behind all of the Western diseases.

Cleave was convinced that the issue was the purification and concentration of carbohydrates. It tricks us into eating more and can result in obesity over time. You don’t gain weight by being gluttonous or lazy. He noted how no wild animals become obese, regardless of the amount of food they have access to. Not when they keep their natural diet. The same should go for humans, but the problems arose with the new food.

Sir Richard Doll, one of the doctors who linked smoking with lung cancer, wrote one of the forewords for Cleave’s early books. Denis Burkitt, another renowned doctor, wrote the forward to The Saccharine Disease. Others agreed with Cleave. According to Eenfeldt, “At one point, things looked promising for Cleave’s theory. It could have changed the world.”

Another theory

What happened next, says Eenfeldt is a story “reminiscent of both a thriller and a catastrophe movie.” Eenfeldt paints the picture of the critical day:

“Sorry, it’s true. Cholesterol really is a killer. No fatty milk, No butter. No fatty meat.. .”

It is March 26, 1984, and the Americans were to be scared. They were to be scared of fat. The headline and the first sentence in a foreboding TIME magazine article leave no doubts. Neither does the cover (shown above), which featured a sad breakfast plate. The egg eyes and bacon mouth illustrate the sadness. The headlines say the rest: CHOLESTEROL—AND NOW THE BAD NEWS…

Strangely enough, the media was reporting on a pharmaceutical research report. A cholesterol-lowering drug had been found to reduce the risk of having a heart attack. After a couple of failed attempts, it was the first study to put forth a theory about the danger of fat. It was a popular theory on which many politicians, scientists, and lobbyists had bet their careers. Finally they had their chance. But were they right?

If one pill results in fewer heart attacks for risk patients, does that prove than lean cuisine can make Americans healthier?

The answer is, of course, no. The fear mongering was a long shot. No one could know what would happen. The politicians and scientists who supported the theory were probably under the impression that they were doing some good and that the end justified the means. With their conviction that fat was dangerous, they relaxed the requirement for scientific proof. When we look back, the conclusion is evident. The emperor had no clothes that day. Conviction cannot replace proof.

Rewind to 1958. Ancel Keys—the scientist on the 1961 TIME cover—thought he had the answer to heart disease in cholesterol. It needed to disappear.

Keys was a driven researcher who, according to Eenfeldt, sought the public spotlight. During World War II he designed the army’s rations, called K-rations. By the end of the war he had completed a study on starvation, using 36 conscientious objectors, who were starved during six months of meticulous monitoring. This research raised ethical questions about Keys’ research. But he persisted in his quest for recognition and it was his research on heart disease that earned him the name “Mr. Cholesterol” and the cover photo on TIME.

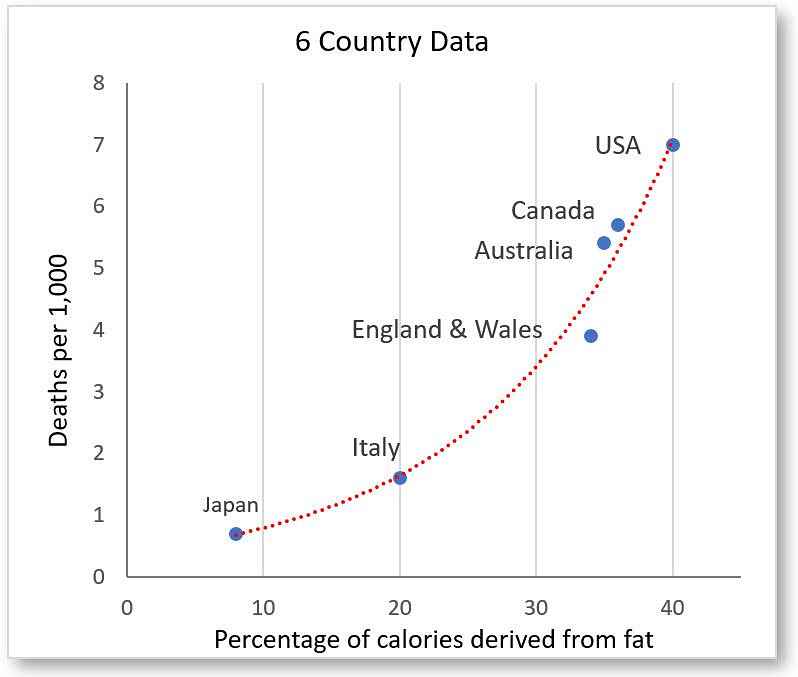

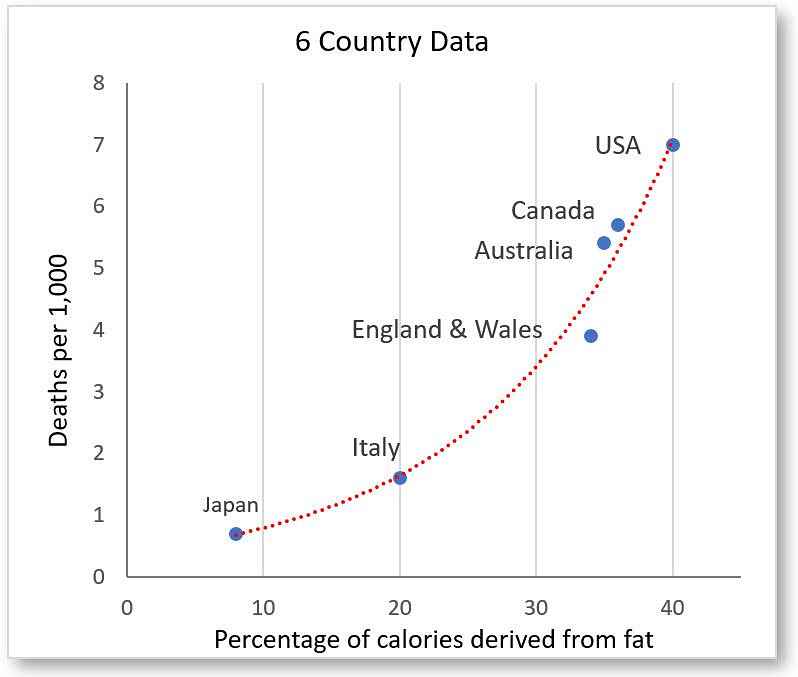

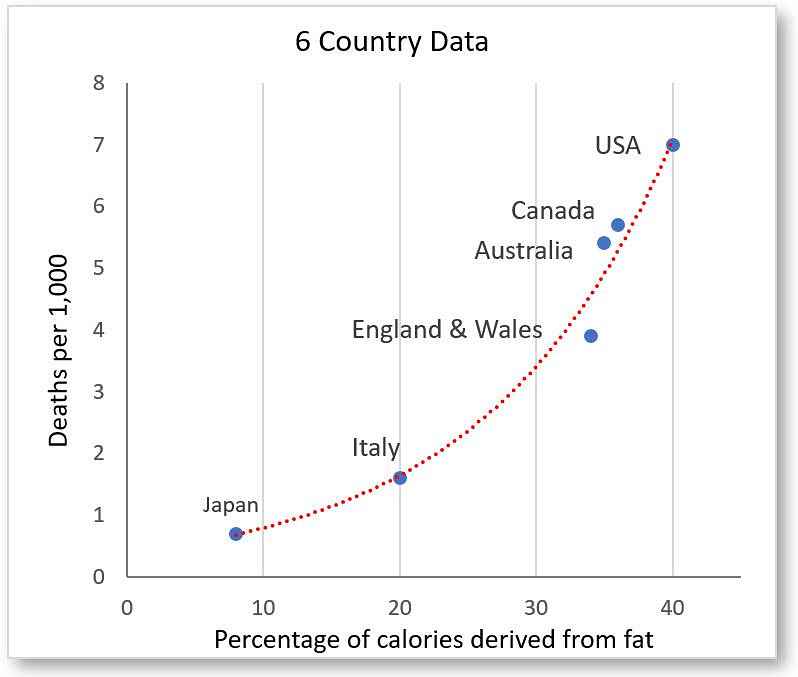

Eenfeldt goes into considerable detail about Keys’ research. During the 1950s Keys and his wife, a biochemist, traveled the world to gather data on the potential correlation between fat, cholesterol, and heart disease. Figure 1 shows what appears to show a solid correlation between deaths from heart disease and percentage of calories derived from fat in the populations of the six countries.

Figure 1

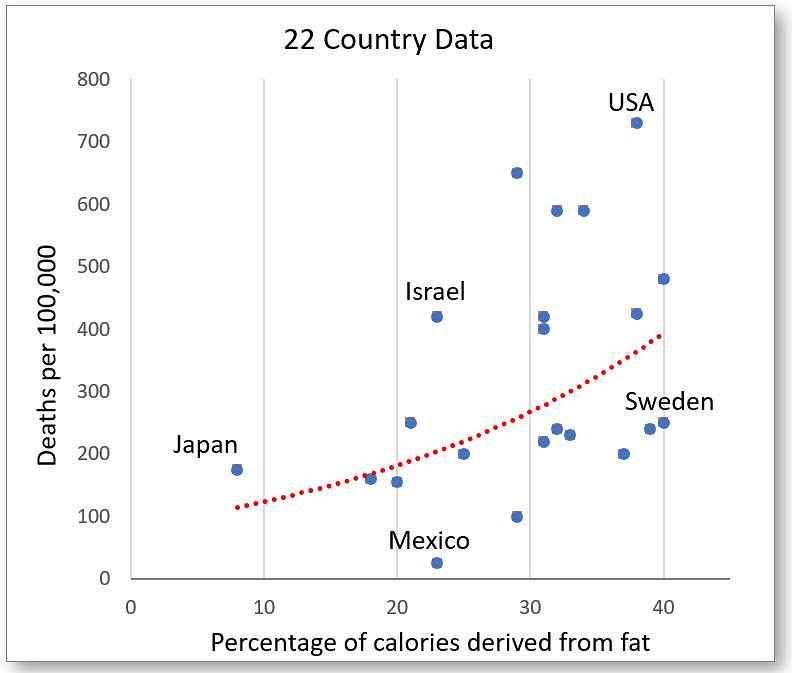

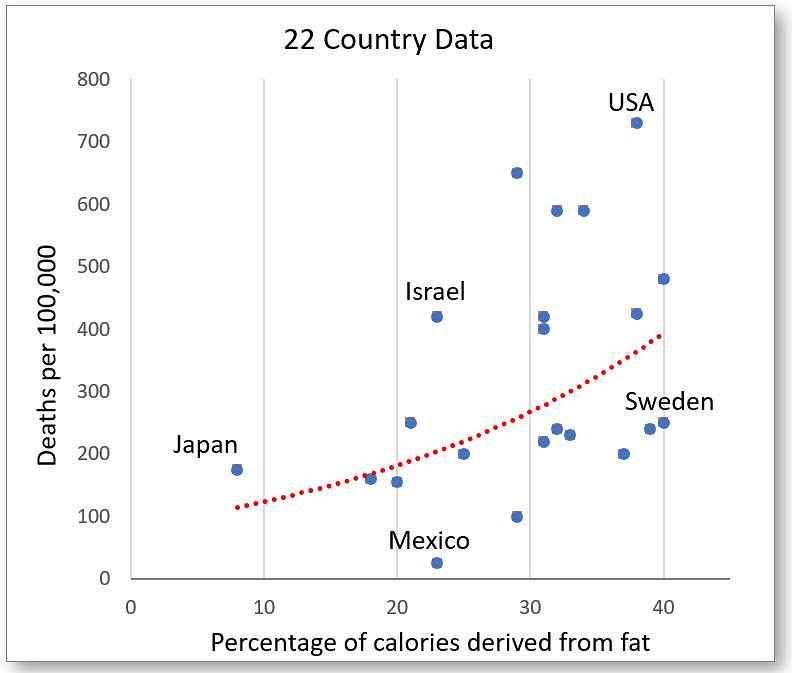

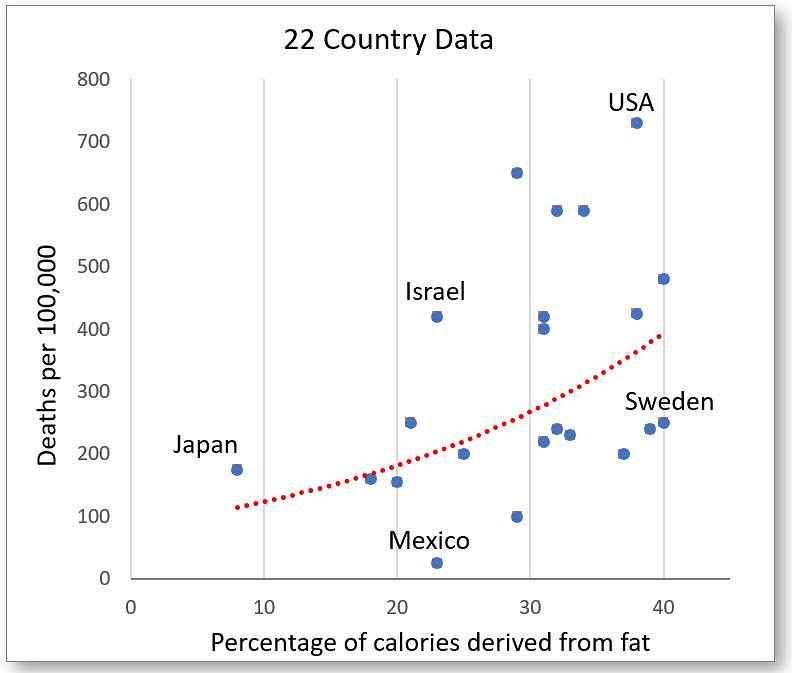

However, some years later, a skeptical colleague dug deeper into data from broader studies. Figure 2 shows how the larger data set of twenty-two countries was far less conclusive.

Figure 2

The correlation here is much weaker, hardly the near-perfect correlation of the 6-country data. As Eenfeldt states, “Keys had managed to choose exactly those countries that illustrated maximum correlation. . . . To simply pick out the statistics that fit one’s theory is a fatal scientific error. But the alleged forgery was not particularly well known, and Keys was not backing down.”

In 1958 Keys conducted a Seven Countries study that could have become the main pillar of the fear of fat. However, the data from the seven countries (Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Holland, Finland, Japan and the US), which was collected over an extended period, did not show a remote correlation between fat and heart disease. In Greece (the island of Crete), people ate a lot of fat, but had the fewest cases of heart disease. So, Keys changed his approach and focused on saturated fat. In itself, looking at another factor is the proper scientific approach, as long as it leads to a better explanation.

After a technical explanation of why saturated fat cannot be the culprit, Eenfeldt suggests how causality can be claimed where in fact there is no basis. To illustrate how far off the mark this can be, he uses a chart that seems to correlate municipal taxation with deaths caused by heart attacks—heart attacks increasing with higher tax rates. The chart would suggest that lowering taxes even more could eliminate heart attack deaths. Obviously, there has to be another explanation.

Or take the suggestion of a link between ice cream and drownings in Sweden. There may be a statistical correlation, but not a causal relationship. In fact, both ice cream consumption and drownings go up in the summer, but the real link—warm weather—produces the conditions to see an increase in both factors. In reality, the warm weather is not the cause of either ice cream consumption or drowning, but increases the opportunity for the real causes to produce their outcome.

Scientific method relies on well-crafted studies that are large enough to establish a control group and one or more test groups so that variables can be properly assessed. Eenfeldt calls these “intervention” studies. Good research further requires repetition of studies to see whether the reported conclusions are repeatable and the underlying assumptions valid. Only after extensive, multiple studies can a true consensus be reached, and if significant enough, a new paradigm (theory) adopted.

While the two theories—the ill effects of starch and sugar versus the fear of fat—were mirror images of each other, and despite problems with the latter theory, it moved into public acceptance. The theory of sugar and starch as the root of modern disease fell on hard times. Despite compelling data, it lacked advocates with the persuasive personality of Keys and for other reasons never reached the arena of public opinion. This opened the door for the fear of fat to win the day. “The problem was essentially very simple,” says Eenfeldt. “If fat was dangerous, carbohydrates had to be healthy. Otherwise there would be nothing with which to replace the fat.” Even soda, with all of its sugar could be called “low” or “no fat” to make it sound like a healthy alternative.

Enter the political arena. A committee led by Senator George McGovern had been focusing on the issue of malnutrition, but paused to review the problem of over-nutrition. In July 1976, after two days of testimony by experts, they wrote the first edition of The Diet of the United States. “When it came to fat, they predominantly relied on the experts that were convinced of the dangerous nature of fat, and the recommendation was to reduce one’s fat consumption.”

The recommendations, however, were controversial. The committee later published an updated version with more relaxed phrasing, but a similar low-fat theme. “A low-fat diet gradually became the norm,” while the scientific world was still in deep disagreement.” In the 1980s a series of studies were conducted, but according to Eenfeldt, failed to provide solid evidence of the link between dietary fat and heart disease. A sixth study tipped the scales, providing statistically significant numbers, but that study was testing a medication to reduce high cholesterol levels. “The conclusion was that a low-fat diet would produce the same cholesterol-reducing results. That was something the study had not even tested, something that every similar study has failed to this day.” But there was inertia behind the idea that there must be a link, so the public was receptive.

The paradigm shift to low-fat came in 1984 during an official “consensus conference.” According to Eenfeldt, “The board was comprised of people who were already convinced. Dissidents did not affect the conclusion. There were ‘no doubts,’ they said, that a low-fat diet would protect Americans older than two years against heart disease. . . . Stubborn dissidents were ostracized. . . . Skeptics were not favored.” To get federal funding for research (in the U.S.) required sticking to research fitting the low-fat theory.

A number of early critics saw holes in the theory, but it was the global epidemic of diabetes and obesity since 1984 that could not be denied. “Obesity has taken over in the United States in an unprecedented way. Now the epidemic is spreading across the Western world and beyond.”

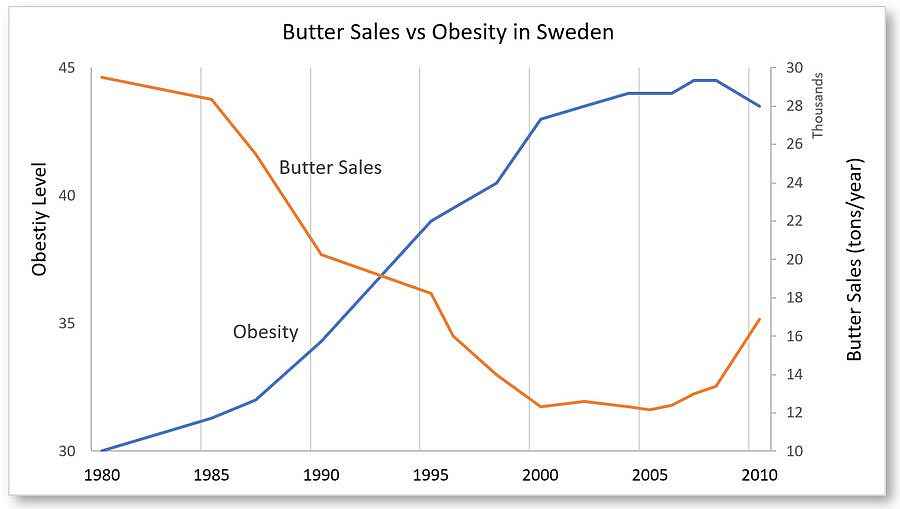

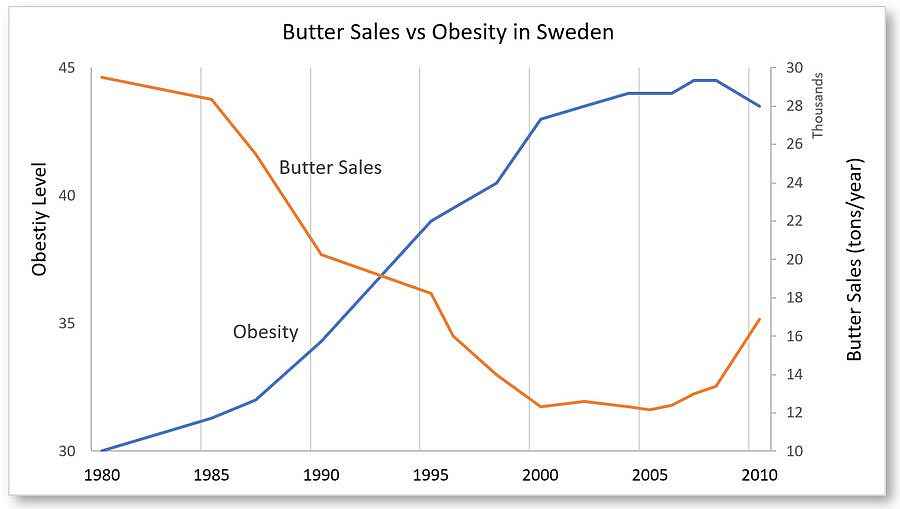

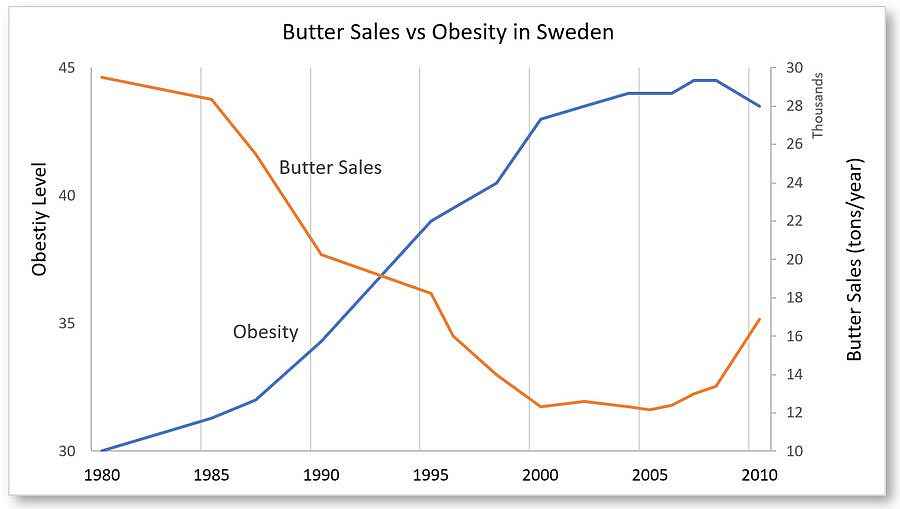

Eenfeldt then describes the research in Sweden, including his own, that began to take seriously the problems with the low-fat approach, which had become widely accepted there. In discussing the impact, he uses a chart that shows the mirror-image relation of butter consumption and obesity (Figure 3).

Figure 3

The adoption of low-fat diets (replaced by high carbs dominated by starch and sugar) in the 1980s, led to the steady rise in obesity, illustrated here by data from Sweden. That shift in diet caused butter sales to plummet as people reduced saturated fats (by substituting highly processed carbs and switching to other “healthier” fats). As awareness that the Low-Fat Revolution was producing disastrous results, diet in Sweden began to back away from the low-fat approach around 2005. Butter sales began going back up, while obesity leveled off and has now started to decline.

Using a single factor, like butter sales, is illuminating, but needs to be seen as one of many factors. After all, if that farmer from the south of Sweden simply slathered his buckwheat porridge in butter, he would not be turning it into health food! A similar mixed message was illustrated in a recent news story that linked a shortage of butter in France to growing world-wide demand for croissants. In other words, the chart will only work when it represents a transition from a low-fat to a low-carb diet, which may then lead to switching from butter substitutes to the real thing.

Lessons to Apply

So, what can we learn from the low-fat paradigm shift that brought such widespread unintended consequences that it is now being questioned?

Scientific method must be followed and allowed to run its course. That means multiple studies or experiments over a long enough period of time to establish correlations and corroborate results. A problem in the low-fat paradigm shift was lowering the bar on the quality and quantity of research.

Scientific method assumes the honest presentation and interpretation of data. Yet, it is so easy to manipulate these, intentionally or more subtly when the researcher is bent on proving a point. The Six-Country study of Keys versus the broader 22-Country data cited above illustrate this.

In subtle ways, the presentation of data can be influenced by the scale of a chart or the range of an axis to make a trend appear more or less dramatic than it may, in fact, be. I could take the same data and produce a chart that will make a trend look undeniable or insignificant, depending on how I configure the chart.

Arriving at consensus can become a huge political exercise, even among scientists supposedly using scientific method to find the best theory at a given time. With the high cost of research, the competition for research dollars (which may itself be biased toward a favored conclusion), and the potential battle of egos for recognition, there must be controls to remove bias in the process. The Low-Fat Revolution shows how this became a mix of biases or lack of scrutiny across science, government, and the media.

If the wrong conclusion is reached—as was the case with the Low-Fat Revolution—it will eventually be overturned as the puzzle pieces no longer fit, but with what damage to the population in the meantime? Just as worrisome, can a “correction” swing the pendulum too far in the opposite direction, leading to a new set of unintended consequences? That is why the patient achievement of consensus through rigorous research under the highest ethical standards and free from political agendas is so important.

Journalism and politics play important roles in the public acceptance of new approaches to problems. In the Low-Fat Revolution, both institutions failed.

Long before “fake news” came into vogue, it has been my observation that there has been a trend over decades for a weakening of reporting on science, technology, and social science research. Much of what is reported as news is not scientifically valid, relying on the reporting of poorly trained journalists or, worse, serving as a conduit for press releases passing as news.

When our local paper had a weekly health section, it was common to see articles proclaiming exciting new developments. Increasingly, they were a reporter’s recitation of a single study, without digging deeper to look for similar studies or—even better—summary studies that seek out and attempt to corroborate enough studies to disprove or validate a theory. Worse yet were “stories” that were clearly no more than passing on a news release from an advocacy group or researcher trying to gain attention. Journalists must be skeptics, particularly avoiding a single source as authoritative without looking at the broader context (surveying the literature, as one would do in a scholarly treatise).

Adding the influence of politics from the government sector (elected officials as well as bureaucracy) can create biases and agendas that serve partisan interests more than the public good, potentially ignoring the time required for effective research and consensus-building, especially when science is involved.

The mix of media and politics—and the false urgency of the 24-hour news cycle—only exacerbate these problem.

The failure of the Low-Fat Revolution provides an example of how a paradigm shift can be premature or misguided—with potentially disastrous results—and the complex mix of players required to get it right.

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: October 304, 2017 Accessed 5,639 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: Planning / Topics: Government • History • Media • Planning • Research Methodology • Science & Technology • Statistics

A Paradigm Collapses

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: October 304, 2017

Lessons from three decades of the Low-Fat Revolution…

When I had my annual physical recently, my doctor once again extolled the virtues of a low-carb diet, which he has been promoting for some time now. I had followed some of the advice and lost weight, but still had a way to go. This time, I read his handout again and decided to explore the references. The first one I looked at was Low Carb, High Fat by Andreas Eenfeldt, MD, a Swedish doctor and researcher, whose work (and movement) can also be found on www.dietdoctor.com.

The story as told by Dr. Eenfeldt not only confirmed what my own doctor had been saying from a health standpoint. But it also told another story that revealed how the major paradigm shift to the “fear of fat” occurred in 1984 in the U.S. and spread globally under the new mantra of “Low-Fat.” There are lessons here for many other areas of life. What we find is the interplay of competing ideas where the “winner” is determined not by careful and long-term application of scientific method, but through the power of ego, politics, media, and the misuse of statistics to arrive at “consensus.” That is what we will look at here, using the Low-Fat Revolution as a case study.

Since 1984 when the “fear of fat” was widely proclaimed in the United States, we have come to face a global health crisis, with levels of obesity and diabetes skyrocketing. Type 2 diabetes has increased from 30 million worldwide in 1985 to 415 million in 2015, a nearly thirteen-fold increase in the thirty years since “Low-Fat” became the watchword of good health.

At the same time, obesity rates have steadily climbed. (In a 39-minute video from a seminar he gave, Dr. Eenfeldt uses a series of U.S. maps that show how dramatically obesity has increased since the Low-Fat paradigm shift).

I was struck that such a powerful movement could head us so dramatically in the wrong direction. Eenfeldt himself admits to being convinced of the low-fat paradigm early on, though he came to see its failure and worked to correct it.

Puzzles and Paradigm Shifts

TIME magazine covers tell the story of the “fear of fat” paradigm shift in three quick snapshots. A driving force leading to the Low-Fat Revolution in 1984 was the work of Ancel Keys (left, from a 1961 cover), who claimed that saturated fats in the diet clogged arteries and caused heart disease. While the research led to a drug to lower cholesterol levels, a 1984 cover (center) touted what was then the beginning of public awareness of the benefits of the low-fat approach to nutrition, assumed to produce similar results. By 2014, the “Eat Butter” cover (right) appeared, with the headline “Scientists labeled fat the enemy. Why they were wrong.”

That’s a startling reversal in a very short time. The June 2014 Health Impact News used the 1961 and 2014 covers to illustrate “Time Magazine: We Were Wrong About Saturated Fats,” adding “But don’t expect more mainstream media to follow this repentance on saturated fats.” Indeed, even the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, while backing off from the strong low-fat dictum of earlier guidelines, still shows the considerable influence of the Low-Fat approach touted for much of the past three decades. But, back to the story of the ascendancy and subsequent failure of the Low-Fat Revolution.

Dr. Eenfeldt’s overall assessment is that the adoption of the low-fat approach was a paradigm shift that proved to be wrong, so the paradigm must shift again. This time, he argues, it must shift to a low-carb approach derived from the competing theory of the dangers of starch and sugar. As he explains, these shifts take time and can leave a battlefield strewn with casualties.

In 1962, when Thomas Kuhn wrote the book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, he became the most influential scientific theorist in modern history. He presented a new idea about how scientific progress is made: usually slowly but surely, one piece of the puzzle at a time. But sometimes, the opposite is true. More and more pieces no longer fit into the puzzle, no matter how hard you try. Eventually the contradictions became too many to ignore and explain away. A revolution is inevitable.

The revolution is a paradigm shift. Scientists always interpret their research from their current perception of the world, their paradigm. In revolutions, the old world view is thrown out. A new and better perspective takes over. A new way of piecing together the puzzle. A clearer picture, in which all the pieces fit together. . . .

World view changes in science happen now and then. It is not a strange thing. On the contrary, they are sometimes inevitable. They can happen violently. There could arise an intellectual battle between early adopters and those who stick to the old truth. If the new world view is sufficiently better, it eventually becomes dogma. But it takes years or sometimes decades before the switch is complete. . . .

Not everyone is keen on changing his or her world view, despite how clear the evidence is. They say that a new scientific theory breaks through not by proving dissenters wrong and making them see the light, but because they eventually die out. A new generation who knows the new theory takes over. . . .

If can be difficult to admit “I was wrong” about little things. When it comes to something on which you have built your whole career, that can be difficult to admit even to yourself. Few can handle it. [Eenfeldt, pp 67-70]

In retrospect, the case of the low-fat theory was developed as puzzle pieces appeared to come together, but then as research continued (applying proper scientific method), the pieces began to come apart nearly as quickly, with the new pieces revealing a different picture.

Getting to now: from Hunter-Gatherers to the Fear of Fat

Before getting to the battle of competing theories, it may be helpful to understand Eenfeldt’s portrayal of the relationship between humans and food. In the following description the time-frame, in parentheses, compresses five-million years of human history into a single year:

Hunter-gatherers (364 days) – “We consumed food readily available in nature. . . We received plenty of protein and energy from fat and moderate amounts of indigestible carbohydrates.” Then, in more recent history, three important transformations occurred:

- Agriculture (the last day of the year, New Year’s Eve) – “The agricultural revolution changed everything. It started nine thousand years ago, in today’s Iraq. . . . It arrived in the Nordics some four thousand years ago. . . . The agricultural food was different from what we had eaten before: bread, rice, potatoes, pasta, and other farmed products that mostly consist of starch . . . which is broken down into pure glucose in your stomach.

- Industrial Revolution and the rise of “western food” (15 minutes before midnight on New Year’s Eve) – “The industrial revolution came with factories that produced new types of food. . . .The new white flour could be stored for long periods of time without attracting vermin due to the low nutritional value, since they cannot subsist on pure starch. That meant the flour could be shipped around the world as a trade commodity. . . . The industrial revolution gave us an additional commodity that could be shipped across the world . . . sugar has even more detrimental health effects than starch.

- The Fear of Fat (as the ball drops for the countdown to Midnight) – “The fear of fat and cholesterol exacerbated the changes that had taken place before. This fear resulted in many people eating more of the new food and a slowly emerging endemic disease.”

Eenfeldt goes on to describe what happens when you eat the new food—easily digestible carbohydrates. Starch and sugar quickly produce glucose in the blood, which raises the level of insulin, the body’s fat-storing hormone. Fat does not produce fat in the body, starch and simple carbohydrates do.

Looking for the culprit – heart disease, obesity, diabetes and/or diet

Two competing views of food and its impact on health emerged prior to the TIME magazine cover in 1984. According to researchers like Dr. Eenfeldt, the wrong view won the day.

The trouble with modern food.

You may be thinking, as I did, didn’t people survive quite well in the transition to agriculture? After all, ancient texts are full of examples of people eating grain and bread made from flour or meal ground from various grains. While there are differences between “ancient grains”—which are now touted as healthy—and modern highly refined wheat flour, the agricultural revolution did produce measurable individual and social changes from the very beginning. (See the 2013 paper from the University of Nebraska, “Human Health and the Neolithic Revolution” for an overview of numerous studies).

Seeing the impact of the first transformation—agricultural—the Swedish botanist and physician Carl Linnaeus wrote in his 1751 book Skånska Resa:

Diet has a great effect on the inhabitants of a country. A Laplander, or Saami [denomination of someone from the north of Sweden] lives on meat, fish, and birds, and is small, slim, light, nimble; but a farmer in the south of Sweden, in the plains of Skåne, who eats a lot of buckwheat porridge, and whose food consists chiefly of vegetabilibus farinaceis (vegetable flour dishes), grows big, coarse, stout, strong, sluggish, heavy.

In the Industrial Revolution, Eenfeldt suggests, “the luxury of kings becomes everyday food.” In the eighteenth century, Swedes ate about a quarter pound of pure sugar per year. In 1850, that increased to nearly 9 pounds, and today 99 pounds! “Pure sugar that was a rare luxury commodity during the Middle Ages has since become cheaper and more commonplace. We can attribute that to the Industrial Revolution and its factories.”

Albert Schweitzer arrived in West Africa in April 1913. On average he saw thirty to forty people a day, most suffering from infections such as malaria. It took forty-one years before he saw an African patient with appendicitis—a regular occurrence in modern emergency rooms. Neither did he see cancer until the latter part of his time in Africa, when he treated an increasing number of cancer patients. Schweitzer suspected a connection as local people started living like their white visitors.

Weston A. Price, an American dentist, and his wife visited primitive populations around the world in the 1920s and 30s. They visited Australian aborigines, Polynesians, Eskimos, South and North American Indians, isolated villages in the Swiss mountains, and African tribes. The photos Price took are most revealing. The primitive populations had no dentists, no toothpaste or modern toothbrushes. “Despite this,” Eenfeldt observes, “they stood there smiling with bright white teeth that would make anyone in Hollywood jealous.” Price also sought out subsets of people living close to Western civilizations. Their photos were the complete opposite—broken teeth and terrible cavities. Eenfeldt’s conclusion: “If sugar and white flour can make your teeth rot, in what other ways can they harm the rest of your body?”

Thomas Latimer Cleave, born in 1906, became a doctor. He was hired by the British Navy, where he got to see diseases that occurred among different populations. Adding to his own observations, Cleave began asking other doctors for their experience with diseases. As Eenfeldt explains,

Cleave noted a long list of new diseases that had suddenly become prevalent around the world in a few decades. That could not be natural. He could only make one conclusion. Our bodies were not ill-designed, just improperly used. The diseases include obesity, diabetes, heart disease, gallstones, cavities, constipation, ulcers, and appendicitis.

He started publishing texts about his theory and summarized his research in The Saccharine Disease in 1974. Sugar and white flour were regarded as the cause behind all of the Western diseases.

Cleave was convinced that the issue was the purification and concentration of carbohydrates. It tricks us into eating more and can result in obesity over time. You don’t gain weight by being gluttonous or lazy. He noted how no wild animals become obese, regardless of the amount of food they have access to. Not when they keep their natural diet. The same should go for humans, but the problems arose with the new food.

Sir Richard Doll, one of the doctors who linked smoking with lung cancer, wrote one of the forewords for Cleave’s early books. Denis Burkitt, another renowned doctor, wrote the forward to The Saccharine Disease. Others agreed with Cleave. According to Eenfeldt, “At one point, things looked promising for Cleave’s theory. It could have changed the world.”

Another theory

What happened next, says Eenfeldt is a story “reminiscent of both a thriller and a catastrophe movie.” Eenfeldt paints the picture of the critical day:

“Sorry, it’s true. Cholesterol really is a killer. No fatty milk, No butter. No fatty meat.. .”

It is March 26, 1984, and the Americans were to be scared. They were to be scared of fat. The headline and the first sentence in a foreboding TIME magazine article leave no doubts. Neither does the cover (shown above), which featured a sad breakfast plate. The egg eyes and bacon mouth illustrate the sadness. The headlines say the rest: CHOLESTEROL—AND NOW THE BAD NEWS…

Strangely enough, the media was reporting on a pharmaceutical research report. A cholesterol-lowering drug had been found to reduce the risk of having a heart attack. After a couple of failed attempts, it was the first study to put forth a theory about the danger of fat. It was a popular theory on which many politicians, scientists, and lobbyists had bet their careers. Finally they had their chance. But were they right?

If one pill results in fewer heart attacks for risk patients, does that prove than lean cuisine can make Americans healthier?

The answer is, of course, no. The fear mongering was a long shot. No one could know what would happen. The politicians and scientists who supported the theory were probably under the impression that they were doing some good and that the end justified the means. With their conviction that fat was dangerous, they relaxed the requirement for scientific proof. When we look back, the conclusion is evident. The emperor had no clothes that day. Conviction cannot replace proof.

Rewind to 1958. Ancel Keys—the scientist on the 1961 TIME cover—thought he had the answer to heart disease in cholesterol. It needed to disappear.

Keys was a driven researcher who, according to Eenfeldt, sought the public spotlight. During World War II he designed the army’s rations, called K-rations. By the end of the war he had completed a study on starvation, using 36 conscientious objectors, who were starved during six months of meticulous monitoring. This research raised ethical questions about Keys’ research. But he persisted in his quest for recognition and it was his research on heart disease that earned him the name “Mr. Cholesterol” and the cover photo on TIME.

Eenfeldt goes into considerable detail about Keys’ research. During the 1950s Keys and his wife, a biochemist, traveled the world to gather data on the potential correlation between fat, cholesterol, and heart disease. Figure 1 shows what appears to show a solid correlation between deaths from heart disease and percentage of calories derived from fat in the populations of the six countries.

Figure 1

However, some years later, a skeptical colleague dug deeper into data from broader studies. Figure 2 shows how the larger data set of twenty-two countries was far less conclusive.

Figure 2

The correlation here is much weaker, hardly the near-perfect correlation of the 6-country data. As Eenfeldt states, “Keys had managed to choose exactly those countries that illustrated maximum correlation. . . . To simply pick out the statistics that fit one’s theory is a fatal scientific error. But the alleged forgery was not particularly well known, and Keys was not backing down.”

In 1958 Keys conducted a Seven Countries study that could have become the main pillar of the fear of fat. However, the data from the seven countries (Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Holland, Finland, Japan and the US), which was collected over an extended period, did not show a remote correlation between fat and heart disease. In Greece (the island of Crete), people ate a lot of fat, but had the fewest cases of heart disease. So, Keys changed his approach and focused on saturated fat. In itself, looking at another factor is the proper scientific approach, as long as it leads to a better explanation.

After a technical explanation of why saturated fat cannot be the culprit, Eenfeldt suggests how causality can be claimed where in fact there is no basis. To illustrate how far off the mark this can be, he uses a chart that seems to correlate municipal taxation with deaths caused by heart attacks—heart attacks increasing with higher tax rates. The chart would suggest that lowering taxes even more could eliminate heart attack deaths. Obviously, there has to be another explanation.

Or take the suggestion of a link between ice cream and drownings in Sweden. There may be a statistical correlation, but not a causal relationship. In fact, both ice cream consumption and drownings go up in the summer, but the real link—warm weather—produces the conditions to see an increase in both factors. In reality, the warm weather is not the cause of either ice cream consumption or drowning, but increases the opportunity for the real causes to produce their outcome.

Scientific method relies on well-crafted studies that are large enough to establish a control group and one or more test groups so that variables can be properly assessed. Eenfeldt calls these “intervention” studies. Good research further requires repetition of studies to see whether the reported conclusions are repeatable and the underlying assumptions valid. Only after extensive, multiple studies can a true consensus be reached, and if significant enough, a new paradigm (theory) adopted.

While the two theories—the ill effects of starch and sugar versus the fear of fat—were mirror images of each other, and despite problems with the latter theory, it moved into public acceptance. The theory of sugar and starch as the root of modern disease fell on hard times. Despite compelling data, it lacked advocates with the persuasive personality of Keys and for other reasons never reached the arena of public opinion. This opened the door for the fear of fat to win the day. “The problem was essentially very simple,” says Eenfeldt. “If fat was dangerous, carbohydrates had to be healthy. Otherwise there would be nothing with which to replace the fat.” Even soda, with all of its sugar could be called “low” or “no fat” to make it sound like a healthy alternative.

Enter the political arena. A committee led by Senator George McGovern had been focusing on the issue of malnutrition, but paused to review the problem of over-nutrition. In July 1976, after two days of testimony by experts, they wrote the first edition of The Diet of the United States. “When it came to fat, they predominantly relied on the experts that were convinced of the dangerous nature of fat, and the recommendation was to reduce one’s fat consumption.”

The recommendations, however, were controversial. The committee later published an updated version with more relaxed phrasing, but a similar low-fat theme. “A low-fat diet gradually became the norm,” while the scientific world was still in deep disagreement.” In the 1980s a series of studies were conducted, but according to Eenfeldt, failed to provide solid evidence of the link between dietary fat and heart disease. A sixth study tipped the scales, providing statistically significant numbers, but that study was testing a medication to reduce high cholesterol levels. “The conclusion was that a low-fat diet would produce the same cholesterol-reducing results. That was something the study had not even tested, something that every similar study has failed to this day.” But there was inertia behind the idea that there must be a link, so the public was receptive.

The paradigm shift to low-fat came in 1984 during an official “consensus conference.” According to Eenfeldt, “The board was comprised of people who were already convinced. Dissidents did not affect the conclusion. There were ‘no doubts,’ they said, that a low-fat diet would protect Americans older than two years against heart disease. . . . Stubborn dissidents were ostracized. . . . Skeptics were not favored.” To get federal funding for research (in the U.S.) required sticking to research fitting the low-fat theory.

A number of early critics saw holes in the theory, but it was the global epidemic of diabetes and obesity since 1984 that could not be denied. “Obesity has taken over in the United States in an unprecedented way. Now the epidemic is spreading across the Western world and beyond.”

Eenfeldt then describes the research in Sweden, including his own, that began to take seriously the problems with the low-fat approach, which had become widely accepted there. In discussing the impact, he uses a chart that shows the mirror-image relation of butter consumption and obesity (Figure 3).

Figure 3

The adoption of low-fat diets (replaced by high carbs dominated by starch and sugar) in the 1980s, led to the steady rise in obesity, illustrated here by data from Sweden. That shift in diet caused butter sales to plummet as people reduced saturated fats (by substituting highly processed carbs and switching to other “healthier” fats). As awareness that the Low-Fat Revolution was producing disastrous results, diet in Sweden began to back away from the low-fat approach around 2005. Butter sales began going back up, while obesity leveled off and has now started to decline.

Using a single factor, like butter sales, is illuminating, but needs to be seen as one of many factors. After all, if that farmer from the south of Sweden simply slathered his buckwheat porridge in butter, he would not be turning it into health food! A similar mixed message was illustrated in a recent news story that linked a shortage of butter in France to growing world-wide demand for croissants. In other words, the chart will only work when it represents a transition from a low-fat to a low-carb diet, which may then lead to switching from butter substitutes to the real thing.

Lessons to Apply

So, what can we learn from the low-fat paradigm shift that brought such widespread unintended consequences that it is now being questioned?

Scientific method must be followed and allowed to run its course. That means multiple studies or experiments over a long enough period of time to establish correlations and corroborate results. A problem in the low-fat paradigm shift was lowering the bar on the quality and quantity of research.

Scientific method assumes the honest presentation and interpretation of data. Yet, it is so easy to manipulate these, intentionally or more subtly when the researcher is bent on proving a point. The Six-Country study of Keys versus the broader 22-Country data cited above illustrate this.

In subtle ways, the presentation of data can be influenced by the scale of a chart or the range of an axis to make a trend appear more or less dramatic than it may, in fact, be. I could take the same data and produce a chart that will make a trend look undeniable or insignificant, depending on how I configure the chart.

Arriving at consensus can become a huge political exercise, even among scientists supposedly using scientific method to find the best theory at a given time. With the high cost of research, the competition for research dollars (which may itself be biased toward a favored conclusion), and the potential battle of egos for recognition, there must be controls to remove bias in the process. The Low-Fat Revolution shows how this became a mix of biases or lack of scrutiny across science, government, and the media.

If the wrong conclusion is reached—as was the case with the Low-Fat Revolution—it will eventually be overturned as the puzzle pieces no longer fit, but with what damage to the population in the meantime? Just as worrisome, can a “correction” swing the pendulum too far in the opposite direction, leading to a new set of unintended consequences? That is why the patient achievement of consensus through rigorous research under the highest ethical standards and free from political agendas is so important.

Journalism and politics play important roles in the public acceptance of new approaches to problems. In the Low-Fat Revolution, both institutions failed.

Long before “fake news” came into vogue, it has been my observation that there has been a trend over decades for a weakening of reporting on science, technology, and social science research. Much of what is reported as news is not scientifically valid, relying on the reporting of poorly trained journalists or, worse, serving as a conduit for press releases passing as news.

When our local paper had a weekly health section, it was common to see articles proclaiming exciting new developments. Increasingly, they were a reporter’s recitation of a single study, without digging deeper to look for similar studies or—even better—summary studies that seek out and attempt to corroborate enough studies to disprove or validate a theory. Worse yet were “stories” that were clearly no more than passing on a news release from an advocacy group or researcher trying to gain attention. Journalists must be skeptics, particularly avoiding a single source as authoritative without looking at the broader context (surveying the literature, as one would do in a scholarly treatise).

Adding the influence of politics from the government sector (elected officials as well as bureaucracy) can create biases and agendas that serve partisan interests more than the public good, potentially ignoring the time required for effective research and consensus-building, especially when science is involved.

The mix of media and politics—and the false urgency of the 24-hour news cycle—only exacerbate these problem.

The failure of the Low-Fat Revolution provides an example of how a paradigm shift can be premature or misguided—with potentially disastrous results—and the complex mix of players required to get it right.

Search all articles by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...

Building article list (this could take a few moments) ...Stu Johnson is owner of Stuart Johnson & Associates, a communications consultancy in Wheaton, Illinois focused on "making information make sense."

• E-mail the author (moc.setaicossajs@uts*)* For web-based email, you may need to copy and paste the address yourself.

Posted: October 304, 2017 Accessed 5,640 times

![]() Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

Go to the list of most recent InfoMatters Blogs

![]() Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Search InfoMatters (You can expand the search to the entire site)

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...

Loading requested view (this could take a few moments)...InfoMatters

Category: Planning / Topics: Government • History • Media • Planning • Research Methodology • Science & Technology • Statistics

A Paradigm Collapses

by Stu Johnson

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...

Building article list (this could take a few moments)...Posted: October 304, 2017

Lessons from three decades of the Low-Fat Revolution…

When I had my annual physical recently, my doctor once again extolled the virtues of a low-carb diet, which he has been promoting for some time now. I had followed some of the advice and lost weight, but still had a way to go. This time, I read his handout again and decided to explore the references. The first one I looked at was Low Carb, High Fat by Andreas Eenfeldt, MD, a Swedish doctor and researcher, whose work (and movement) can also be found on www.dietdoctor.com.

The story as told by Dr. Eenfeldt not only confirmed what my own doctor had been saying from a health standpoint. But it also told another story that revealed how the major paradigm shift to the “fear of fat” occurred in 1984 in the U.S. and spread globally under the new mantra of “Low-Fat.” There are lessons here for many other areas of life. What we find is the interplay of competing ideas where the “winner” is determined not by careful and long-term application of scientific method, but through the power of ego, politics, media, and the misuse of statistics to arrive at “consensus.” That is what we will look at here, using the Low-Fat Revolution as a case study.

Since 1984 when the “fear of fat” was widely proclaimed in the United States, we have come to face a global health crisis, with levels of obesity and diabetes skyrocketing. Type 2 diabetes has increased from 30 million worldwide in 1985 to 415 million in 2015, a nearly thirteen-fold increase in the thirty years since “Low-Fat” became the watchword of good health.

At the same time, obesity rates have steadily climbed. (In a 39-minute video from a seminar he gave, Dr. Eenfeldt uses a series of U.S. maps that show how dramatically obesity has increased since the Low-Fat paradigm shift).

I was struck that such a powerful movement could head us so dramatically in the wrong direction. Eenfeldt himself admits to being convinced of the low-fat paradigm early on, though he came to see its failure and worked to correct it.

Puzzles and Paradigm Shifts

TIME magazine covers tell the story of the “fear of fat” paradigm shift in three quick snapshots. A driving force leading to the Low-Fat Revolution in 1984 was the work of Ancel Keys (left, from a 1961 cover), who claimed that saturated fats in the diet clogged arteries and caused heart disease. While the research led to a drug to lower cholesterol levels, a 1984 cover (center) touted what was then the beginning of public awareness of the benefits of the low-fat approach to nutrition, assumed to produce similar results. By 2014, the “Eat Butter” cover (right) appeared, with the headline “Scientists labeled fat the enemy. Why they were wrong.”

That’s a startling reversal in a very short time. The June 2014 Health Impact News used the 1961 and 2014 covers to illustrate “Time Magazine: We Were Wrong About Saturated Fats,” adding “But don’t expect more mainstream media to follow this repentance on saturated fats.” Indeed, even the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, while backing off from the strong low-fat dictum of earlier guidelines, still shows the considerable influence of the Low-Fat approach touted for much of the past three decades. But, back to the story of the ascendancy and subsequent failure of the Low-Fat Revolution.

Dr. Eenfeldt’s overall assessment is that the adoption of the low-fat approach was a paradigm shift that proved to be wrong, so the paradigm must shift again. This time, he argues, it must shift to a low-carb approach derived from the competing theory of the dangers of starch and sugar. As he explains, these shifts take time and can leave a battlefield strewn with casualties.

In 1962, when Thomas Kuhn wrote the book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, he became the most influential scientific theorist in modern history. He presented a new idea about how scientific progress is made: usually slowly but surely, one piece of the puzzle at a time. But sometimes, the opposite is true. More and more pieces no longer fit into the puzzle, no matter how hard you try. Eventually the contradictions became too many to ignore and explain away. A revolution is inevitable.

The revolution is a paradigm shift. Scientists always interpret their research from their current perception of the world, their paradigm. In revolutions, the old world view is thrown out. A new and better perspective takes over. A new way of piecing together the puzzle. A clearer picture, in which all the pieces fit together. . . .

World view changes in science happen now and then. It is not a strange thing. On the contrary, they are sometimes inevitable. They can happen violently. There could arise an intellectual battle between early adopters and those who stick to the old truth. If the new world view is sufficiently better, it eventually becomes dogma. But it takes years or sometimes decades before the switch is complete. . . .

Not everyone is keen on changing his or her world view, despite how clear the evidence is. They say that a new scientific theory breaks through not by proving dissenters wrong and making them see the light, but because they eventually die out. A new generation who knows the new theory takes over. . . .

If can be difficult to admit “I was wrong” about little things. When it comes to something on which you have built your whole career, that can be difficult to admit even to yourself. Few can handle it. [Eenfeldt, pp 67-70]

In retrospect, the case of the low-fat theory was developed as puzzle pieces appeared to come together, but then as research continued (applying proper scientific method), the pieces began to come apart nearly as quickly, with the new pieces revealing a different picture.

Getting to now: from Hunter-Gatherers to the Fear of Fat

Before getting to the battle of competing theories, it may be helpful to understand Eenfeldt’s portrayal of the relationship between humans and food. In the following description the time-frame, in parentheses, compresses five-million years of human history into a single year:

Hunter-gatherers (364 days) – “We consumed food readily available in nature. . . We received plenty of protein and energy from fat and moderate amounts of indigestible carbohydrates.” Then, in more recent history, three important transformations occurred:

- Agriculture (the last day of the year, New Year’s Eve) – “The agricultural revolution changed everything. It started nine thousand years ago, in today’s Iraq. . . . It arrived in the Nordics some four thousand years ago. . . . The agricultural food was different from what we had eaten before: bread, rice, potatoes, pasta, and other farmed products that mostly consist of starch . . . which is broken down into pure glucose in your stomach.

- Industrial Revolution and the rise of “western food” (15 minutes before midnight on New Year’s Eve) – “The industrial revolution came with factories that produced new types of food. . . .The new white flour could be stored for long periods of time without attracting vermin due to the low nutritional value, since they cannot subsist on pure starch. That meant the flour could be shipped around the world as a trade commodity. . . . The industrial revolution gave us an additional commodity that could be shipped across the world . . . sugar has even more detrimental health effects than starch.

- The Fear of Fat (as the ball drops for the countdown to Midnight) – “The fear of fat and cholesterol exacerbated the changes that had taken place before. This fear resulted in many people eating more of the new food and a slowly emerging endemic disease.”

Eenfeldt goes on to describe what happens when you eat the new food—easily digestible carbohydrates. Starch and sugar quickly produce glucose in the blood, which raises the level of insulin, the body’s fat-storing hormone. Fat does not produce fat in the body, starch and simple carbohydrates do.

Looking for the culprit – heart disease, obesity, diabetes and/or diet

Two competing views of food and its impact on health emerged prior to the TIME magazine cover in 1984. According to researchers like Dr. Eenfeldt, the wrong view won the day.

The trouble with modern food.

You may be thinking, as I did, didn’t people survive quite well in the transition to agriculture? After all, ancient texts are full of examples of people eating grain and bread made from flour or meal ground from various grains. While there are differences between “ancient grains”—which are now touted as healthy—and modern highly refined wheat flour, the agricultural revolution did produce measurable individual and social changes from the very beginning. (See the 2013 paper from the University of Nebraska, “Human Health and the Neolithic Revolution” for an overview of numerous studies).

Seeing the impact of the first transformation—agricultural—the Swedish botanist and physician Carl Linnaeus wrote in his 1751 book Skånska Resa:

Diet has a great effect on the inhabitants of a country. A Laplander, or Saami [denomination of someone from the north of Sweden] lives on meat, fish, and birds, and is small, slim, light, nimble; but a farmer in the south of Sweden, in the plains of Skåne, who eats a lot of buckwheat porridge, and whose food consists chiefly of vegetabilibus farinaceis (vegetable flour dishes), grows big, coarse, stout, strong, sluggish, heavy.

In the Industrial Revolution, Eenfeldt suggests, “the luxury of kings becomes everyday food.” In the eighteenth century, Swedes ate about a quarter pound of pure sugar per year. In 1850, that increased to nearly 9 pounds, and today 99 pounds! “Pure sugar that was a rare luxury commodity during the Middle Ages has since become cheaper and more commonplace. We can attribute that to the Industrial Revolution and its factories.”

Albert Schweitzer arrived in West Africa in April 1913. On average he saw thirty to forty people a day, most suffering from infections such as malaria. It took forty-one years before he saw an African patient with appendicitis—a regular occurrence in modern emergency rooms. Neither did he see cancer until the latter part of his time in Africa, when he treated an increasing number of cancer patients. Schweitzer suspected a connection as local people started living like their white visitors.

Weston A. Price, an American dentist, and his wife visited primitive populations around the world in the 1920s and 30s. They visited Australian aborigines, Polynesians, Eskimos, South and North American Indians, isolated villages in the Swiss mountains, and African tribes. The photos Price took are most revealing. The primitive populations had no dentists, no toothpaste or modern toothbrushes. “Despite this,” Eenfeldt observes, “they stood there smiling with bright white teeth that would make anyone in Hollywood jealous.” Price also sought out subsets of people living close to Western civilizations. Their photos were the complete opposite—broken teeth and terrible cavities. Eenfeldt’s conclusion: “If sugar and white flour can make your teeth rot, in what other ways can they harm the rest of your body?”

Thomas Latimer Cleave, born in 1906, became a doctor. He was hired by the British Navy, where he got to see diseases that occurred among different populations. Adding to his own observations, Cleave began asking other doctors for their experience with diseases. As Eenfeldt explains,

Cleave noted a long list of new diseases that had suddenly become prevalent around the world in a few decades. That could not be natural. He could only make one conclusion. Our bodies were not ill-designed, just improperly used. The diseases include obesity, diabetes, heart disease, gallstones, cavities, constipation, ulcers, and appendicitis.

He started publishing texts about his theory and summarized his research in The Saccharine Disease in 1974. Sugar and white flour were regarded as the cause behind all of the Western diseases.

Cleave was convinced that the issue was the purification and concentration of carbohydrates. It tricks us into eating more and can result in obesity over time. You don’t gain weight by being gluttonous or lazy. He noted how no wild animals become obese, regardless of the amount of food they have access to. Not when they keep their natural diet. The same should go for humans, but the problems arose with the new food.

Sir Richard Doll, one of the doctors who linked smoking with lung cancer, wrote one of the forewords for Cleave’s early books. Denis Burkitt, another renowned doctor, wrote the forward to The Saccharine Disease. Others agreed with Cleave. According to Eenfeldt, “At one point, things looked promising for Cleave’s theory. It could have changed the world.”

Another theory

What happened next, says Eenfeldt is a story “reminiscent of both a thriller and a catastrophe movie.” Eenfeldt paints the picture of the critical day:

“Sorry, it’s true. Cholesterol really is a killer. No fatty milk, No butter. No fatty meat.. .”

It is March 26, 1984, and the Americans were to be scared. They were to be scared of fat. The headline and the first sentence in a foreboding TIME magazine article leave no doubts. Neither does the cover (shown above), which featured a sad breakfast plate. The egg eyes and bacon mouth illustrate the sadness. The headlines say the rest: CHOLESTEROL—AND NOW THE BAD NEWS…

Strangely enough, the media was reporting on a pharmaceutical research report. A cholesterol-lowering drug had been found to reduce the risk of having a heart attack. After a couple of failed attempts, it was the first study to put forth a theory about the danger of fat. It was a popular theory on which many politicians, scientists, and lobbyists had bet their careers. Finally they had their chance. But were they right?

If one pill results in fewer heart attacks for risk patients, does that prove than lean cuisine can make Americans healthier?

The answer is, of course, no. The fear mongering was a long shot. No one could know what would happen. The politicians and scientists who supported the theory were probably under the impression that they were doing some good and that the end justified the means. With their conviction that fat was dangerous, they relaxed the requirement for scientific proof. When we look back, the conclusion is evident. The emperor had no clothes that day. Conviction cannot replace proof.

Rewind to 1958. Ancel Keys—the scientist on the 1961 TIME cover—thought he had the answer to heart disease in cholesterol. It needed to disappear.

Keys was a driven researcher who, according to Eenfeldt, sought the public spotlight. During World War II he designed the army’s rations, called K-rations. By the end of the war he had completed a study on starvation, using 36 conscientious objectors, who were starved during six months of meticulous monitoring. This research raised ethical questions about Keys’ research. But he persisted in his quest for recognition and it was his research on heart disease that earned him the name “Mr. Cholesterol” and the cover photo on TIME.

Eenfeldt goes into considerable detail about Keys’ research. During the 1950s Keys and his wife, a biochemist, traveled the world to gather data on the potential correlation between fat, cholesterol, and heart disease. Figure 1 shows what appears to show a solid correlation between deaths from heart disease and percentage of calories derived from fat in the populations of the six countries.

Figure 1

However, some years later, a skeptical colleague dug deeper into data from broader studies. Figure 2 shows how the larger data set of twenty-two countries was far less conclusive.

Figure 2

The correlation here is much weaker, hardly the near-perfect correlation of the 6-country data. As Eenfeldt states, “Keys had managed to choose exactly those countries that illustrated maximum correlation. . . . To simply pick out the statistics that fit one’s theory is a fatal scientific error. But the alleged forgery was not particularly well known, and Keys was not backing down.”

In 1958 Keys conducted a Seven Countries study that could have become the main pillar of the fear of fat. However, the data from the seven countries (Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Holland, Finland, Japan and the US), which was collected over an extended period, did not show a remote correlation between fat and heart disease. In Greece (the island of Crete), people ate a lot of fat, but had the fewest cases of heart disease. So, Keys changed his approach and focused on saturated fat. In itself, looking at another factor is the proper scientific approach, as long as it leads to a better explanation.

After a technical explanation of why saturated fat cannot be the culprit, Eenfeldt suggests how causality can be claimed where in fact there is no basis. To illustrate how far off the mark this can be, he uses a chart that seems to correlate municipal taxation with deaths caused by heart attacks—heart attacks increasing with higher tax rates. The chart would suggest that lowering taxes even more could eliminate heart attack deaths. Obviously, there has to be another explanation.

Or take the suggestion of a link between ice cream and drownings in Sweden. There may be a statistical correlation, but not a causal relationship. In fact, both ice cream consumption and drownings go up in the summer, but the real link—warm weather—produces the conditions to see an increase in both factors. In reality, the warm weather is not the cause of either ice cream consumption or drowning, but increases the opportunity for the real causes to produce their outcome.

Scientific method relies on well-crafted studies that are large enough to establish a control group and one or more test groups so that variables can be properly assessed. Eenfeldt calls these “intervention” studies. Good research further requires repetition of studies to see whether the reported conclusions are repeatable and the underlying assumptions valid. Only after extensive, multiple studies can a true consensus be reached, and if significant enough, a new paradigm (theory) adopted.

While the two theories—the ill effects of starch and sugar versus the fear of fat—were mirror images of each other, and despite problems with the latter theory, it moved into public acceptance. The theory of sugar and starch as the root of modern disease fell on hard times. Despite compelling data, it lacked advocates with the persuasive personality of Keys and for other reasons never reached the arena of public opinion. This opened the door for the fear of fat to win the day. “The problem was essentially very simple,” says Eenfeldt. “If fat was dangerous, carbohydrates had to be healthy. Otherwise there would be nothing with which to replace the fat.” Even soda, with all of its sugar could be called “low” or “no fat” to make it sound like a healthy alternative.

Enter the political arena. A committee led by Senator George McGovern had been focusing on the issue of malnutrition, but paused to review the problem of over-nutrition. In July 1976, after two days of testimony by experts, they wrote the first edition of The Diet of the United States. “When it came to fat, they predominantly relied on the experts that were convinced of the dangerous nature of fat, and the recommendation was to reduce one’s fat consumption.”

The recommendations, however, were controversial. The committee later published an updated version with more relaxed phrasing, but a similar low-fat theme. “A low-fat diet gradually became the norm,” while the scientific world was still in deep disagreement.” In the 1980s a series of studies were conducted, but according to Eenfeldt, failed to provide solid evidence of the link between dietary fat and heart disease. A sixth study tipped the scales, providing statistically significant numbers, but that study was testing a medication to reduce high cholesterol levels. “The conclusion was that a low-fat diet would produce the same cholesterol-reducing results. That was something the study had not even tested, something that every similar study has failed to this day.” But there was inertia behind the idea that there must be a link, so the public was receptive.

The paradigm shift to low-fat came in 1984 during an official “consensus conference.” According to Eenfeldt, “The board was comprised of people who were already convinced. Dissidents did not affect the conclusion. There were ‘no doubts,’ they said, that a low-fat diet would protect Americans older than two years against heart disease. . . . Stubborn dissidents were ostracized. . . . Skeptics were not favored.” To get federal funding for research (in the U.S.) required sticking to research fitting the low-fat theory.

A number of early critics saw holes in the theory, but it was the global epidemic of diabetes and obesity since 1984 that could not be denied. “Obesity has taken over in the United States in an unprecedented way. Now the epidemic is spreading across the Western world and beyond.”

Eenfeldt then describes the research in Sweden, including his own, that began to take seriously the problems with the low-fat approach, which had become widely accepted there. In discussing the impact, he uses a chart that shows the mirror-image relation of butter consumption and obesity (Figure 3).

Figure 3

The adoption of low-fat diets (replaced by high carbs dominated by starch and sugar) in the 1980s, led to the steady rise in obesity, illustrated here by data from Sweden. That shift in diet caused butter sales to plummet as people reduced saturated fats (by substituting highly processed carbs and switching to other “healthier” fats). As awareness that the Low-Fat Revolution was producing disastrous results, diet in Sweden began to back away from the low-fat approach around 2005. Butter sales began going back up, while obesity leveled off and has now started to decline.

Using a single factor, like butter sales, is illuminating, but needs to be seen as one of many factors. After all, if that farmer from the south of Sweden simply slathered his buckwheat porridge in butter, he would not be turning it into health food! A similar mixed message was illustrated in a recent news story that linked a shortage of butter in France to growing world-wide demand for croissants. In other words, the chart will only work when it represents a transition from a low-fat to a low-carb diet, which may then lead to switching from butter substitutes to the real thing.

Lessons to Apply

So, what can we learn from the low-fat paradigm shift that brought such widespread unintended consequences that it is now being questioned?

Scientific method must be followed and allowed to run its course. That means multiple studies or experiments over a long enough period of time to establish correlations and corroborate results. A problem in the low-fat paradigm shift was lowering the bar on the quality and quantity of research.